The Last Great Battle of the American West (2009).

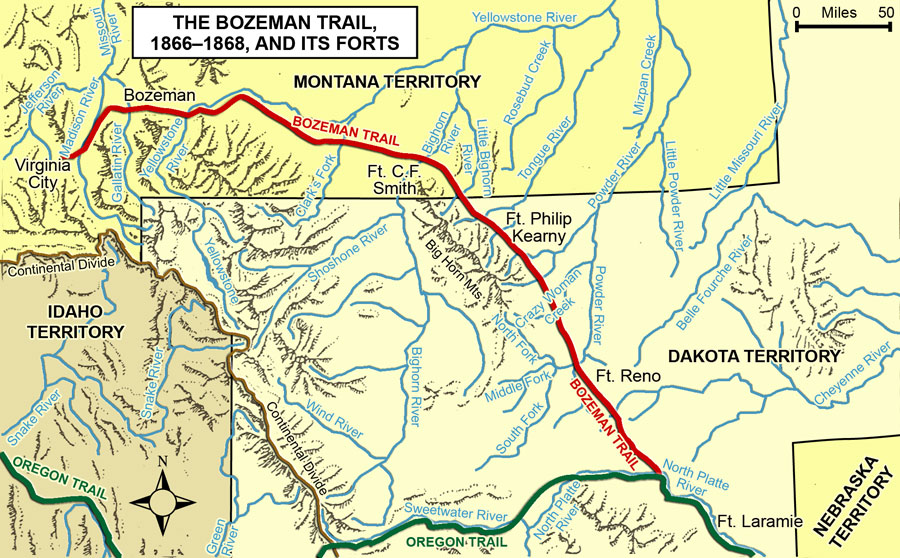

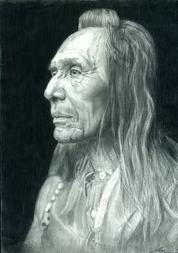

Fetterman had (supposedly) loudly boasted that he could defeat any number of Native warriors with only 80 men; he and all of his men were killed by the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors (to the U.S. Government, it was known as the Fetterman Massacre). Crazy Horse (Oglala Lakota) was the war chief that led Fetterman into the lethal trap; Crazy Horse's reputation as a warrior was so secure, he would drop back and let other warriors count coup.

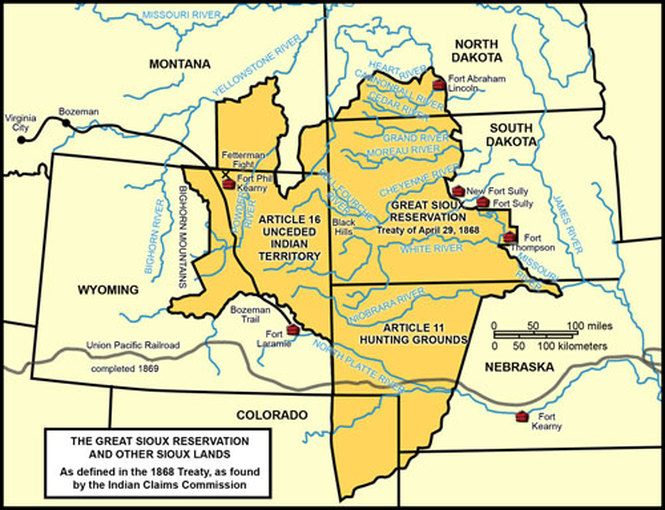

The treaty stated that Natives could follow the buffalo if the animals were in such numbers to justify pursuit, but they couldn't occupy lands outside of the reservation area (General Sherman was advised that the buffalo wouldn't be in great numbers very much longer). The treaty even allowed the U.S. Government to build a railroad through the reservation to the Pacific Ocean. In only a few months after the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was signed, Sherman (largely on his own initiative) declared that any Natives that located outside of a reservation should be declared "hostile".

The War Department disagreed with the President; the "kind treatment" was mostly followed on reservations, but they viewed "hostiles" in an entirely different light. The War Dept. assumed that the strategies and tactics used in the Southern Plains would translate to success in the Northern Plains . . . it would not turn out to be the case.

In 1871, a Congressional squabble led to legislation that actually forbid ratifying treaties with Natives. As a result, Grant used Executive Agreements as a substitute for negotiating treaties, and those Executive Agreements were then ratified by Congress. These agreements were treaties by another name (everyone involved understood), but ironically, the House of Representatives had more input with the actual negotiations under Grant's strategy.

