Source: Steve Sheinkin. The Notorious Benedict Arnold - A True

Story of Adventure, Heroism, and Treachery (2010)

Story of Adventure, Heroism, and Treachery (2010)

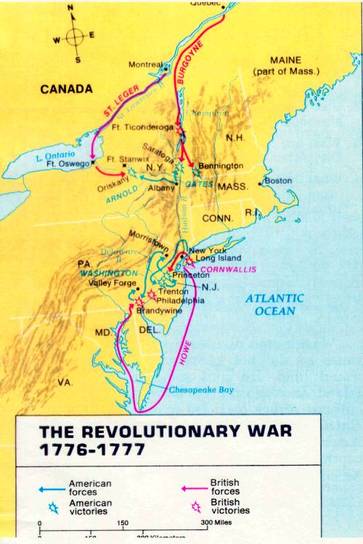

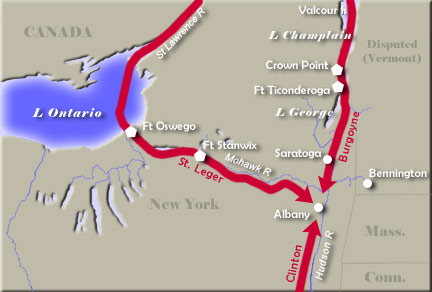

On 4 May 1778, General Benedict Arnold finally returned to his home at New Haven, Connecticut, and was greeted as the "Hero of Saratoga". On 18 May 1778, British officer John Andre's all-day extravaganza (it was more like an elegant carnival) for General Howe occurred in Philadelphia. Unbeknownst to either Arnold or Andre, they would soon work together to try and win the war for Great Britain.

On 21 May 1778, Arnold arrived at Valley Forge (PA) and met with General George Washington. Washington knew that Arnold's fighting days were over, so he wanted Arnold to be the military governor of Philadelphia, once the British left (which his spies told him would be soon). The job would call for skills that Arnold didn't have in abundance: patience, tact, and political skill. For reasons that nobody has yet figured out, Washington offered the post to Arnold.

Philadelphia was of no strategic value for Britain, so Washington's spies were correct: the British forces in Philadelphia went to New York City. Major John Andre said goodbye to a young lady whose acquaintance he had made in Philadelphia, Margaret Shippen, the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia Loyalist (and soon to be the 2nd Mrs. Benedict Arnold).

Arnold entered Philadelphia in the center of a large parade in full dress uniform, smiling and waving to the crowd. Washington's instructions to Arnold were to adopt certain measures that were effective-yet-least-offensive in order to restore order. But Arnold started to offend the citizens of Philadelphia almost immediately; he was determined to live like a supreme leader, and it was an irritating (and rude) display of luxury to a city that was in shambles.

On 21 May 1778, Arnold arrived at Valley Forge (PA) and met with General George Washington. Washington knew that Arnold's fighting days were over, so he wanted Arnold to be the military governor of Philadelphia, once the British left (which his spies told him would be soon). The job would call for skills that Arnold didn't have in abundance: patience, tact, and political skill. For reasons that nobody has yet figured out, Washington offered the post to Arnold.

Philadelphia was of no strategic value for Britain, so Washington's spies were correct: the British forces in Philadelphia went to New York City. Major John Andre said goodbye to a young lady whose acquaintance he had made in Philadelphia, Margaret Shippen, the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia Loyalist (and soon to be the 2nd Mrs. Benedict Arnold).

Arnold entered Philadelphia in the center of a large parade in full dress uniform, smiling and waving to the crowd. Washington's instructions to Arnold were to adopt certain measures that were effective-yet-least-offensive in order to restore order. But Arnold started to offend the citizens of Philadelphia almost immediately; he was determined to live like a supreme leader, and it was an irritating (and rude) display of luxury to a city that was in shambles.

The citizens of Philadelphia wondered where Arnold obtained large amounts of money. Arnold had made a huge profit from confiscated stores on an American cargo ship, which wasn't exactly illegal, but it certainly wasn't ethical. Arnold kept quiet about the details that lead to his wealth; he felt more-than-entitled to that wealth since he had served with great distinction, but hadn't received the respect/glory he felt he deserved, and that he had also lost his robust health.

Joseph Reed was a successful Philadelphia lawyer, and a former aide to Washington, and was Vice-President of the Pennsylvania Executive Council that actually administered the city of Philadelphia. Reed hated seeing military leaders get so popular, and was also jealous of Arnold. Reed wanted to cut the military leaders down-to-size while there was still time to do so; to Reed, Arnold was no longer doing the work of the Revolution. At a gala dance, Arnold asked to be introduced to Peggy Shippen; after a small chat, he was smitten. Peggy was also intrigued with Arnold, and soon Arnold's fancy coach was often spotted in front of the Shippen mansion.

Finally, Arnold was able to walk without crutches. The best cobbler in Philadelphia made a special high heel for his (shorter) left leg. Arnold strolled the streets of Philadelphia with a limp (and a cane), ignoring the fierce storm between Loyalists, Patriots, and neutrals that raged around him . . . by that time, everything in Philadelphia was political. Arnold was even accused of inviting Tory (Loyalist) ladies to galas, which was true, but Arnold just wanted to be entertained and he enjoyed female company (as did Benjamin Franklin and George Washington).

