Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent (2009)

On 3 August 1846, Polk received confirmation of Santa Anna's desire to return to Mexico; if current negotiations with the Mexican government failed, then Santa Anna was Polk's "Insurance Policy". From the very beginning of the war with Mexico, Polk pursued a negotiated peace while prosecuting an aggressive war. Polk, the Political Chess Master, was setting up his pieces on the board of statecraft . . . but by the Summer of 1846, Polk could no longer hide, or deny, his overall strategy of territorial expansion.

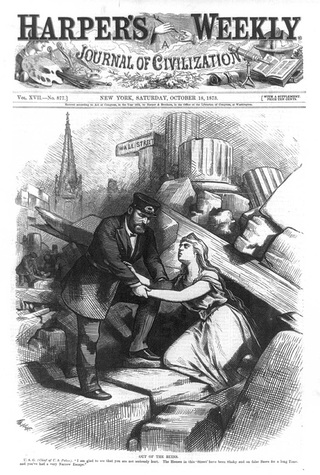

But in the House of Representatives, Polk was unable to keep the progress of the $2m Bill secret, and he was forced to write an Open Message to Congress explaining the purpose of the bill. Almost immediately, House Whigs announced their opposition to the bill; in their view, Polk was trying to avoid responsibility for a war he started. Interestingly, one of Polk's goals with the Open Letter was to put the onus on the House if the $2m Bill failed. It was during the House debate on the $2m Bill that a first-term Representative, David Wilmot (D; PA), appeared on the historical stage. His motive for what became known as the Wilmot Proviso was most likely to make a name for himself in the House by intensifying the debate on the $2m Bill.

Wilmot decided to introduce what he overheard from the "Barnburners" on the House floor in order to make the idea his own, for the record at least. Wilmot had never shown this kind of defiance against Democrats loyal to Polk, and it was rather surprising, in that Wilmot was not an opponent of the war, he wasn't an Abolitionist, he did not view African slavery as immoral, and he wasn't against slavery's expansion in the West. If Wilmot was passionate about anything, it was promoting the expansion of Free Labor.

Immediately, the war debate changed - the Mexican War and the expansion of slavery were now intertwined. It was immaterial if the potential territories did not have any interest in slavery . . . Senator Thomas Hart Benton (D; MO) commented that "never were two parties so completely at loggerheads over nothing". Polk was outraged, referring to Wilmot's Proviso as "a mischievous and foolish amendment"; to Polk, the war had zero connection with slavery.

The Speaker of the House, John Wesley Davis (D; IN) who wanted to be absolutely sure the $2m Bill passed with the Wilmot Proviso attached, delayed and obstructed proceedings to the brink of midnight when the session was over, blocking any efforts of those in opposition to the Proviso to make an official motion. However, Davis forgot that the clock in the House ran 8 minutes faster than the clock in the Senate, and he foiled his own efforts at getting the bill with the Wilmot Proviso sent to the Upper Chamber in the last few minutes for a quick vote . . . whoops. The House ended its session with the Wilmot Proviso attached to the $2m Bill, and the Senate was not able to vote on the bill because the session of Congress had ended . . . for now, Polk's $2m Bill was dead, as was his leverage in Congress concerning the war with Mexico.

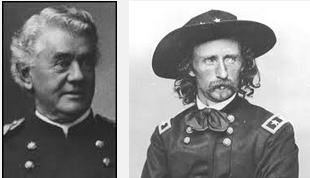

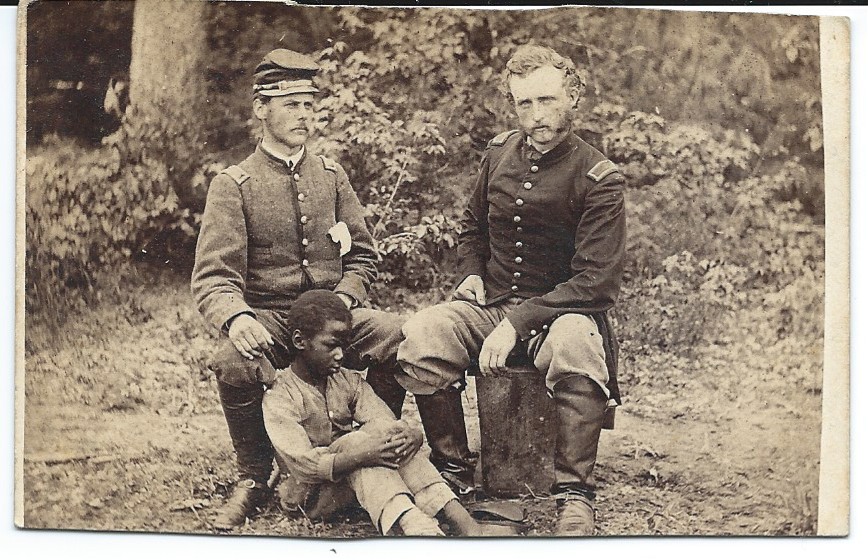

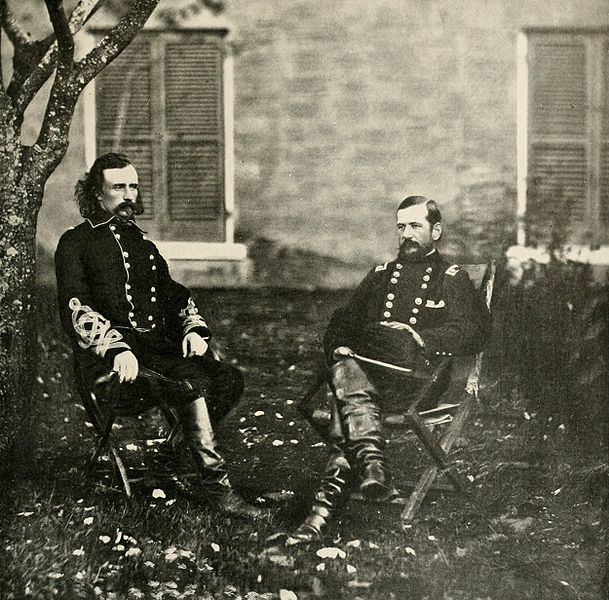

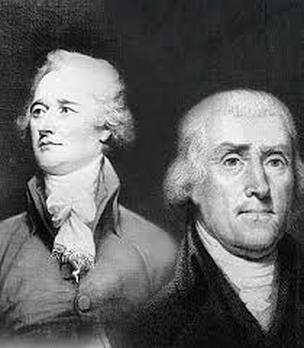

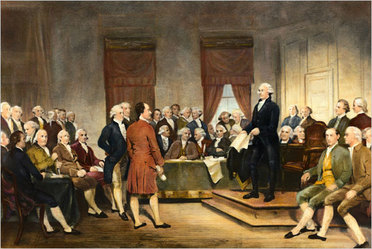

Even with the defeat of the $2m Bill, Polk had been the most productive legislative President in US History to that point. He had finalized the annexation of Texas, was very close to ending the Oregon dispute with Great Britain, introduced much-needed tariff reform, and created an Independent Treasury, all in one legislative session. And, he started a war with Mexico, which to Polk's point-of-view, was absolutely necessary in order to expand America's border to the Pacific. Polk (pictured left) had done more in his first 18 months as President than even his mentor, Andrew Jackson (pictured right), had accomplished in 8 years.