Story of Adventure, Heroism, and Treachery (2010)

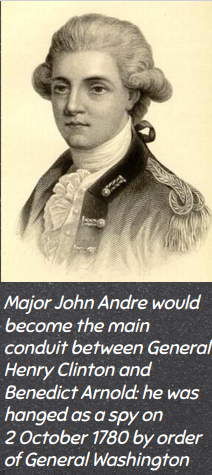

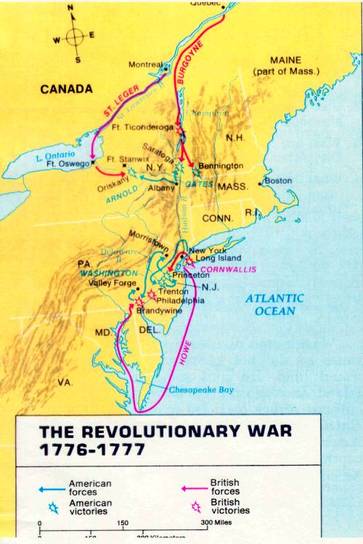

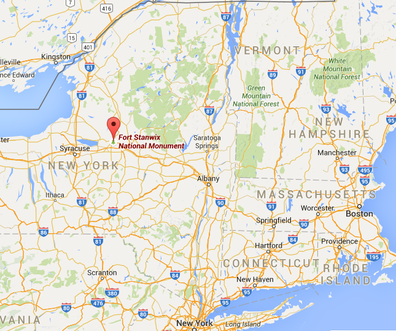

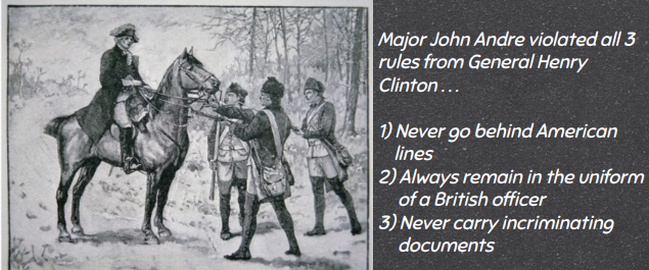

Arnold wrote a pass for Andre in order to get past any US soldiers; it was agreed that when Clinton saw the papers, the British attack at West Point would begin. If the timing was right, Clinton would get Fort Arnold, thousands of soldiers, and George Washington, who was en route to the fort. Andre couldn't leave until dark, and Joshua Hett Smith, who had been unwittingly assisting Arnold in his treason, would ride with him and show Andre to the British line. Smith agreed, but wanted to know why Arnold was in a British uniform, to which Arnold basically shrugged off his question.

