Source: Ron Chernow. Washington: A Life (2010)

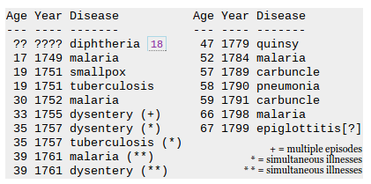

President George Washington, as a Virginia Planter, found it hard to adjust to a sedentary job in an urban setting; it very may well have weakened his overall health (pictured: a list of GW's serious health problems). In June, 1789, a fast-growing tumor appeared on his left thigh, accompanied by a high fever. It became excruciating for GW to even sit down - as it turned out, GW was in mortal danger of dying. He most likely had a carbuncle, which was a cluster of boils connected to each other under the skin.

On 17 June, 1789, Dr. Samuel Bard operated on GW's left thigh. The tumor was very large, and Bard had to excise the infected tissue and pus. It was an enormously painful procedure, but GW remained unfailingly courteous. GW was bedridden for weeks, and many wondered if he would ever regain the strength necessary to lead the nation as its first President. By early September, GW told Dr. Bard that the inflammation was almost gone.

On 17 June, 1789, Dr. Samuel Bard operated on GW's left thigh. The tumor was very large, and Bard had to excise the infected tissue and pus. It was an enormously painful procedure, but GW remained unfailingly courteous. GW was bedridden for weeks, and many wondered if he would ever regain the strength necessary to lead the nation as its first President. By early September, GW told Dr. Bard that the inflammation was almost gone.

In June, 1789, Congress tried to pass a law that required GW to get the permission of the Senate if he wanted to remove a member from his Cabinet. The Senate vote was a tie, and Vice-President John Adams voted against the bill. The significance of VP Adams' vote was that it prevented the emergence of a Parliamentary-style Democracy in the U.S.

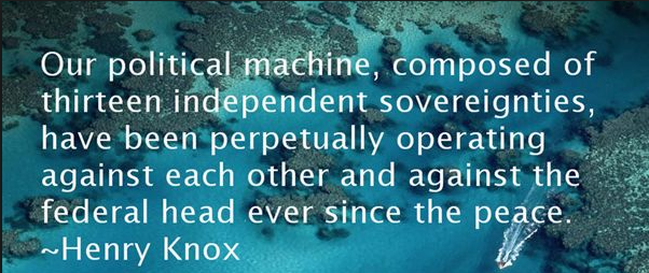

President Washington appeared in the Senate twice. The first was to personally ask why one of his appointments was being blocked. The second (and last) time was to inquire (with his Secretary of War, Henry Knox) the status in terms of ratification of a negotiated treaty with the Creek Nation. The Senate obfuscated by referring the proposed treaty to a committee for further study; GW responded by saying "that defeats the whole purpose of my coming here" - Washington never again returned to the U.S. Senate.

From that point on, President Washington sent missives to Congress, notifying them of his decisions. These actions did more to define the Presidency and the conduct of foreign policy than an entire shelf of Supreme Court decisions on the separation of power among the three branches.

(Below: From the 15:12 - 18:57 mark, watch GW in the Senate w/ the Creek Treaty)

President Washington appeared in the Senate twice. The first was to personally ask why one of his appointments was being blocked. The second (and last) time was to inquire (with his Secretary of War, Henry Knox) the status in terms of ratification of a negotiated treaty with the Creek Nation. The Senate obfuscated by referring the proposed treaty to a committee for further study; GW responded by saying "that defeats the whole purpose of my coming here" - Washington never again returned to the U.S. Senate.

From that point on, President Washington sent missives to Congress, notifying them of his decisions. These actions did more to define the Presidency and the conduct of foreign policy than an entire shelf of Supreme Court decisions on the separation of power among the three branches.

(Below: From the 15:12 - 18:57 mark, watch GW in the Senate w/ the Creek Treaty)

President Washington made the Executive the principle actor in the federal government, negotiating treaties and nominating people for confirmation. GW knew that one man could make and take decisive action, as opposed to a legislative body. Among his decisive actions, and an enduring mystery of GW's Presidency: why did he relegate Vice-President John Adams (pictured) to a minor role in his administration . . . Adams was clearly excluded from Washington's inner circle of advisors.

Adams was probably a casualty of being identified, by Washington, as the nominal head of the Senate. GW also had a long memory of those that criticized him during the Revolution, and Adams was one of the names at the top of Washington's list. GW believed that criticism was a lack of loyalty, and many people paid a price for what they said about Commander-in-Chief Washington when he was President. Meanwhile, Adams was secretly exasperated by GW's success and prestige as President; John Adams' greatest fear was that Washington and Franklin would dwarf him in American History.

Adams was probably a casualty of being identified, by Washington, as the nominal head of the Senate. GW also had a long memory of those that criticized him during the Revolution, and Adams was one of the names at the top of Washington's list. GW believed that criticism was a lack of loyalty, and many people paid a price for what they said about Commander-in-Chief Washington when he was President. Meanwhile, Adams was secretly exasperated by GW's success and prestige as President; John Adams' greatest fear was that Washington and Franklin would dwarf him in American History.

What hurt Adams was that Washington preferred to tap the talents of younger men, such as Hamilton, Madison, and Jefferson. What hurt Washington's focus in his early months as President was that he was absolutely besieged with office seekers, since he had to fill over 1000 posts in the new federal government. GW tried to be as impartial as possible with his selections because he wanted to strengthen the legitimacy of the new government.