Joseph Reed was a successful Philadelphia lawyer, and a former aide to Washington, and was Vice-President of the Pennsylvania Executive Council that actually administered the city of Philadelphia. Reed hated seeing military leaders get so popular, and was also jealous of Arnold. Reed wanted to cut the military leaders down-to-size while there was still time to do so; to Reed, Arnold was no longer doing the work of the Revolution. At a gala dance, Arnold asked to be introduced to Peggy Shippen; after a small chat, he was smitten. Peggy was also intrigued with Arnold, and soon Arnold's fancy coach was often spotted in front of the Shippen mansion.

Finally, Arnold was able to walk without crutches. The best cobbler in Philadelphia made a special high heel for his (shorter) left leg. Arnold strolled the streets of Philadelphia with a limp (and a cane), ignoring the fierce storm between Loyalists, Patriots, and neutrals that raged around him . . . by that time, everything in Philadelphia was political. Arnold was even accused of inviting Tory (Loyalist) ladies to galas, which was true, but Arnold just wanted to be entertained and he enjoyed female company (as did Benjamin Franklin and George Washington).

While Arnold and Peggy were doing well together, Arnold and the Pennsylvania legislature were not; the legislature was convinced that American military officers were starting to act like British aristocrats. Arnold purchased Mount Pleasant, which was a mansion on 90 acres overlooking the Schuylkill River, and easily one of the grandest estates in Philadelphia.

Reed became the preeminent figure in the Pennsylvania Executive Council, which not only made him more powerful, but also increased his obsession with destroying Arnold. Reed started to officially investigate the source of Arnold's wealth, and he used the city's newspapers to mount a smear campaign against Arnold. Arnold should have ignored the investigation and attacks, but of course he took it all personally, and had to respond. Then, in a newspaper article came specific mention of the rumors surrounding Arnold and Montreal (false accusations in which Arnold was accused of stealing supplies for his retreating soldiers after the failure at Quebec in 1775). Arnold responded with contempt for all Pennsylvania officials; by then, even Arnold understood it was probably time to leave Philadelphia.

Reed became the preeminent figure in the Pennsylvania Executive Council, which not only made him more powerful, but also increased his obsession with destroying Arnold. Reed started to officially investigate the source of Arnold's wealth, and he used the city's newspapers to mount a smear campaign against Arnold. Arnold should have ignored the investigation and attacks, but of course he took it all personally, and had to respond. Then, in a newspaper article came specific mention of the rumors surrounding Arnold and Montreal (false accusations in which Arnold was accused of stealing supplies for his retreating soldiers after the failure at Quebec in 1775). Arnold responded with contempt for all Pennsylvania officials; by then, even Arnold understood it was probably time to leave Philadelphia.

In February 1779, Arnold went to Washington to discuss options; Reed panicked, believing that he was losing his chance to destroy Arnold. Arnold was almost to Washington's HQ when he was shown a newspaper from a stranger. Contained in an article were the formal charges against Arnold from the Pennsylvania Executive Council. The Council accused Arnold of everything they could dream up, including illegal purchases, illegal use of public wagons for personal gain, and disrespectful treatment of militiamen and government leaders.

Arnold showed Washington the charges contained in the newspaper; Washington advised Arnold to go back to Philadelphia and deal with the problem. Washington was thinking politically, which was very common for the general, but Arnold thought that even Washington doubted his honor . . . it was a turning point for Arnold in terms of his relationship with Washington.

Andre quickly became General Henry Clinton's closest aide. Clinton was a very difficult general to serve, since he was perpetually moody, distant, a loner, and always appeared to be annoyed. Other officers avoided Clinton, but Andre took a liking to the general, and was able to break through Clinton's veneer. Andre was promoted to major, and in effect became Clinton's Chief-of-Staff . . . Andre was becoming an important man in New York City, and he loved it for every minute.

In April 1779, Clinton named Andre his Chief of Intelligence, which meant he was in charge of Clinton's spy network. Andre was 28, which aggravated the older, more senior officers; to them, Andre was a "cringing, insidious sycophant". Andre was fully aware that he was on a figurative ledge, and that many were rooting for him to fall . . . Andre was supremely motivated to show them he was the right man for the post - he wanted to pull off an amazing coup as the Intelligence Chief.

Arnold showed Washington the charges contained in the newspaper; Washington advised Arnold to go back to Philadelphia and deal with the problem. Washington was thinking politically, which was very common for the general, but Arnold thought that even Washington doubted his honor . . . it was a turning point for Arnold in terms of his relationship with Washington.

Andre quickly became General Henry Clinton's closest aide. Clinton was a very difficult general to serve, since he was perpetually moody, distant, a loner, and always appeared to be annoyed. Other officers avoided Clinton, but Andre took a liking to the general, and was able to break through Clinton's veneer. Andre was promoted to major, and in effect became Clinton's Chief-of-Staff . . . Andre was becoming an important man in New York City, and he loved it for every minute.

