Source: H.W. Brands. Reagan: The Life (2015)

Republican conservatives absolutely hated the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan, mostly for fiscal reasons; to them, the New Deal had gone international, and Big Government was growing bigger at the expense of the American citizens. The Election of 1948 looked bleak for President Harry Truman, since many Americans were clamoring for a change-of-party after 16 years of Democrats in the White House. But Truman barely eaked-out a victory; Ronald Reagan, out of habit, remained loyal to the Democrats, endorsing Truman and raising campaign funds for the President.

Truman celebrated his narrow electoral victory by having the US join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which was a huge affront to Republican conservatives. NATO was America's first peace-time alliance, which committed the US in advance to defend Britain, France, Italy, and 8 other nations from any external attack. Truman and most of the Democrats saw NATO as the "Capstone of Containment", while conservatives thought war-making powers were taken from Congress and handed to the Executive.

Republicans overall were in a quandary, in that they hated Big Government, but they also hated Communism. In the end, Republicans (especially conservatives) believed that the threat to US liberty was greater from international communism than from domestic liberals. Therefore, there was just enough Republican support in Congress to approve NATO, as well as Truman's Cold War agenda.

Truman celebrated his narrow electoral victory by having the US join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which was a huge affront to Republican conservatives. NATO was America's first peace-time alliance, which committed the US in advance to defend Britain, France, Italy, and 8 other nations from any external attack. Truman and most of the Democrats saw NATO as the "Capstone of Containment", while conservatives thought war-making powers were taken from Congress and handed to the Executive.

Republicans overall were in a quandary, in that they hated Big Government, but they also hated Communism. In the end, Republicans (especially conservatives) believed that the threat to US liberty was greater from international communism than from domestic liberals. Therefore, there was just enough Republican support in Congress to approve NATO, as well as Truman's Cold War agenda.

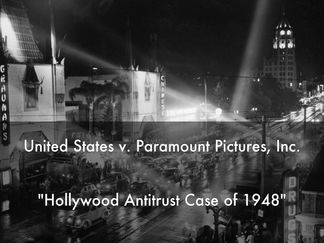

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that the major studios couldn't also control theater distribution (U.S. v. Paramount); for the first time, the studios had to compete to place their movies in American theaters. The big movie stars had nothing to worry about, but marginal actors, such as Ronald Reagan, found less-and-less work.

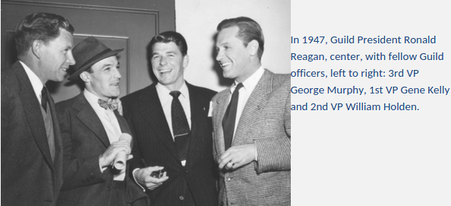

Another factor that changed the landscape for the big studios in Hollywood was television. By 1955, 30 million homes had a TV, which was about half the residences in America (by 1960, there would be 60 million residences with TV). As the President of the Screen Actor's Guild (SAG), Reagan had to decide if TV actors would be represented by SAG. To Reagan and SAG, TV actors seemed more like stage actors, so the decision was delayed. The radio industry tried to create an all-encompassing union for actors & performers, but Reagan still resisted, believing that movie actors represented the elite aspects of the industry. Plus, most of the members of SAG lived in Hollywood, where most other performers lived in New York City.

Another factor that changed the landscape for the big studios in Hollywood was television. By 1955, 30 million homes had a TV, which was about half the residences in America (by 1960, there would be 60 million residences with TV). As the President of the Screen Actor's Guild (SAG), Reagan had to decide if TV actors would be represented by SAG. To Reagan and SAG, TV actors seemed more like stage actors, so the decision was delayed. The radio industry tried to create an all-encompassing union for actors & performers, but Reagan still resisted, believing that movie actors represented the elite aspects of the industry. Plus, most of the members of SAG lived in Hollywood, where most other performers lived in New York City.

Reagan also saw a political problem, believing the Television Authority (TVA) might be a haven for subversives (Reagan characterized the TVA as "catnip to a kitten where the little Red brothers are concerned"). In other words, Reagan believed that "One Big Union" played into the hands of communist subversives; ultimately, SAG stood pat, and TV actors joined the radio performers in the American Federation of TV & Radio Artists.

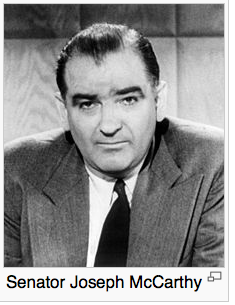

Theodore Roosevelt was the first celebrity President, using the newspapers as his medium to do so. Franklin Roosevelt was the first President to really use the radio, and Reagan, as President, would use TV to great effect, but . . . it was Senator Joseph McCarthy (R; WI) that was the first major politician to use television. The political atmosphere in America was perfect for an ambitious politician like McCarthy; in 1949, the USSR announced they had the atomic bomb, Klaus Fuchs and Julius & Ethel Rosenberg were arrested, and China became a communist nation. The political atmosphere was perfect for McCarthy's rise to prominence when he gave his "Communist Infiltration" televised press conference; to most Americans, there was a real battle between Democracy and Communism, not only globally, but also in the U.S.