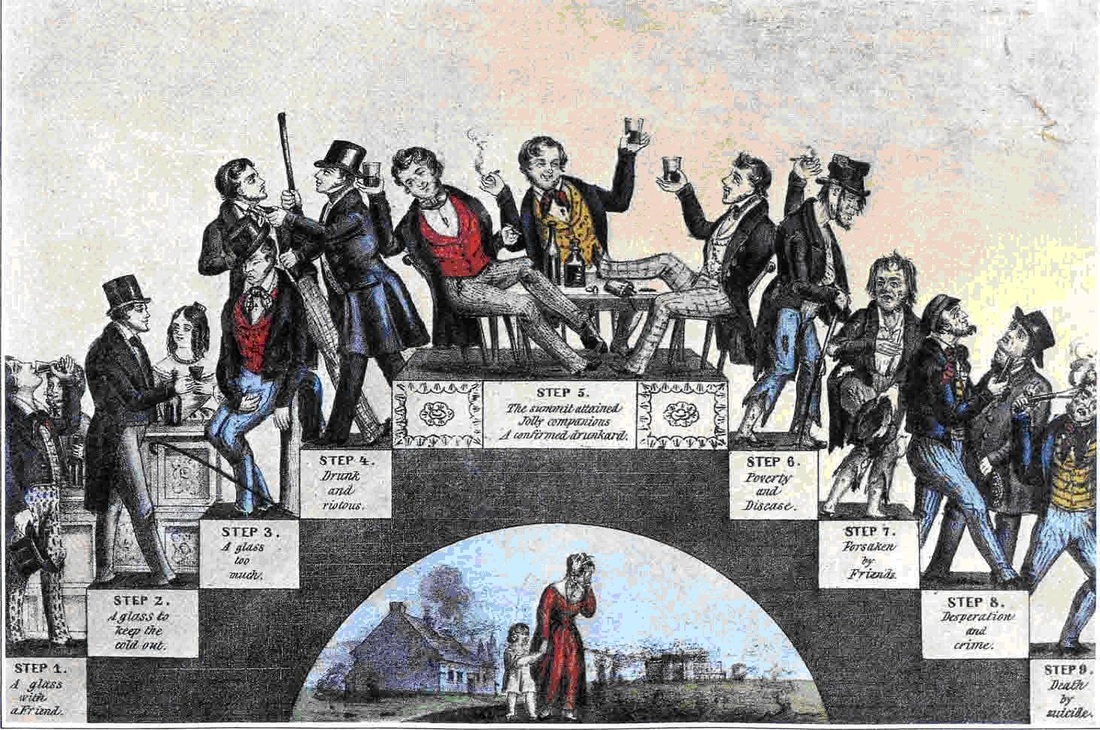

Smith loaned Andre civilian clothes, and Arnold went back to his wife, Peggy. For Arnold and Andre, there had been some unfortunate glitches in their plan so far, but their plan and timing was still intact. When Andre put on Smith's civilian clothes in Smith's house, he violated the last of Clinton's rules, which was to all times remain in uniform. As Smith and Andre rode out from West Point, Smith chatted endlessly, while Andre kept quiet, not doubt trying to think about how to get out of his dangerous situation.

Smith and Andre spent the night in a farmer's house, but Andre wasn't able to sleep, since he was still shaken from the day's events, which included passing on the road an American, Colonel Webb, who had been a prisoner in New York City when Andre was stationed in the city. . . Webb showed no signs of recognizing Andre. In the morning, Andre loosened up with Smith, but after breakfast at the farm house Smith told Andre he didn't want to ride into

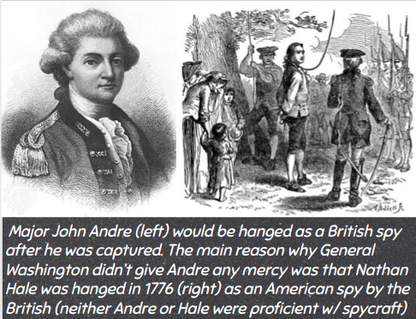

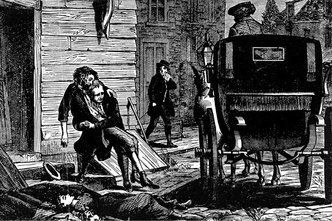

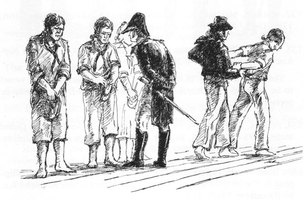

No-Man's Land. Smith gave Andre directions, and then Smith (and his slave) rode off in the opposite direction. Andre continued alone. A few miles ahead in Tarrytown, three men were crouched by the side of the road, probably a mix of "Skinners" and American militiamen. The three men decided to stop the coming rider if they didn't know him . . . that rider was Major Andre.

The three men had found the documents given to Andre by Arnold; Andre denied he was a spy and demanded to be set free. The three men asked Andre what his freedom was worth, to which Andre in effect replied "any sum you want". That sum was 100 guineas, his horse, saddle, bridle, and his fancy watch. Andre actually haggled with the three men until Andre offered the ridiculous sum of 10,000 guineas. The three men decided it was too risky collecting money from a British officer/spy . . . it was surely safer to turn in Andre to the American side, since he sure seemed to be worth something. At that point, Andre knew his chances at returning to the HMS Vulture and New York City were nil.

Meanwhile, Smith told Arnold that Andre was safely on his way to New York City. At the same time, aboard the HMS Vulture, the crew was nervous, in that they were still waiting for Andre's return. Andre was delivered to an American army post that was commanded by Colonel John Jameson, who was unsure what to do with Andre.

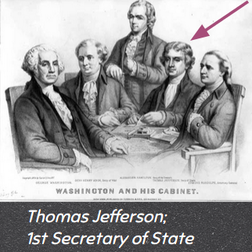

Washington's headquarters were located close-by, and the messenger actually passed the camp. He turned around and found the camp, but Washington wasn't there, because the general was studying the land, river, and fort very near West Point. Washington wasn't in any particular hurry to reach Arnold, despite being expected for breakfast . . . General Lafayette was getting nervous, advising Washington that they needed to go see Arnold . . . but the rider that was still trying to locate Washington was probably more nervous than Lafayette.

Washington decided to send two officers ahead to let Arnold know they would be late to breakfast. Those officers were with Arnold when Jameson's other rider delivered the message. One of Washington's officers noticed Arnold's reaction to reading the note; he seemed embarrassed and agitated . . . but why? Arnold now knew that Andre had been captured, and that Washington had the documents . . . and that Washington would be there any minute. Arnold didn't know if Washington was actually in possession of the papers yet, and he didn't want to wait to find out.