In April 1779, Clinton named Andre his Chief of Intelligence, which meant he was in charge of Clinton's spy network. Andre was 28, which aggravated the older, more senior officers; to them, Andre was a "cringing, insidious sycophant". Andre was fully aware that he was on a figurative ledge, and that many were rooting for him to fall . . . Andre was supremely motivated to show them he was the right man for the post - he wanted to pull off an amazing coup as the Intelligence Chief.

On 8 April 1779, Arnold and Peggy were married in the Shippen mansion. The charges against Arnold were national news, and Arnold was quickly running out of money; he was bleeding cash trying to keep his extravagant standard-of-living. Soon, Arnold started to borrow money to keep up appearances, and Arnold and Peggy largely kept to themselves . . . this was when the treasonous plot was most likely hatched.

Congress had to decide the Arnold v. Pennsylvania debacle, but they couldn't find any evidence of illegal trading by Arnold. Congress then in effect transferred the entire mess to Washington, telling him to try Arnold in a military court. Arnold asked for a quick trial, but Reed objected, saying he needed more time to gather evidence. Reed went so far as to write Washington that if he didn't get the extra time, then Pennsylvania's support of the war effort just might decrease.

Washington was in an impossible position, and decided to postpone Arnold's trial. Arnold believed that the delay meant that Washington also saw him as a criminal, which proved to be another step towards treason. Arnold stated that the delay was worse-than-death; Arnold was most likely wrestling with his inner-demons by that time, and was heading towards some dreadful decisions. It was almost like Arnold was asking Washington to save him before it was too late.

Congress had to decide the Arnold v. Pennsylvania debacle, but they couldn't find any evidence of illegal trading by Arnold. Congress then in effect transferred the entire mess to Washington, telling him to try Arnold in a military court. Arnold asked for a quick trial, but Reed objected, saying he needed more time to gather evidence. Reed went so far as to write Washington that if he didn't get the extra time, then Pennsylvania's support of the war effort just might decrease.

Washington was in an impossible position, and decided to postpone Arnold's trial. Arnold believed that the delay meant that Washington also saw him as a criminal, which proved to be another step towards treason. Arnold stated that the delay was worse-than-death; Arnold was most likely wrestling with his inner-demons by that time, and was heading towards some dreadful decisions. It was almost like Arnold was asking Washington to save him before it was too late.

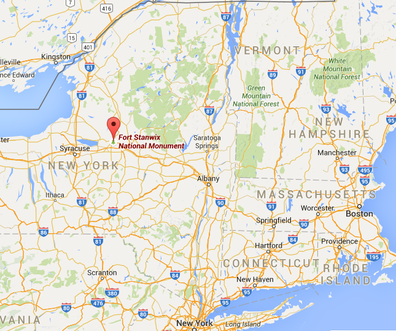

Major Andre had a hard time knowing which people visiting his office were actually spies, and whether they were credible or crackpots. On 10 May 1779, Joseph Stansbury visited Andre and told him that General Benedict Arnold was offering his services to General Henry Clinton, either by joining the British army or by being part of a covert operation. Andre was in absolute shock . . . it never even remotely registered to any British officer that Arnold was anything but a true Patriot.

A few days later, Stansbury told Arnold that his offer had been accepted, and that Andre urged Arnold to propose a specific plan of action. Peggy Arnold was the go-between, and invisible ink from onion juice was used; their cypher was Blackstone's Commentaries, a massive legal text familiar to the well-educated. The code/cypher was impossible to break, but it was also very slow and tedious to decode.

Arnold inquired about financial details, while Andre wanted information in order to find a weak spot in the American defenses. Andre made it very clear to Arnold that he needed to return to an important command in the American Army. Arnold saw Washington at his headquarters on 1 June 1779, just before his long-delayed court-martial was to begin. Arnold started ranting about Congress and Reed, and Washington didn't want to be seen talking to Arnold in any meaningful public way before the court-martial due to perceptions of fairness. As a result, Washington gave Arnold a fairly stern public rebuke; as a result, Arnold no longer had second thoughts of treason . . . his inner-demons were no more.

A few days later, Stansbury told Arnold that his offer had been accepted, and that Andre urged Arnold to propose a specific plan of action. Peggy Arnold was the go-between, and invisible ink from onion juice was used; their cypher was Blackstone's Commentaries, a massive legal text familiar to the well-educated. The code/cypher was impossible to break, but it was also very slow and tedious to decode.

Arnold inquired about financial details, while Andre wanted information in order to find a weak spot in the American defenses. Andre made it very clear to Arnold that he needed to return to an important command in the American Army. Arnold saw Washington at his headquarters on 1 June 1779, just before his long-delayed court-martial was to begin. Arnold started ranting about Congress and Reed, and Washington didn't want to be seen talking to Arnold in any meaningful public way before the court-martial due to perceptions of fairness. As a result, Washington gave Arnold a fairly stern public rebuke; as a result, Arnold no longer had second thoughts of treason . . . his inner-demons were no more.