Source: Richard Brookhiser. James Madison (2011)

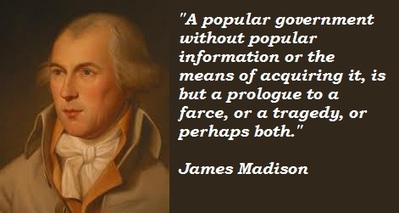

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison each served two terms as President. Jefferson's popularity plummeted by a large margin not long after he easily won re-election in 1804. By the time Jefferson left office, his popularity as a politician was at its lowest. In contrast, Madison barely won re-election in 1812, and his popularity nosedived even more halfway through his second term in office due to the War of 1812. However, in rallying his nation to what was seen as an American victory over the British, James Madison left office almost as popular as George Washington was during his first term, and far more popular than John Adams and his mentor, Thomas Jefferson. Usually, when a President's popularity falls off a precipice, there is very little chance to climb back into favor (e.g. Nixon, President George H.W. Bush in 1992). President James Madison found a way to do so as the first President to be in power during a major war.

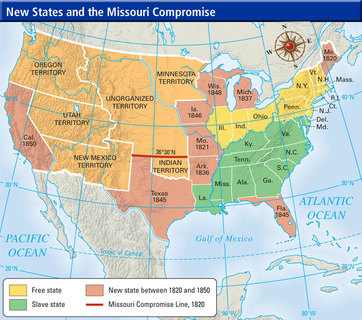

President Madison decided that it was time that the U.S. should at long last possess West Florida and New Orleans. In what would today undoubtedly be called a "Black Op", Madison authorized a clandestine operation against Spain that was headquartered in Baton Rouge and Mobile. Faced with such a popular uprising, Spain ceded the territory to the U.S. Government in 1810; the full potential of the Louisiana Territory could be realized, with the added bonus that Spanish influence was minimized in the Gulf Region.

In June, 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act, which lifted the embargo for U.S. ships heading to ports in Great Britain and France; Brookhiser referred to the act as "profitable dishonesty." As a result, the Atlantic was flooded with American merchant vessels heading to Great Britain. Great Britain, however, did not honor the act, and used the "Rule of 1756" to strangle American trade heading to Europe, and relations between the two nations chilled.

In the Spring of 1810, Macon's Bill #2 became law; the U.S. would trade with the nation that lifted their trade barriers first. The Republican doctrine of projecting American strength through trade never worked, and Madison was stunned to see that impact to U.S. trade was even worse than the Embargo of 1807. Napoleon offered to resume trade, but Madison chose to ignore the offer since there were too many obvious loopholes that would be to the disadvantage of the U.S. The British were beyond-incensed that the U.S. seemed to be negotiating with its European nemesis - slowly but surely, Madison was leading America to a war with Great Britain in a roundabout, sideways fashion.

In June, 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act, which lifted the embargo for U.S. ships heading to ports in Great Britain and France; Brookhiser referred to the act as "profitable dishonesty." As a result, the Atlantic was flooded with American merchant vessels heading to Great Britain. Great Britain, however, did not honor the act, and used the "Rule of 1756" to strangle American trade heading to Europe, and relations between the two nations chilled.

In the Spring of 1810, Macon's Bill #2 became law; the U.S. would trade with the nation that lifted their trade barriers first. The Republican doctrine of projecting American strength through trade never worked, and Madison was stunned to see that impact to U.S. trade was even worse than the Embargo of 1807. Napoleon offered to resume trade, but Madison chose to ignore the offer since there were too many obvious loopholes that would be to the disadvantage of the U.S. The British were beyond-incensed that the U.S. seemed to be negotiating with its European nemesis - slowly but surely, Madison was leading America to a war with Great Britain in a roundabout, sideways fashion.

