Source: Doug Stanton. In Harm's Way: The Sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis and

the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors (2003)

Also, here is a full television movie, "Mission of the Shark" (1991)

the Extraordinary Story of Its Survivors (2003)

Also, here is a full television movie, "Mission of the Shark" (1991)

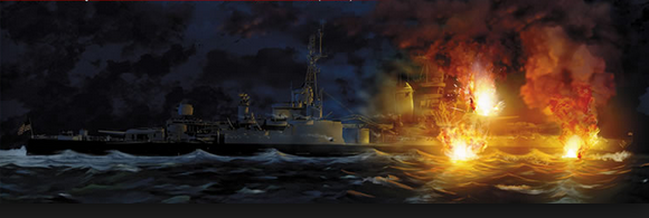

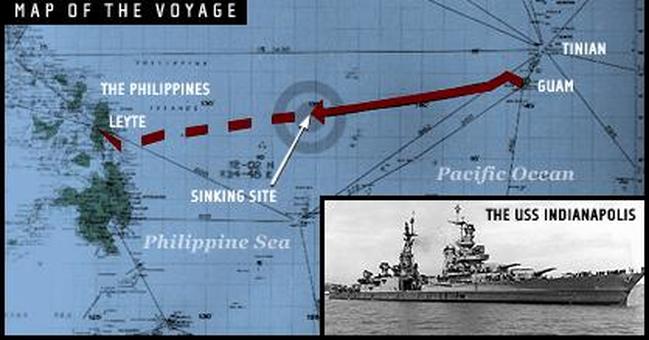

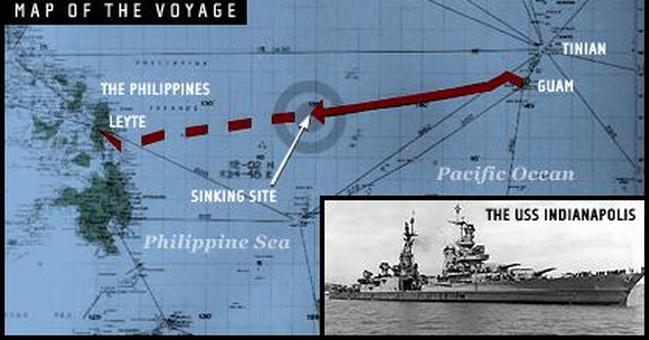

While the Indianapolis was sinking, an emergency SOS message HAD reached Naval Command at Leyte in The Philippines from a makeshift get-up from Radio Room #2. Commodore Jacob Jacobsen was awakened and apprised of the SOS, but no effort was made beyond that point. The SOS had reached another Leyte naval outpost, and the Officer of the Day dispatched two fast Navy tugboats to the site . . . but Commodore Norman Gillette recalled the tugs, since they sent without his authority. That SOS reached a THIRD Leyte outpost (a landing craft in the harbor); that craft signaled Leyte's Naval Operating Base, but did not receive any instructions . . . in the end, there were no immediate responses to the SOS.

The U.S. Navy's protocol was to treat messages that couldn't be confirmed as pranks, and it was a pro forma procedure by late-July, 1945; The Japanese often tried to confuse and expose the Navy in many locations. It was estimated that about 300 men died on the Indianapolis, and a little over 900 men entered the Pacific with Captain McVay. McVay had been sucked down with the ship, but a large air bubble brought him back to the surface. From the moment the first torpedo hit the ship to when the Indianapolis sank, only twelve minutes had elapsed . . . and the ship sank in one of the deepest ocean trenches on Earth.

The U.S. Navy's protocol was to treat messages that couldn't be confirmed as pranks, and it was a pro forma procedure by late-July, 1945; The Japanese often tried to confuse and expose the Navy in many locations. It was estimated that about 300 men died on the Indianapolis, and a little over 900 men entered the Pacific with Captain McVay. McVay had been sucked down with the ship, but a large air bubble brought him back to the surface. From the moment the first torpedo hit the ship to when the Indianapolis sank, only twelve minutes had elapsed . . . and the ship sank in one of the deepest ocean trenches on Earth.

Day One: Monday, 30 July, 1945

About half of the 900 in the water had a life vest or an inflatable life belt, but those belts were useless, since the fuel oil in the ocean had weakened the seams. For awhile, Captain McVay was by himself; he was in absolute hell, in that he assumed that he was the only survivor. Other than fuel oil on his face (and some in his eyes), he was in good physical shape.

