Source: Emily Arnold McCully. Ida M. Tarbell: The Woman Who

Challenged Big Business - And Won! (2014)

Challenged Big Business - And Won! (2014)

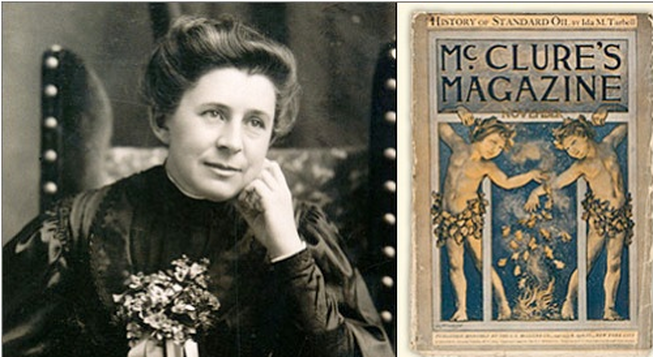

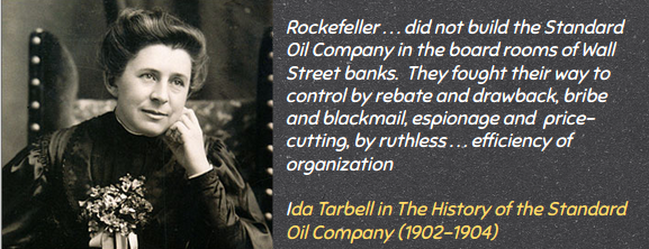

In November 1902, the first installment of "The History of the Standard Oil Company" (HSOC) appeared in McClure's Magazine, written by Ida Tarbell. Even though the HSOC series had started, Tarbell's research was very difficult and complicated in that Rockefeller insisted on anonymity and was mostly invisible in the relevant Standard Oil documents; Rockefeller ruled his empire with winks, nods, hints, and handshakes . . . all designed to derail any investigation.

