In Cleveland, Ohio, 1855, John Davidson Rockefeller earned $25/month ($626 today) as a grocery store bookkeeper. Rockefeller was the son of a con man, and he had startlingly opposite traits from his father, such as personal discipline, determination, religious conviction, and sky-high ambition. To Rockefeller, acquiring wealth meant that he had to gain strict and total control of himself, and the market (which would eventually mean a monopoly . . . in something).

The only characteristic passed on from his father was a willingness to take gigantic risks. Rockefeller felt superior in his virtue, and came to despise men that thought they were better than him. Once he got the upper-hand, sudden vengeance would belong to Rockefeller.

Rockefeller arrived in "Oil Country" in 1860. "Oil Country" (in terms of drilling for oil) was Northwest Pennsylvania, and the center of region was Titusville, a city of 10,000+. Rockefeller almost immediately saw that refining oil to make money involved little expense and high potential profits compared to drilling for oil.

The only characteristic passed on from his father was a willingness to take gigantic risks. Rockefeller felt superior in his virtue, and came to despise men that thought they were better than him. Once he got the upper-hand, sudden vengeance would belong to Rockefeller.

Rockefeller arrived in "Oil Country" in 1860. "Oil Country" (in terms of drilling for oil) was Northwest Pennsylvania, and the center of region was Titusville, a city of 10,000+. Rockefeller almost immediately saw that refining oil to make money involved little expense and high potential profits compared to drilling for oil.

Soon, there were fifty refineries crowded around Cleveland, Ohio, including a refinery owned by John D. Rockefeller, and his partner Henry Flagler. Consistent with his belief of strict control over a market (to increase efficiency, production, and, of course, profits), Rockefeller started to absorb his rival refiners (in this "horizontal monopoly", Rockefeller gave his rivals a choice: sell for some level of profit, or be forced out of business).

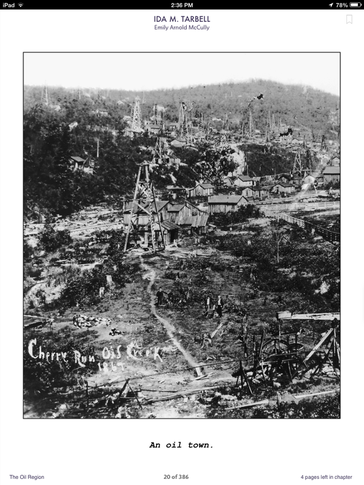

The other key to controlling the refining market was transportation of the refined product (initially kerosene, a.k.a. coal oil), which meant dealing with the railroads. A transportation monopoly existed in the Oil Region, in that the Erie, Central, and Pennsylvania Railroads were in collusion with each other. In an effort to extract even more control over the oil industry, these three railroad behemoths created the South Improvement Company. (Pictured: oil derricks in close proximity in NW PA in the 1860s).

Through this new company, this railroad Combination increased freight rates by 250%. However, the Combination let it be known that if an oil refiner joined the SIC, then that refiner would get a "rebate" (discount) on freight charges (they were pledged to secrecy, since it was against the law) . . . among the few refiners that joined the SIC was John D. Rockefeller (he also helped create the SIC). The 250% rate increase hit the refiners living in Titusville, Pennsylvania between the eyes, and these independent refiners made sure that the SIC was exposed to the daylight of public awareness.

The other key to controlling the refining market was transportation of the refined product (initially kerosene, a.k.a. coal oil), which meant dealing with the railroads. A transportation monopoly existed in the Oil Region, in that the Erie, Central, and Pennsylvania Railroads were in collusion with each other. In an effort to extract even more control over the oil industry, these three railroad behemoths created the South Improvement Company. (Pictured: oil derricks in close proximity in NW PA in the 1860s).

Through this new company, this railroad Combination increased freight rates by 250%. However, the Combination let it be known that if an oil refiner joined the SIC, then that refiner would get a "rebate" (discount) on freight charges (they were pledged to secrecy, since it was against the law) . . . among the few refiners that joined the SIC was John D. Rockefeller (he also helped create the SIC). The 250% rate increase hit the refiners living in Titusville, Pennsylvania between the eyes, and these independent refiners made sure that the SIC was exposed to the daylight of public awareness.