(Pictured: a screen capture from the 1991 made-for-television movie "Mission of the Shark")

Once clear of the oil slicks, bobbing around in the Pacific was like being in a mildly acidic bath. Also, since most were getting constantly splashed in the face, the survivors were unwillingly ingesting seawater, their red blood cells were breaking down (leading to dehydration), and their lungs were slowly filling with water. One of the very few positives was that some survivors (including McVay) discovered that the fuel oil made an excellent sun screen.

By dusk on Monday, the sharks arrived, most likely attracted by the blood trail. There were hundreds of sharks, including tigers, makos, white-tips, and blues . . . the survivors thought that the bumps they were feeling were from their fellow crew mates.

(Below: a segment from "Mission of the Shark"; Captain McVay finds another survivor)

About half of the 900 in the water had a life vest or an inflatable life belt, but those belts were useless, since the fuel oil in the ocean had weakened the seams. For awhile, Captain McVay was by himself; he was in absolute hell, in that he assumed that he was the only survivor. Other than fuel oil on his face (and some in his eyes), he was in good physical shape.

(Pictured: a screen capture from the 1991 made-for-television movie "Mission of the Shark")

Once clear of the oil slicks, bobbing around in the Pacific was like being in a mildly acidic bath. Also, since most were getting constantly splashed in the face, the survivors were unwillingly ingesting seawater, their red blood cells were breaking down (leading to dehydration), and their lungs were slowly filling with water. One of the very few positives was that some survivors (including McVay) discovered that the fuel oil made an excellent sun screen.

By dusk on Monday, the sharks arrived, most likely attracted by the blood trail. There were hundreds of sharks, including tigers, makos, white-tips, and blues . . . the survivors thought that the bumps they were feeling were from their fellow crew mates.

(Below: a segment from "Mission of the Shark"; Captain McVay finds another survivor)

Day Two: Tuesday, 31 July, 1945

The sharks attacked around dawn, prowling in frenzied schools. There were two reasons why there was a high probability that many sharks had shadowed the Indianapolis for awhile. First, the ship's low-grade electrical current was an attraction, and secondly, there was a constant stream of refuse thrown overboard . . . the sharks were most likely a presence even before the Indianapolis was sunk. (pictured: a screen capture from "Mission of the Shark"; Captain McVay is in the center).

So far, the sharks had fed on the dead, but that was soon going to change. The sharks started to hone in on those that were partially clothed (white in blue water was also an attraction). To these sharks, the sailors most likely seemed to be similar to wounded fish. As the shark attacks increased, so did the frenzy and ferocity, since there was blood in the water.

Then, all of a sudden, the sharks stopped attacking, and returned to the lower levels of the Pacific; sharks prefer to attack (and feed) during dusk and dawn. Between attacks, more-and-more survivors were thinking about drinking seawater.

The sharks attacked around dawn, prowling in frenzied schools. There were two reasons why there was a high probability that many sharks had shadowed the Indianapolis for awhile. First, the ship's low-grade electrical current was an attraction, and secondly, there was a constant stream of refuse thrown overboard . . . the sharks were most likely a presence even before the Indianapolis was sunk. (pictured: a screen capture from "Mission of the Shark"; Captain McVay is in the center).

So far, the sharks had fed on the dead, but that was soon going to change. The sharks started to hone in on those that were partially clothed (white in blue water was also an attraction). To these sharks, the sailors most likely seemed to be similar to wounded fish. As the shark attacks increased, so did the frenzy and ferocity, since there was blood in the water.

Then, all of a sudden, the sharks stopped attacking, and returned to the lower levels of the Pacific; sharks prefer to attack (and feed) during dusk and dawn. Between attacks, more-and-more survivors were thinking about drinking seawater.

Although the water was 85 degrees, slow hypothermia still occurred, in that there was a ten-degree differential between the water and air temperature. Shivering quadrupled the rate of oxygen consumption, which caused the rate of hypothermia to occur faster. The body starts to slowly shut down under those circumstances (e.g. kidney failure), and in combination with ingesting seawater, many survivors would make fatal future judgments.

At Leyte, the Indianapolis was marked as "Arrived"; it was always assumed so if there was no information to the contrary. The current Navy policy was that the "arrival of combatant ships shall not be reported." So, there was no help for the survivors in the offing from Leyte, or anywhere else. (pictured: Capt. McVay and one of his crew on a life raft in "Mission of the Shark").