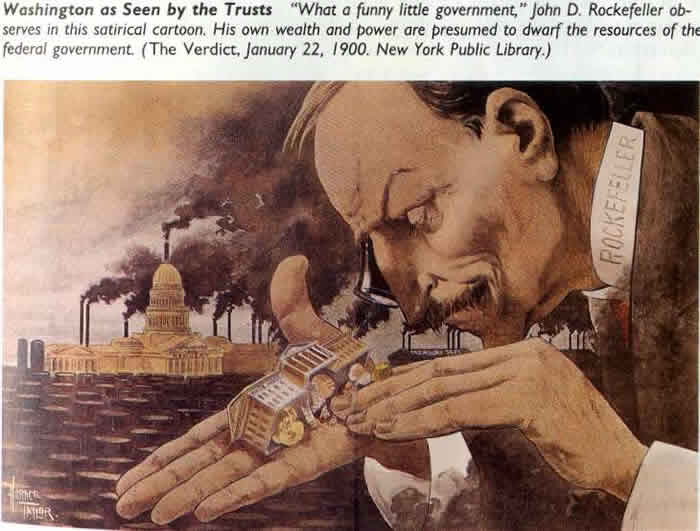

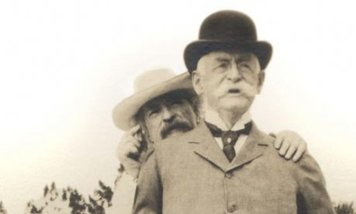

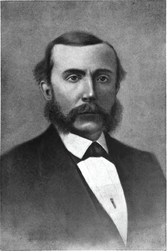

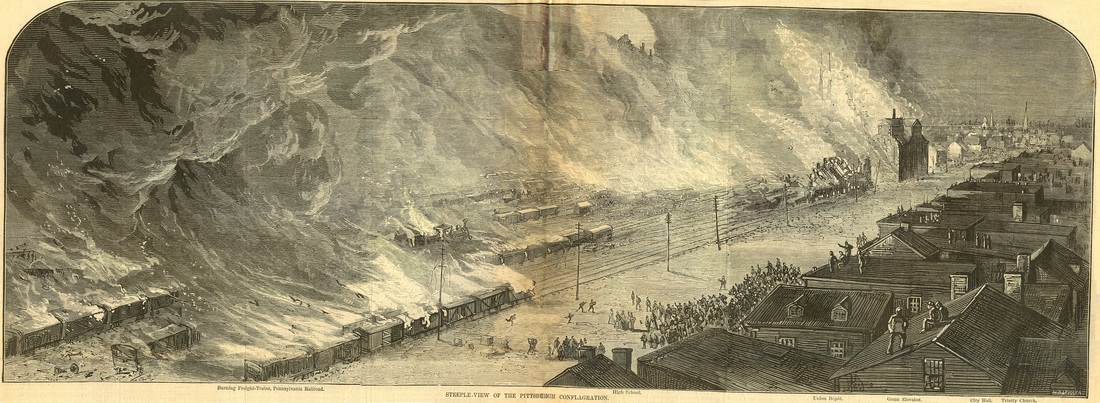

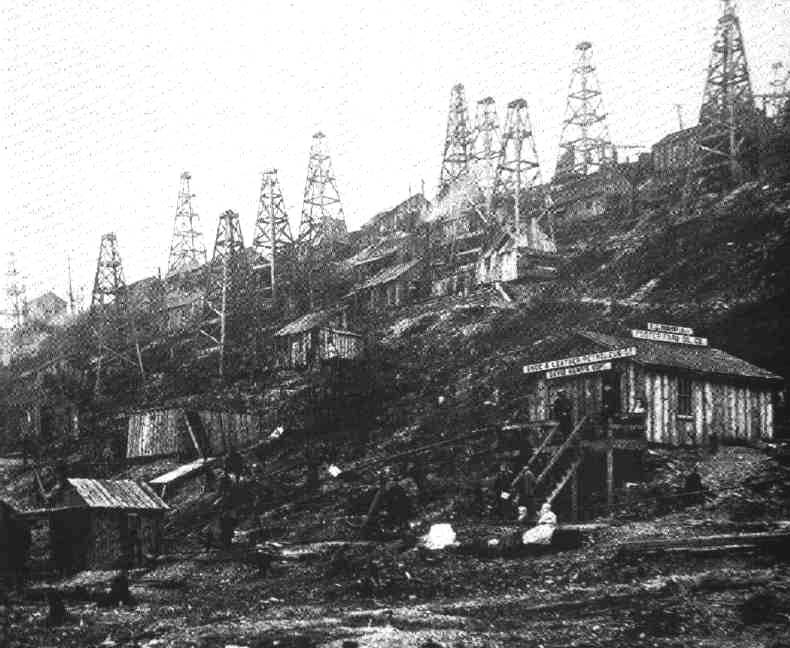

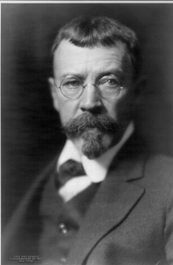

Tarbell portrayed the independent oil producers as "Innocents" who risked everything in their ventures, and then a malevolent "Big Hand" (Rockefeller) came down and swatted them. Ida also wrote a separate article about the labor violence in the coal industry (Tarbell had little sympathy for labor union leaders), while Lincoln Steffens (pictured) wrote an article on the corruption in city governments for McClure's. All three articles were designed to show that the "American Contempt for the Law" negatively affected the public good.

Tarbell portrayed the independent oil producers as "Innocents" who risked everything in their ventures, and then a malevolent "Big Hand" (Rockefeller) came down and swatted them. Ida also wrote a separate article about the labor violence in the coal industry (Tarbell had little sympathy for labor union leaders), while Lincoln Steffens (pictured) wrote an article on the corruption in city governments for McClure's. All three articles were designed to show that the "American Contempt for the Law" negatively affected the public good.

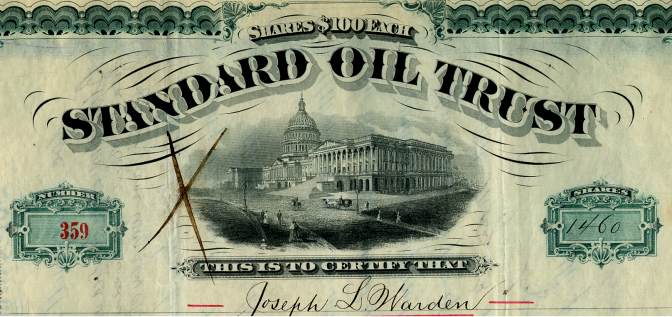

In effect, these three articles were the real birth of "Muckraking", which used the following formula: first, quality investigation exposes a major problem, then citizens read the article, then the citizens mobilize, and demand change. One of Tarbell's leading researchers discovered proof that Standard Oil had started manipulating prices in 1876; he found a memo from Henry Flagler (Rockefeller's major partner) which stated that an increase of a quarter-cent per barrel would net Standard Oil millions of dollars. Tarbell's goal in exposing the document was to show that Standard Oil's goal was to always artificially increase prices for the consumer, for the benefit of Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

Tarbell contended that the independents welcomed competition (that basically wasn't true; Tarbell didn't have a great grasp on the mechanics and motivations within markets), and Rockefeller wanted to crush competition (that was absolutely true). Tarbell described a takeover by Standard Oil of an independent pipeline that used espionage, sabotage of a Buffalo refinery, and rigging an Ohio U.S. Senate election.