The Oil City Derrick newspaper printed the names of the refiners that had joined the South Improvement Company, and Rockefeller's name was on the list. Franklin Tarbell (Ida Tarbell's father), a partner in one of the independent refining companies, became a changed man: he stopped whistling, no longer played his harmonica, and stopped making jokes. Franklin even joined vigilante groups that wrecked SIC railroad tank cars. More effective (for a short while) was the embargo against Rockefeller's Standard Oil, in which Franklin Tarbell enthusiastically participated.

Franklin personally turned down Rockefeller's offer to buy a full year's output from his refinery (which was a way to start the process of "absorbing" a rival refinery). Franklin simply dismissed Rockefeller's strategy/tactics as morally wrong; both Franklin Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller believed they were on the side of "right". Rockefeller believed that Standard Oil had rescued the oil industry, and had emerged as the "fittest" company ("Social-Darwinism" was in the nation's bloodstream by that time in history); the term that Rockefeller used to describe his intervention (and collusion with the railroads) was "Cooperation". Franklin Tarbell believed that the railroads were to serve the public (as did most Americans), not a select group, such as the Southern Improvement Company.

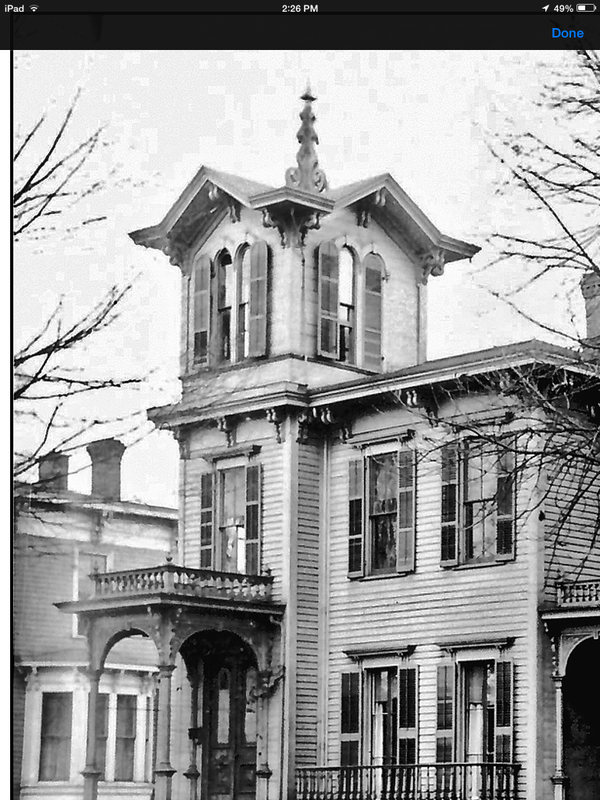

(Pictured: an "Oil Town")

Franklin personally turned down Rockefeller's offer to buy a full year's output from his refinery (which was a way to start the process of "absorbing" a rival refinery). Franklin simply dismissed Rockefeller's strategy/tactics as morally wrong; both Franklin Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller believed they were on the side of "right". Rockefeller believed that Standard Oil had rescued the oil industry, and had emerged as the "fittest" company ("Social-Darwinism" was in the nation's bloodstream by that time in history); the term that Rockefeller used to describe his intervention (and collusion with the railroads) was "Cooperation". Franklin Tarbell believed that the railroads were to serve the public (as did most Americans), not a select group, such as the Southern Improvement Company.

(Pictured: an "Oil Town")

To Ida Tarbell (Franklin's daughter), the dispute over the SIC hit home very hard, seeing how it had affected her father. In her mid-teens, Ida developed a hatred of the "Privileged Class", the unchecked wealthy and powerful that had negatively altered her life and that of her family. It became obvious to the independent refiners (and a young Ida Tarbell) that if the SIC controlled the transportation of oil, they were soon to be forced out of business.