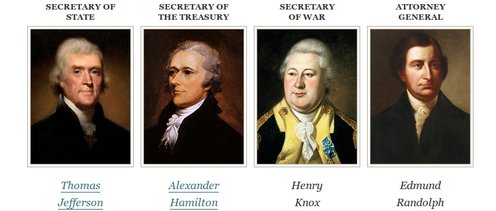

President Madison, unhappy with SecState Robert Smith's disunity and indiscretion, asked for his resignation, and replaced him with James Monroe - it was the creation of the "Virginia Dynasty." This was also the moment that Madison realized that he was the Chief Executive, no longer a legislator or a Cabinet member . . . but Madison was still too passive to be an effective President, and he still focused too much attention on intra-party matters.

In February, 1811, Congress voted to enforce the Non-Intercourse Act against Great Britain, which was a significant step towards war. Congress also wanted the National Bank to expire, contrary to SecTreas Albert Gallatin's advice and wishes. Ironically, it was also against Madison's wishes as well; he had come to see the Bank as Alexander Hamilton argued years before, an institution that was "Necessary and Proper." Madison was unwilling to lead the fight to renew the Bank's charter, however, and Gallatin (whose statue is in front of the Treasury Building) was left to fight the battle himself. The House voted to postpone their vote (which was decidedly anti-Bank) until the Senate conducted their vote. The Senate was deadlocked 17 - 17, but Vice-President George Clinton (NY; still sore that he didn't become President) broke the tie, and voted against the Bank. Madison would realize too late that if he had exercised any executive influence at all, the bank would have been saved, and would have been a very useful tool during the War of 1812 (imagine, the U.S. fought the War of 1812 without a National Bank!).

In February, 1811, Congress voted to enforce the Non-Intercourse Act against Great Britain, which was a significant step towards war. Congress also wanted the National Bank to expire, contrary to SecTreas Albert Gallatin's advice and wishes. Ironically, it was also against Madison's wishes as well; he had come to see the Bank as Alexander Hamilton argued years before, an institution that was "Necessary and Proper." Madison was unwilling to lead the fight to renew the Bank's charter, however, and Gallatin (whose statue is in front of the Treasury Building) was left to fight the battle himself. The House voted to postpone their vote (which was decidedly anti-Bank) until the Senate conducted their vote. The Senate was deadlocked 17 - 17, but Vice-President George Clinton (NY; still sore that he didn't become President) broke the tie, and voted against the Bank. Madison would realize too late that if he had exercised any executive influence at all, the bank would have been saved, and would have been a very useful tool during the War of 1812 (imagine, the U.S. fought the War of 1812 without a National Bank!).

The 12th Congress convened in 1811, and Henry Clay (KY) was voted Speaker of the House in his first term. For the first time in U.S. History, Clay used his position as Speaker to advance his personal and party's politics, and one of the things he most wanted to see was war with Great Britain (he believed it would benefit western states). There was "New Blood" in the 12th Congress, with John C. Calhoun (SC) on the Foreign Relations Committee, also pushing for war. These young "War Hawks" (Calhoun was only 29) consistently pressured Madison for war.

This Republican Congress was "stripping for a fight" with Britain, but the "War Hawks" were basically clueless that they were in no position to hold their own against a superpower. The revenue stream for the government trickled to virtually nothing, since there was no longer a National Bank which meant no regulation of the economy, no trade of note, and taxes were low. Their desire for war was high, but they were beyond-naive in grasping the true reality of what it would take to even have a chance at success in clashing with Great Britain.

By the Summer of 1812, Great Britain had not rescinded their trade barriers against the U.S., impressment of American sailors continued, as was British support for Native tribes on the frontier (e.g. the Tecumseh). On 1 June, Madison sent a war message to Congress, listing many grievances against the British; couched behind those grievances was a strong desire for national self-respect. After two-and-a-half weeks of debate, Congress voted 74-49 to declare war, while the Senate voted 19-13 (both houses largely along partisan lines). On 16 June, the British repealed their "Orders in Council", which eliminated most of the American grievances, but due to slow communication, there was no way either government could know of the actions of the other (and given the political climate in the U.S., one wonders if it would have made any difference).