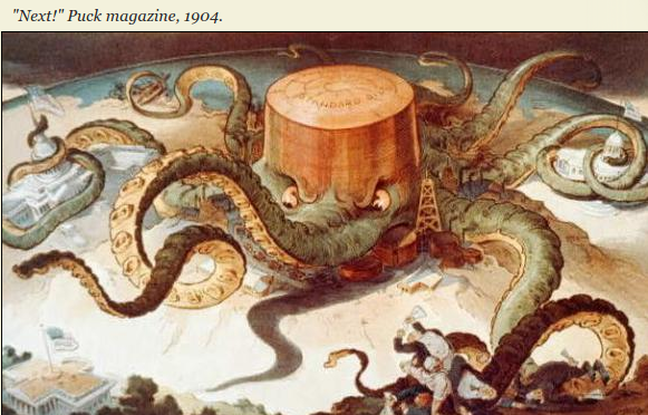

Even though Tarbell extolled the virtues of the independents, in private she became disillusioned about her heroes; her wrath with them was as great as with Rockefeller. Ida thought that the independents always seemed to make the wrong decisions and flunk-out at every critical juncture, but she kept her official written focus on the Standard Oil Trust (SOT) and Rockefeller . . . she kept going after "The Octopus".

Tarbell contended that the independents welcomed competition (that basically wasn't true; Tarbell didn't have a great grasp on the mechanics and motivations within markets), and Rockefeller wanted to crush competition (that was absolutely true). Tarbell described a takeover by Standard Oil of an independent pipeline that used espionage, sabotage of a Buffalo refinery, and rigging an Ohio U.S. Senate election.

Even though Tarbell extolled the virtues of the independents, in private she became disillusioned about her heroes; her wrath with them was as great as with Rockefeller. Ida thought that the independents always seemed to make the wrong decisions and flunk-out at every critical juncture, but she kept her official written focus on the Standard Oil Trust (SOT) and Rockefeller . . . she kept going after "The Octopus".

Rockefeller's extreme elusiveness was in part due to the fact that he had lost all of his hair; that elusiveness cost him in that it worsened his reputation with the American public. Henry Demarest Lloyd, the first journalist to expose Rockefeller's decisions and practices with Standard Oil, finally agreed to meet with Tarbell. Lloyd documented that the railroad rebates were still occurring and benefiting Standard Oil, and the records of the rebates were continually destroyed. Ida borrowed documents from Lloyd's files, and used what she discovered in her HSOC series.

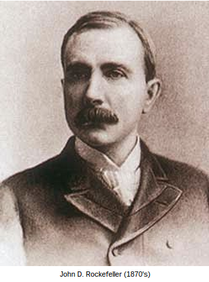

By 1904, Ida and her researchers still hadn't found a recent photograph of Rockefeller, and to Tarbell, the HSOC wasn't complete without one. Ida and her main assistant decided to attend Rockefeller's Baptist church incognito, using other parishioners as "cover". Also, a sketch artist would be with them in the church as well, and his sketch from the "secret mission" is pictured above.

By 1904, Ida and her researchers still hadn't found a recent photograph of Rockefeller, and to Tarbell, the HSOC wasn't complete without one. Ida and her main assistant decided to attend Rockefeller's Baptist church incognito, using other parishioners as "cover". Also, a sketch artist would be with them in the church as well, and his sketch from the "secret mission" is pictured above.