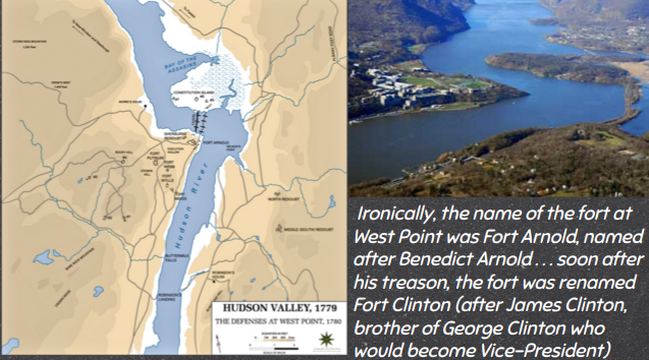

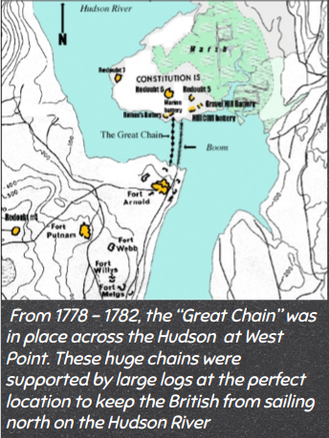

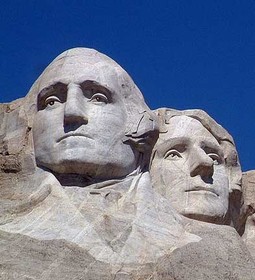

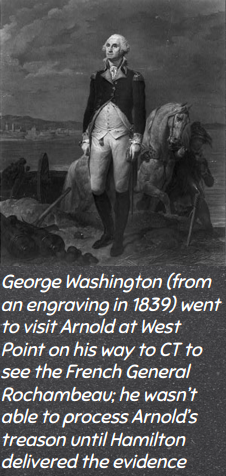

Just minutes after Arnold left, Washington arrived. Washington was told that Arnold was at West Point, so after a quick breakfast, Washington and his entourage rowed across the Hudson to Fort Arnold, expecting a formal greeting, which included a 13 cannon salute. However, there was nothing of the sort, and Washington soon discovered that Arnold hadn't been on that side of the river at all that day. Washington didn't have any idea why things weren't normal; the fort looked neglected and soldiers were not in their proper places . . . the strategic location was wide open for an attack.

Finally, Colonel Jameson's other messenger found Washington, and handed the general the message and the documents. Shortly after starting to read the papers, Washington's hands started shaking; he knew immediately that Arnold had betrayed him, saying "who can we trust now"? Arnold was out of Washington's reach (after an exhaustive search), so Washington focused on preparing West Point for an attack, placing General Nathaniel Greene in charge.

Peggy heard Washington's voice, and asked to see him upstairs. When Washington entered the room, Peggy again started raving, claiming to not recognize Washington, accusing him of murdering her child. Washington tried to comfort Mrs. Arnold, but it wasn't his strong suit. Lt. Colonel Alexander Hamilton was in the room as well, and he saw the sweetness of beauty and innocence mixed with lost senses. Peggy was acting, but again, she was truly afraid. Peggy needed to convince Washington that she had no part in Arnold's treason, and she succeeded . . . after Washington left her room, she lay calmly down on the bed, plotting her next series of decisions.

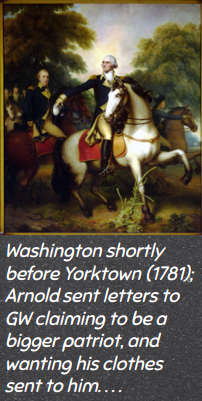

Washington and the men stationed at West Point stayed up all night for a British attack that never came; Washington was still shaken by the recent shocking turn of events. Arnold wrote Washington from the HMS Vulture; true to form, Arnold thought that he had acted correctly. Arnold did one decent thing in his series of letters to Washington, in that he absolved all those around him of being a part of his actions. The HMS Vulture sailed back to New York City, where Arnold walked the streets in the uniform of a British general.

Arnold didn't get the reception he was expecting; most just stared icily at him. Arnold's arrival stunned the residents of New York City; when the shock wore off, many started to wonder about Major John Andre. General Clinton was a wreck over Andre, and he didn't welcome Arnold, which meant the officers that ranked below Clinton followed suit. Arnold walked the streets of New York City in his new uniform, more alone than he had ever been. Arnold's plot had failed, and if Andre died, the catastrophe would be complete.