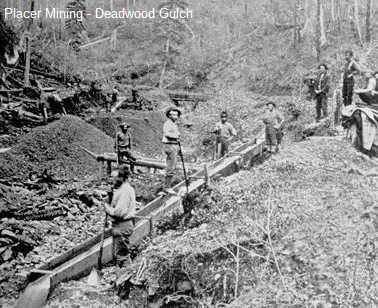

The fuse to the Northern Plains powder keg was lit in the Black Hills region. Knowledge of gold in the Black Hills dated back to the early-1850s, but after the Panic of 1873 ushered in the worst economic depression in U.S. History (to that point), many men traveled to the region. This search for gold by these desperate men in the Black Hills would be backed-up by the presence of U.S. soldiers.

In short order, over 10,000 gold mines were established in the Black Hills; there were too many rushing to the region for the Government to keep out illegal squatters; to the Lakota, all the whites in the Black Hills were illegal squatters. By tradition and treaty, the Black Hills belonged to the Lakota. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail made it clear that they (and other prominent chiefs) would not sell the region to the U.S. . . . Red Cloud and Spotted Tail were "summoned" to Washington, D.C. to negotiate terms for selling the land, but they adamantly refused to sign.

The U.S. Government then sent a commission to the Black Hills region to try and purchase the land, and over 5000 Lakotas met with them in Nebraska. The non-treaty faction of the Lakotas, led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, stated that the Black Hills would be defended to the death. The commission barely escaped the area with their lives, and returned to Washington, D.C. in high dudgeon.

(pictured). After the meeting, Grant decided (it's more likely that he was convinced) to claim that the Sioux abrogated (broke) the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

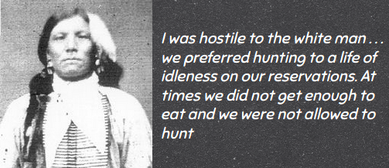

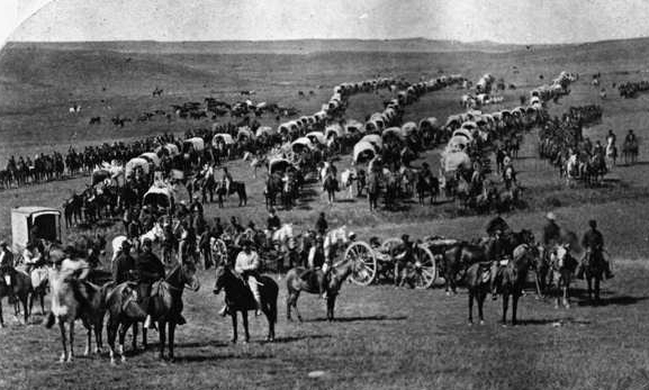

The U.S. Army had been waiting for any excuse to have all-out war in the Northern Plains against the "hostiles"; now the Army's hands had largely become untied . . . all that was needed was the requisite ultimatum. Generals Sherman and Sheridan ordered that any Natives that were not in a U.S. Government reservation by 31 January, 1876, would be officially classified as "hostile" to the U.S. Government. The timing and seasonal conditions made the deadline a practical impossibility to meet in any regard, and most (potentially "hostile") Lakotas (and other Natives) had no intention of going to a reservation anyway . . . so the deadline passed, and Natives outside of a reservation became classified as "hostile".

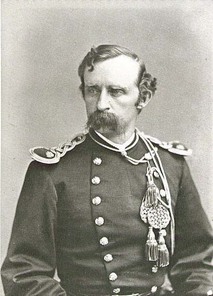

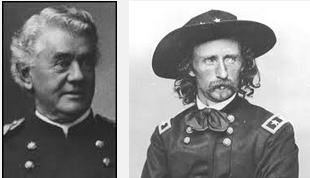

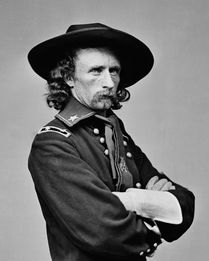

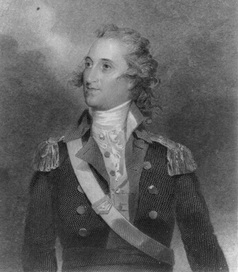

In opposition to these superb guerilla fighters, Sheridan could only muster 3000 soldiers in the Departments of the Dakota and the Platte. These soldiers were ill-equipped, poorly motivated, and most were malingerers, criminals, worthless "bounty jumpers" (those paid to join the army, and then ran away) . . . basically the scum of American society. To command this riff-raff, Sheridan called on a handful of Civil War officers that were vying for the few top-ranking positions in the shrunken post-Civil War Army. Among them were George Crook, Nelson Miles, John Pope, John Gibbon, Eugene Carr, Wesley Merritt, Ranald S. Mackenzie, and Sheridan's favorite attack dog, George Armstrong Custer (pictured, 1876).