Nancy Reagan was initially told that Reagan wasn't shot outside the Hilton; but she went to George Washington Hospital as fast as she could anyway. When Nancy arrived, Michael Deaver (one of the members of Reagan's "Troika") told her that Reagan had been shot (the shooter was John Hinckley, Jr.). Reagan later said that he felt a blow in his upper back that was unbelievably painful, and initially thought he had a broken rib. When Reagan started coughing up blood, the Secret Service agent next to him ordered the limousine to the George Washington Hospital . . . during the few minutes to the George Washington, Reagan's condition worsened.

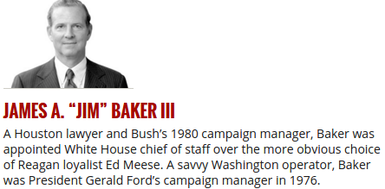

Baker, as Chief-of-Staff, had to decide whether-or-not to invoke the 25th Amendment; should Vice-President Bush be the acting-President while Reagan was undergoing surgery . . . Baker decided not to do so. Baker didn't want Bush to become an acting-President; Baker liked Bush very much, but Baker and the other Reagan loyalists didn't think Bush's conservative bona fides were nearly stout enough. Also, their was the fact that Baker and Bush were very good friends, and appearances mattered, even when the President was fighting for his life.

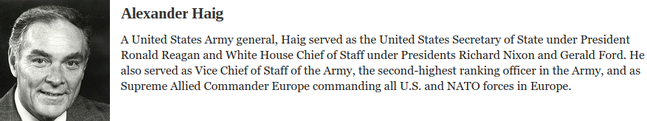

Haig was asked who was making decisions in the Executive Branch; Haig had intended to calm down the room (and nation), but he arrived out-of-breath, and his words had the opposite effect. Also, Haig made a mistake in terms of the line-of-succession according to the 25th Amendment; the Secretary of State was 5th, not 3rd, in the line-of-succession (after the President is the Vice-President, then the Speaker-of-the-House, then the President Pro-Tem of the Senate, THEN the SecState). Haig's "I am in control here" line was too easily used by TV to portray the SecState in the wrong manner; Haig's main intent was to let the USSR know that there were indeed people in charge of the government and the military. Haig regretted not composing himself before he took the podium and his choice of words . . . but he succeeded in pointing out that he was the senior Cabinet official present, and the government was functioning.

The rest of the surgery was straightforward, but still risky, in that an artery needed to be repaired, and a lung sutured (the surgery lasted 70 minutes on a President that was almost 70 years old). Reagan recovered, but Nancy never did; she would remain paranoid when her husband needed to leave the White House for any significant sojourn for the rest of his Presidency . . . Reagan was released after only thirteen days at George Washington Hospital.

Quigley claimed to have 30 March 1981 pegged as a "bad day" for Reagan; Nancy became addicted to contacting Quigely when Reagan resumed normal activities as President. Nancy involved Michael Deaver, who made sure that the astrologer remained secret; neither he or Nancy wanted to embarrass the President that she constantly used an astrologer to predict "good days" or "bad days" for her husband.

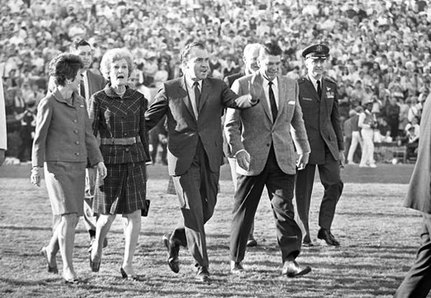

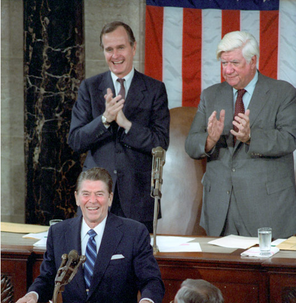

Soon enough during his address, Reagan launched into the topics of less federal spending, finding ways to reduce inflation and to lower taxes (pictured behind Reagan: VP Bush to the left, and Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill to the right).

Six months after his election, the economy was still in "Stagflation" mode; inflation had scarcely abated and interest rates were punishingly high; 8 million Americans were out of work, and real wages were down. Reagan stated that the effort to improve the economy started with the federal budget; in Reagan's view, government was too big and it spent far too much.

Reagan's proposed budget had moved along until House Democrats presented their version that kept social spending levels intact, raised taxes, and cut proposed increases in defense spending. Reagan responded that he proposed nothing more than to stop tax increases; he didn't advocate tax cuts as of yet. Reagan's address was in the aftermath of the first Space Shuttle Mission, which had just successfully concluded . . . Reagan stated that "we have much greatness before us"; the near-death experience from the attempted assassination only heightened Reagan's sense of mission as President