The survivors had reached the 40 hour mark since the Indianapolis sank, and there were probably only 600 or so still alive. "Will I Live" or "Will I Quit" were the questions among the survivors, and for those that gave up, suicide was common. By nightfall, many dehydrated survivors started to drink seawater, gorging themselves. In most cases, in only two hours, each survivor that did so died, since the body was overloaded with saline. Those that were most likely to resist drinking seawater . . . those that had families.

At Leyte, the Indianapolis was marked as "Arrived"; it was always assumed so if there was no information to the contrary. The current Navy policy was that the "arrival of combatant ships shall not be reported." So, there was no help for the survivors in the offing from Leyte, or anywhere else. (pictured: Capt. McVay and one of his crew on a life raft in "Mission of the Shark").

The survivors had reached the 40 hour mark since the Indianapolis sank, and there were probably only 600 or so still alive. "Will I Live" or "Will I Quit" were the questions among the survivors, and for those that gave up, suicide was common. By nightfall, many dehydrated survivors started to drink seawater, gorging themselves. In most cases, in only two hours, each survivor that did so died, since the body was overloaded with saline. Those that were most likely to resist drinking seawater . . . those that had families.

Day Three: Wednesday, 1 August, 1945

That morning, some survivors started killing other survivors . . . for them, there was no more hope left. In their hallucinations, they saw "Japs" everywhere, and they used their knives to attack and defend. In just one ten-minute span, fifty were killed - it was like a flash-fire. For the past three days, survivors had been dying on an average of one every ten minutes. McVay's survivors were relatively untouched by the madness that gripped the other groups (the survivors were scattered over miles of ocean). The overriding concerns of McVay's group was exhaustion . . . and sharks (pictured: screen capture from "Mission of the Shark").

That morning, some survivors started killing other survivors . . . for them, there was no more hope left. In their hallucinations, they saw "Japs" everywhere, and they used their knives to attack and defend. In just one ten-minute span, fifty were killed - it was like a flash-fire. For the past three days, survivors had been dying on an average of one every ten minutes. McVay's survivors were relatively untouched by the madness that gripped the other groups (the survivors were scattered over miles of ocean). The overriding concerns of McVay's group was exhaustion . . . and sharks (pictured: screen capture from "Mission of the Shark").

Days Four & Five: Thursday/Friday, 2 - 3 August, 1945

A small bomber plane was on patrol, looking for Japanese submarines, and its crew was struggling with its long-range radio antennae/sensor that extended behind the plane. It was weighted with a "sock", but that "sock" kept falling off, and they were in the midst of trying to solve the problem.

It was during this struggle for a "Plan B" that one of the crew members saw something that looked like an oil slick in the water as they flew by . . . to them, that meant there was probably a Japanese submarine in the area. The plane turned around, and prepared for a bombing run; they even had their depth charges ready to drop. On their first pass, they saw bodies in the water . . . it didn't matter whether they were friend or foe, the plane's crew had to think and act fast. (pictured: another screen capture from "Mission of the Shark").

The bombing run was aborted, and they readied for another pass. The pilot had to calculate their position by "dead-reckoning", since they had a loose antennae. At 11:25 am, the plane radioed-in their approximate position, making it clear that survivors were sighted . . . it was the first report of the Indianapolis disaster.

The survivors had drifted incredible distances, some over 100 miles in just four days. Using a piece of rubber hose, the plane's crew weighted down their loose antennae, and calculated an accurate fix on their position. A second, far-more-accurate position message was sent, and US forces at Peleliu (SW of their position) were mobilized for rescue. Radio traffic was heavy, and news spread to US Naval Command in Guam.

A small bomber plane was on patrol, looking for Japanese submarines, and its crew was struggling with its long-range radio antennae/sensor that extended behind the plane. It was weighted with a "sock", but that "sock" kept falling off, and they were in the midst of trying to solve the problem.

It was during this struggle for a "Plan B" that one of the crew members saw something that looked like an oil slick in the water as they flew by . . . to them, that meant there was probably a Japanese submarine in the area. The plane turned around, and prepared for a bombing run; they even had their depth charges ready to drop. On their first pass, they saw bodies in the water . . . it didn't matter whether they were friend or foe, the plane's crew had to think and act fast. (pictured: another screen capture from "Mission of the Shark").

The bombing run was aborted, and they readied for another pass. The pilot had to calculate their position by "dead-reckoning", since they had a loose antennae. At 11:25 am, the plane radioed-in their approximate position, making it clear that survivors were sighted . . . it was the first report of the Indianapolis disaster.