Theodore Roosevelt was the first celebrity President, using the newspapers as his medium to do so. Franklin Roosevelt was the first President to really use the radio, and Reagan, as President, would use TV to great effect, but . . . it was Senator Joseph McCarthy (R; WI) that was the first major politician to use television. The political atmosphere in America was perfect for an ambitious politician like McCarthy; in 1949, the USSR announced they had the atomic bomb, Klaus Fuchs and Julius & Ethel Rosenberg were arrested, and China became a communist nation. The political atmosphere was perfect for McCarthy's rise to prominence when he gave his "Communist Infiltration" televised press conference; to most Americans, there was a real battle between Democracy and Communism, not only globally, but also in the U.S.

Not long after McCarthy's televised press conference, North Korea invaded South Korea. McCarthy's "discovery" of communists in the State Department gave Republicans a powerful weapon, which they used against President Truman and the Democrats. Stunned by Truman's victory in 1948, the Republicans abandoned all respect for the President, and declared war on all-things-Truman. To the Republican leadership, McCarthy was just the bashi-bazouk ("undisciplined bandit") to lead their charge.

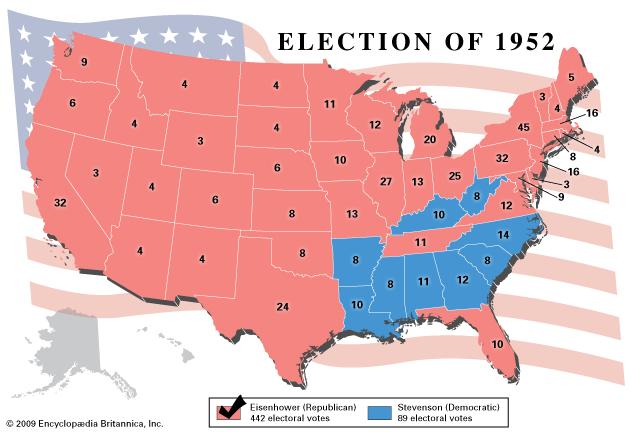

McCarthy's attacks on Truman made the President un-electable in 1952; Truman didn't even pursue the Democratic nomination. Dwight Eisenhower delivered the White House to the Republicans for the first time since Herbert Hoover in 1928. McCarthy soon attacked Ike, claiming that he wasn't nearly as vigilant as he needed to be as President in dealing with the USSR, as well as subversives in the U.S. The Republican Leadership in the Senate gave McCarthy the chair on the Committee of Government Operations, and he used that chairmanship as a platform for his holy war against subversives, using live television to cover his committee hearings.

McCarthy's attacks on Truman made the President un-electable in 1952; Truman didn't even pursue the Democratic nomination. Dwight Eisenhower delivered the White House to the Republicans for the first time since Herbert Hoover in 1928. McCarthy soon attacked Ike, claiming that he wasn't nearly as vigilant as he needed to be as President in dealing with the USSR, as well as subversives in the U.S. The Republican Leadership in the Senate gave McCarthy the chair on the Committee of Government Operations, and he used that chairmanship as a platform for his holy war against subversives, using live television to cover his committee hearings.

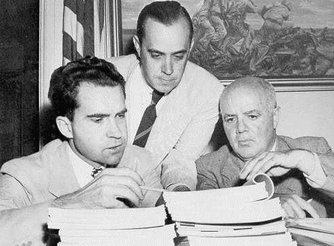

The Army-McCarthy Hearings aired on live television in 1954, with ABC showing all of the hearings, while CBS and NBC had partial coverage. President Eisenhower and the Army were still seething at McCarthy's attacks on SecState George Marshall, and Ike and the Army set a trap for McCarthy.

A McCarthy aide wanted favorable treatment for an assistant that had been drafted, which allowed the Army leadership to publicly denounce McCarthy . . . in essence, the Army "triple-dog-dared" McCarthy to hold televised hearings, and McCarthy obliged. The hearings aired for 36 days with 20 million viewers; McCarthy lacked the requisite "TV Persona", and as a result his approval plummeted. McCarthy's defeat proved the power of television to shape political perceptions; among many others, John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan were watching, learning, and waiting. (Below: the moment caught on television that was the beginning-of-the-end for Senator Joseph McCarthy . . . "Have you no sense of

decency, sir . . .")

A McCarthy aide wanted favorable treatment for an assistant that had been drafted, which allowed the Army leadership to publicly denounce McCarthy . . . in essence, the Army "triple-dog-dared" McCarthy to hold televised hearings, and McCarthy obliged. The hearings aired for 36 days with 20 million viewers; McCarthy lacked the requisite "TV Persona", and as a result his approval plummeted. McCarthy's defeat proved the power of television to shape political perceptions; among many others, John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan were watching, learning, and waiting. (Below: the moment caught on television that was the beginning-of-the-end for Senator Joseph McCarthy . . . "Have you no sense of

decency, sir . . .")