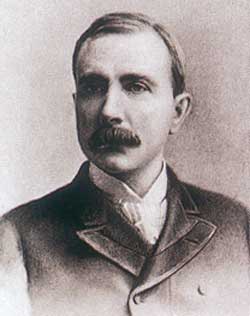

On 25 March, 1872, the Railroad Combination (Erie, Central, PA) conceded defeat, and canceled the SIC contract. In their euphoria from (a perceived) victory, the independent refiners did their best to exclude and ostracize Rockefeller, since he was the alleged (and actual) leader of the SIC. Little did they know at the time that the fall of the SIC wasn't going to slow down Rockefeller in the least. He already controlled 22 of the 26 refineries in the Oil Region, which meant that Rockefeller (pictured above in 1875) was in a position to keep making secret deals with the railroads. To Ida Tarbell, her father represented the "Noble Underdog" who was overwhelmed by the "Evil Empire" . . . and Rockefeller was her Darth Vader.

(When times were good for Franklin Tarbell, he moved his family to a better location. He purchased an abandoned hotel in a nearby oil ghost town for $600 ($10k today) and had it transported piece-by-piece to a plot of land he had just purchased . . . below, you see the new Tarbell home, which was completely reassembled in the early-1870s in Titusville, Pennsylvania)

On 25 March, 1872, the Railroad Combination (Erie, Central, PA) conceded defeat, and canceled the SIC contract. In their euphoria from (a perceived) victory, the independent refiners did their best to exclude and ostracize Rockefeller, since he was the alleged (and actual) leader of the SIC. Little did they know at the time that the fall of the SIC wasn't going to slow down Rockefeller in the least. He already controlled 22 of the 26 refineries in the Oil Region, which meant that Rockefeller (pictured above in 1875) was in a position to keep making secret deals with the railroads. To Ida Tarbell, her father represented the "Noble Underdog" who was overwhelmed by the "Evil Empire" . . . and Rockefeller was her Darth Vader.

(When times were good for Franklin Tarbell, he moved his family to a better location. He purchased an abandoned hotel in a nearby oil ghost town for $600 ($10k today) and had it transported piece-by-piece to a plot of land he had just purchased . . . below, you see the new Tarbell home, which was completely reassembled in the early-1870s in Titusville, Pennsylvania)

For the rest of her life, Ida Tarbell viewed many Combinations as malevolent, and John D. Rockefeller was at the top of her "list". By 1868, Rockefeller owned the largest oil refinery in the world, and by 1877, Rockefeller controlled 90% of the nation's oil production. In 1882, Rockefeller established the Standard Oil Trust (his Oil Combination was made "legal"), which was designed to determine (fix) prices in the industry. Those that succumbed to Rockefeller were offered stock in the Standard Oil Trust, or the cash equivalent (the smart ones chose the stock option); Franklin Tarbell refused to join Rockefeller's Oil Combination, and he struggled financially for the rest of his life (he died in 1905). Ida Tarbell (pictured) would expose the shenanigans of Rockefeller in her 19 part series titled The History of the Standard Oil Company (1902 - 1904).

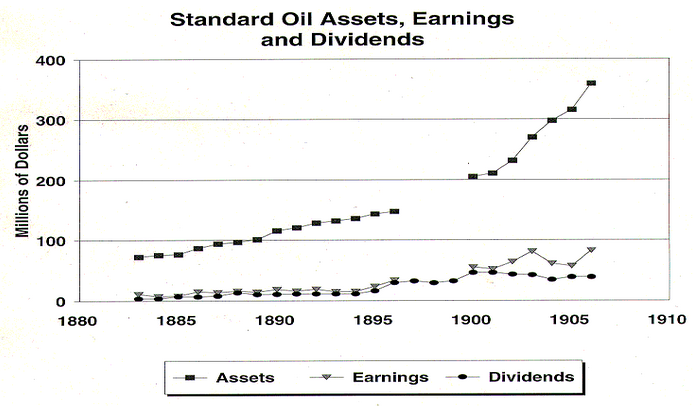

(Below: a visual representation of Rockefeller's wealth since

the inception of the Standard Oil Trust in 1882)

(Below: a visual representation of Rockefeller's wealth since

the inception of the Standard Oil Trust in 1882)