The survivors had drifted incredible distances, some over 100 miles in just four days. Using a piece of rubber hose, the plane's crew weighted down their loose antennae, and calculated an accurate fix on their position. A second, far-more-accurate position message was sent, and US forces at Peleliu (SW of their position) were mobilized for rescue. Radio traffic was heavy, and news spread to US Naval Command in Guam.

As a result of the first radio message, floating planes (PBY Catalinas) were sent to the area. One was to relieve the spotter plane, and the others were to land in the water for immediate assistance. But, since a Catalina was unable to get immediately airborne, a Ventura bomber was the first plane that was dispatched. Also, there were orders from Guam (NE of their position) to send two destroyers to rescue the survivors.

A separate amphibious plane spotted the survivors, and dropped all their gear in the ocean. They radioed for permission to put-down in order to assist the survivors . . . and permission to do so was actually denied. At least at this point Naval Command in The Philippines (CINCPAC) ordered all ships to break radio silence in order to report their position.

A separate amphibious plane spotted the survivors, and dropped all their gear in the ocean. They radioed for permission to put-down in order to assist the survivors . . . and permission to do so was actually denied. At least at this point Naval Command in The Philippines (CINCPAC) ordered all ships to break radio silence in order to report their position.

One of the Catalinas (pictured) decided to land in the ocean against orders; it was very risky; planes in that class were rarely successful in putting down in the ocean, as opposed to an enclosed bay or harbor. The crew landed despite almost tearing their plane apart, and they were taking on water due to torn rivets. Once in the water, the crew's goal was to collect as many survivors as possible before dark.

B-17's dropped much more equipment in the water, including larger rafts and wooden lifeboats. The Catalina in the water brought 56 survivors on board, many strapped down on the wings. The destroyer Cecil J. Doyle arrived at 11:45 pm, and started with rescuing the 50+ men on the Catalina. At 12:52 am (3 August) the high-speed transport ship Bassett arrived, and then the destroyers Ralph Talbot and Madison were on the scene, with the destroyer escort Dufilho soon to arrive as well. During the pre-dawn hours, the Bassett picked up 152 survivors, and then under orders returned to Leyte.

B-17's dropped much more equipment in the water, including larger rafts and wooden lifeboats. The Catalina in the water brought 56 survivors on board, many strapped down on the wings. The destroyer Cecil J. Doyle arrived at 11:45 pm, and started with rescuing the 50+ men on the Catalina. At 12:52 am (3 August) the high-speed transport ship Bassett arrived, and then the destroyers Ralph Talbot and Madison were on the scene, with the destroyer escort Dufilho soon to arrive as well. During the pre-dawn hours, the Bassett picked up 152 survivors, and then under orders returned to Leyte.

Day Five and After: 3 August, 1945 . . .

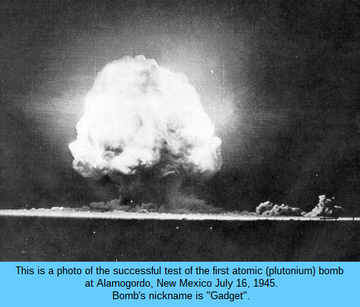

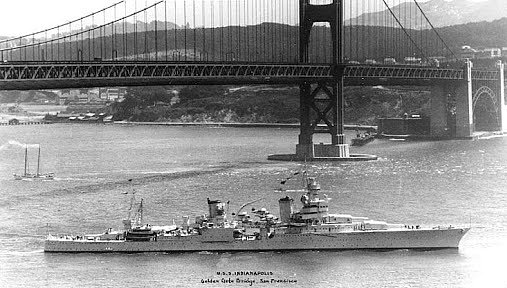

Top Navy brass (including Admiral Chester Nimitz) feared a "controversy" over the Indianapolis would mar the Navy's "Finest Hour" . . . they didn't want the Indianapolis disaster to take anything away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As soon as 3 August, the aftershocks of the Indianapolis disaster were rippling through Navy command. New rules were issued: no ships were allowed in the Pacific without escort, and every ship that was five-hours-or-more overdue were to report to the port from which they started . . . this was all far-too-late for the men of the Indianapolis.

By early morning on 3 August, Captain McVay had still not been found by rescuers. At 10 am, a ship (the high-speed transport Ringness) arrived, and by a stroke of good luck, their radar pinged on an ammunition can that McVay had tried to use as a beacon. Now that he was rescued, McVay’s thoughts drifted towards his imminent court-martial.