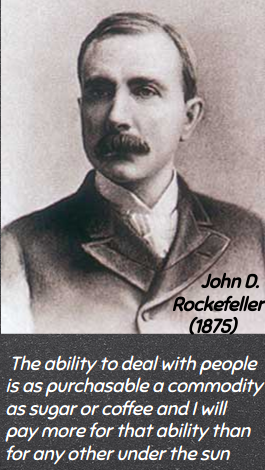

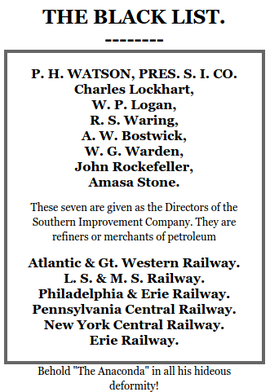

Men like Rockefeller were accustomed to living and operating with no regard for public opinion. But privately, Rockefeller referred to Ida as "Miss Tarbarrel" during the run of the HSOC in McClure's Magazine (1902-1904). Rockefeller and his family fell ill with one ailment or another during the run of the HSOC; "Junior" suffered the most, suffering from a mental breakdown. After "The History of the Standard Oil Company" finished its run, Tarbell followed with a "Character Sketch" of Rockefeller, focusing on a key point in time: Rockefeller's decision to pursue the South Improvement Company (SIC) - to Tarbell, that was the point-in-time where Rockefeller chose evil instead of good (Ida used searing language in her "sketch").

Tarbell stated that a man of Rockefeller's power and influence should not be able to "Live in the Dark"; he was the victim of "Money Passion", which blinded him to the good in life (according to Mark Hanna, Rockefeller was "Money Mad . . . sane in every other way . . . but "Money Mad"). Tarbell's only praises for Rockefeller were that he was a good husband and father, and lived far more economically than other tycoons (tycoon is based on a Japanese word that meant "Great Lord").

In the second installment of her "Character Sketch" on Rockefeller, Ida found a formal photograph, and based the installment on her observations of Rockefeller's face, asking readers to do the same. To Ida, the photograph of Rockefeller (pictured on the cover of McClure's, above) combined with the "Church Sketch" showed concentration, cruelty, craftiness . . . a repulsive "Living Mummy", who was far too stealthy and secretive for the public good (Ida even proved that Rockefeller's father, a known scoundrel, had been indicted for horse theft and rape). After her "Character Sketch" on Rockefeller, Ida Tarbell became the most famous woman in America (in part that was also due to the decline in popularity of Jane Addams in the early-1900's).

Tarbell stated that a man of Rockefeller's power and influence should not be able to "Live in the Dark"; he was the victim of "Money Passion", which blinded him to the good in life (according to Mark Hanna, Rockefeller was "Money Mad . . . sane in every other way . . . but "Money Mad"). Tarbell's only praises for Rockefeller were that he was a good husband and father, and lived far more economically than other tycoons (tycoon is based on a Japanese word that meant "Great Lord").

In the second installment of her "Character Sketch" on Rockefeller, Ida found a formal photograph, and based the installment on her observations of Rockefeller's face, asking readers to do the same. To Ida, the photograph of Rockefeller (pictured on the cover of McClure's, above) combined with the "Church Sketch" showed concentration, cruelty, craftiness . . . a repulsive "Living Mummy", who was far too stealthy and secretive for the public good (Ida even proved that Rockefeller's father, a known scoundrel, had been indicted for horse theft and rape). After her "Character Sketch" on Rockefeller, Ida Tarbell became the most famous woman in America (in part that was also due to the decline in popularity of Jane Addams in the early-1900's).

All the while, Rockefeller never personally disputed Tarbell's findings or assertions in public. He probably believed such public responses were "beneath him", but he also didn't want to open any door to other investigations. Rockefeller could have ruined McClure's Magazine (and

S.S. McClure's publishing empire) by influencing and intimidating advertisers, but he was confident that his secret business methods would remain secret . . . he felt safe from further exposure.

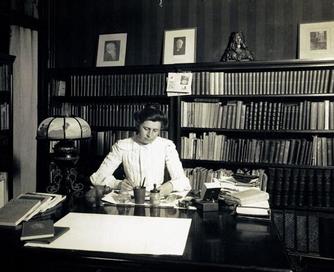

Ida Tarbell (pictured at her desk at McClure's in 1905) condemned the practices of the Standard Oil Trust, but not the practice of Capitalism in general - Tarbell didn't have any problem with Combinations that used ethical means to earn profits. To Tarbell, Rockefeller's potential for greatness was ruined because he didn't played fair . . . in 1906, the Attorney General (Charles J. Bonaparte) agreed, in that he prosecuted Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Trust for unfair business practices under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890).

S.S. McClure's publishing empire) by influencing and intimidating advertisers, but he was confident that his secret business methods would remain secret . . . he felt safe from further exposure.

Ida Tarbell (pictured at her desk at McClure's in 1905) condemned the practices of the Standard Oil Trust, but not the practice of Capitalism in general - Tarbell didn't have any problem with Combinations that used ethical means to earn profits. To Tarbell, Rockefeller's potential for greatness was ruined because he didn't played fair . . . in 1906, the Attorney General (Charles J. Bonaparte) agreed, in that he prosecuted Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Trust for unfair business practices under the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (1890).