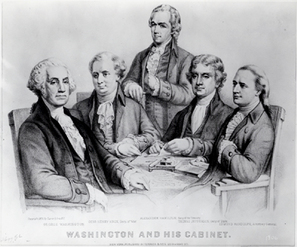

Washington set up five departments that were designed to provide advice: Treasury, War, State, Attorney General, and Postmaster General. With the Constitution mum about Presidential advisors, GW created the first Cabinet (not pictured; the Postmaster General, Samuel Osgood); by doing so, he created a major shift from Legislative to Executive (in effect, he found another way to bypass Congress). Jefferson viewed the first Cabinet as a wheel, with Washington as the hub, and the others as the spokes . . . but those spokes featured an incredible array of talented young (relative to GW) men.

Washington set up five departments that were designed to provide advice: Treasury, War, State, Attorney General, and Postmaster General. With the Constitution mum about Presidential advisors, GW created the first Cabinet (not pictured; the Postmaster General, Samuel Osgood); by doing so, he created a major shift from Legislative to Executive (in effect, he found another way to bypass Congress). Jefferson viewed the first Cabinet as a wheel, with Washington as the hub, and the others as the spokes . . . but those spokes featured an incredible array of talented young (relative to GW) men.

SecWar Henry Knox was Washington's closest friend (kind of his "Work-Wife") and ally, which he desperately needed, since he wasn't really close to anyone else but his wife Martha. Typically, GW wasn't an original thinker or policy-maker, but he was very comfortable helping Knox supervise the War Department. For the Treasury, GW first approached Robert Morris, but he felt he was too busy (and also didn't want to mess w/ his prosperity), so he recommended Alexander Hamilton (pictured left below with Jefferson). GW knew Hamilton's faults, but he had worked with him twice before during the Revolution and the Constitutional Convention. It's hard to believe, but Hamilton, the great Secretary of the Treasury, wasn't Washington's first choice for the position.

For the crucial position of Secretary of State, GW offered the post first to John Jay, but Jay had his eye on being the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. GW then "settled" for someone he knew from his days in the Virginia Assembly: Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson took months to decide whether-or-not to accept the position; he took so long that both GW and James Madison had to pressure him hasten his decision (to accept!).

Hamilton practically burst through the doors of the Treasury Department with sky-high enthusiasm and a desire to do his best to make the new federal government a long-term success. Jefferson, on the other hand, was not very enthusiastic in carrying out his duties as the first SecState. A possible reason for his delay for accepting the post, and his lack of energy in heading State was that he wasn't very comfortable with the federal government as envisioned, written, and ratified.

For the crucial position of Secretary of State, GW offered the post first to John Jay, but Jay had his eye on being the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. GW then "settled" for someone he knew from his days in the Virginia Assembly: Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson took months to decide whether-or-not to accept the position; he took so long that both GW and James Madison had to pressure him hasten his decision (to accept!).

Hamilton practically burst through the doors of the Treasury Department with sky-high enthusiasm and a desire to do his best to make the new federal government a long-term success. Jefferson, on the other hand, was not very enthusiastic in carrying out his duties as the first SecState. A possible reason for his delay for accepting the post, and his lack of energy in heading State was that he wasn't very comfortable with the federal government as envisioned, written, and ratified.

A main source for the problems and friction between Hamilton and Jefferson was that GW wanted his Cabinet to advise him on all fronts. For example, GW would often ask Hamilton for input on foreign affairs, which obviously rankled Jefferson. It also meant that Cabinent members often tread on each other's turf, and rivalries and resentment were the consequence.

The Attorney General was Edmund Randolph (pictured; he was only 36), and he was frustrated in that he really didn't have a department to run like the others . . . it was basically GW and him. Randolph had so little to do that he actually took private clients as a lawyer.

There was high turnover in the early years of the Supreme Court under the Constitution; "Riding the Circuit" was the main reason. Supreme Court justices spent a long time away from the comforts of home, and also had to endure miserable working conditions and substandard lodging. The lack of prestige alone lead to resignations and a low-level of interest in serving on the Court. GW would appoint 11 justices to the Supreme Court (in the early decades, there were only 6 justices) . . . the Supreme Court was an institution searching for a mission.

The Attorney General was Edmund Randolph (pictured; he was only 36), and he was frustrated in that he really didn't have a department to run like the others . . . it was basically GW and him. Randolph had so little to do that he actually took private clients as a lawyer.

There was high turnover in the early years of the Supreme Court under the Constitution; "Riding the Circuit" was the main reason. Supreme Court justices spent a long time away from the comforts of home, and also had to endure miserable working conditions and substandard lodging. The lack of prestige alone lead to resignations and a low-level of interest in serving on the Court. GW would appoint 11 justices to the Supreme Court (in the early decades, there were only 6 justices) . . . the Supreme Court was an institution searching for a mission.

For Washington, the good news about being President was, unlike being Commander-in-Chief during the Revolutionary War, he was able to take his time in making most every decision. Washington, therefore, made far-fewer mistakes as the Chief Executive. GW worried more about committing an error than making a brilliant decision that would lead to a cacophony of "Huzzahs".

For example, Washington deliberated quite a while on the pros and cons of the proposed

Bill of Rights; he then actually changed his previous stance in opposition to adding amendments to the Constitution. GW's open support of the Bill of Rights broke the logjam in Congress in terms of their proposal for ratification.

For example, Washington deliberated quite a while on the pros and cons of the proposed

Bill of Rights; he then actually changed his previous stance in opposition to adding amendments to the Constitution. GW's open support of the Bill of Rights broke the logjam in Congress in terms of their proposal for ratification.