Top Navy brass (including Admiral Chester Nimitz) feared a "controversy" over the Indianapolis would mar the Navy's "Finest Hour" . . . they didn't want the Indianapolis disaster to take anything away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As soon as 3 August, the aftershocks of the Indianapolis disaster were rippling through Navy command. New rules were issued: no ships were allowed in the Pacific without escort, and every ship that was five-hours-or-more overdue were to report to the port from which they started . . . this was all far-too-late for the men of the Indianapolis.

By early morning on 3 August, Captain McVay had still not been found by rescuers. At 10 am, a ship (the high-speed transport Ringness) arrived, and by a stroke of good luck, their radar pinged on an ammunition can that McVay had tried to use as a beacon. Now that he was rescued, McVay’s thoughts drifted towards his imminent court-martial.

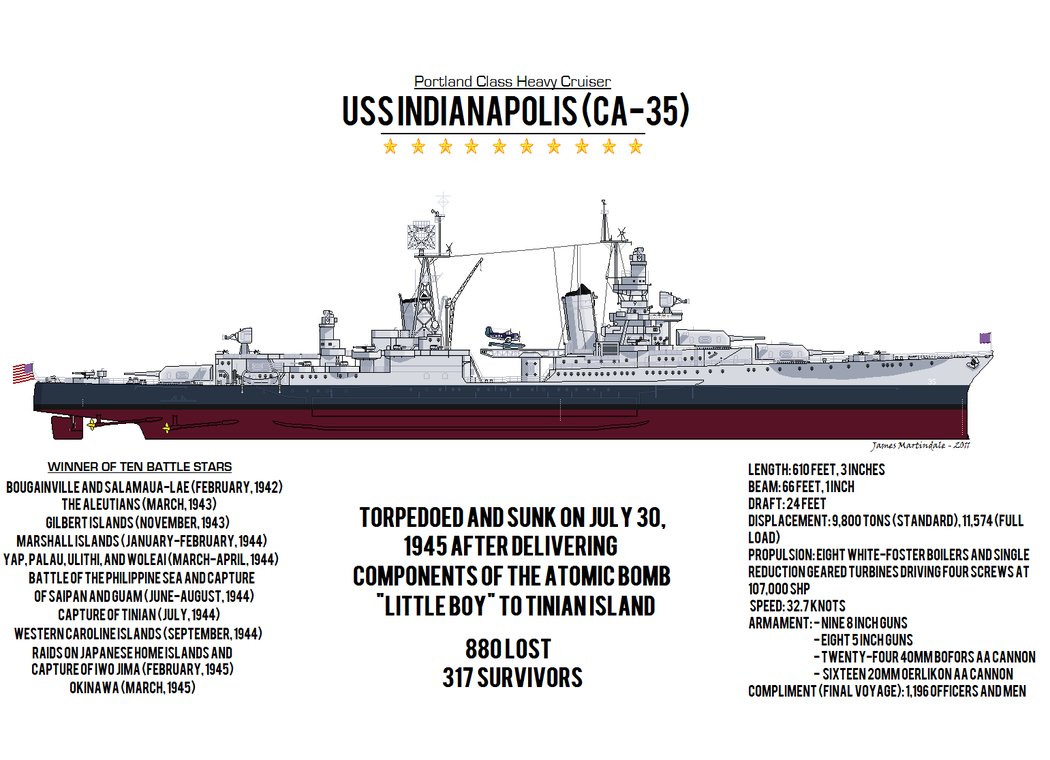

The last of the survivors pulled from the Pacific had been in the ocean for 112 hours, or more than four days. They had no food, water, or shelter from the sun, and they had drifted 124 miles from where the Indianapolis had sunk. Of the 1196 crew members, only 321 survived; 67 of the 81 officers and 808 enlisted men.

Four survivors would soon die in navy hospitals, reducing the number of survivors to 317; while there was no way to be certain, estimates were that as many as 200 survivors were killed by sharks. There was also the strong possibility that there were some survivors that were never rescued, despite the relentless and tireless efforts of plane-and-ship rescue crews during the following days and nights.

(Below: an actual photograph of some of the survivors of the Indianapolis on Guam)

Four survivors would soon die in navy hospitals, reducing the number of survivors to 317; while there was no way to be certain, estimates were that as many as 200 survivors were killed by sharks. There was also the strong possibility that there were some survivors that were never rescued, despite the relentless and tireless efforts of plane-and-ship rescue crews during the following days and nights.

(Below: an actual photograph of some of the survivors of the Indianapolis on Guam)

Here is the full television movie, "Mission of the Shark" (1991);

Stacy Keach portrays Captain Charles McVay III

Stacy Keach portrays Captain Charles McVay III