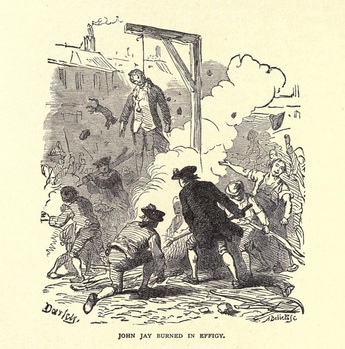

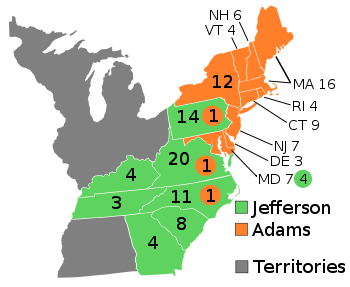

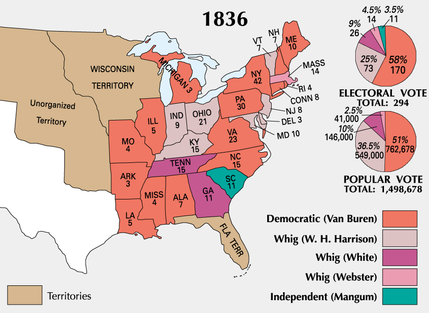

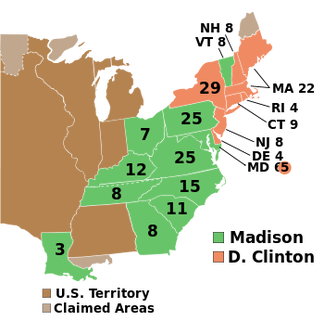

In the Election of 1812, President Madison won re-election, defeating the Federalist candidate DeWitt Clinton (who also received the support of anti-war Republicans), but only because he carried Pennsylvania. The Electoral tally was Madison, 128, and Clinton, 89, but if Clinton would have won Pennsylvania, the result would have been Clinton 114, and Madison, 103. It was the strongest showing of a Federalist candidate since President John Adams narrowly lost to Vice-President Thomas Jefferson in 1800.

This Republican Congress was "stripping for a fight" with Britain, but the "War Hawks" were basically clueless that they were in no position to hold their own against a superpower. The revenue stream for the government trickled to virtually nothing, since there was no longer a National Bank which meant no regulation of the economy, no trade of note, and taxes were low. Their desire for war was high, but they were beyond-naive in grasping the true reality of what it would take to even have a chance at success in clashing with Great Britain.

By the Summer of 1812, Great Britain had not rescinded their trade barriers against the U.S., impressment of American sailors continued, as was British support for Native tribes on the frontier (e.g. the Tecumseh). On 1 June, Madison sent a war message to Congress, listing many grievances against the British; couched behind those grievances was a strong desire for national self-respect. After two-and-a-half weeks of debate, Congress voted 74-49 to declare war, while the Senate voted 19-13 (both houses largely along partisan lines). On 16 June, the British repealed their "Orders in Council", which eliminated most of the American grievances, but due to slow communication, there was no way either government could know of the actions of the other (and given the political climate in the U.S., one wonders if it would have made any difference).

In the Election of 1812, President Madison won re-election, defeating the Federalist candidate DeWitt Clinton (who also received the support of anti-war Republicans), but only because he carried Pennsylvania. The Electoral tally was Madison, 128, and Clinton, 89, but if Clinton would have won Pennsylvania, the result would have been Clinton 114, and Madison, 103. It was the strongest showing of a Federalist candidate since President John Adams narrowly lost to Vice-President Thomas Jefferson in 1800.

The early results were in: so far, James Madison had failed as a war-time President, due mostly to the reality that he had the wrong people in charge of the wrong things at the wrong time. Madison had a chance to change all of that, but in 1814, Madison was unwilling to unleash his star, James Monroe, by naming him as acting SecWar while he was also SecState. So, Madison named John Armstrong as SecWar, whose qualifications for the position were lacking to most . . . the Republican party's disdain for all-things-military came back to haunt Madison early in the war (only Monroe and Gallatin were worthwhile Cabinet members).

As the British landed in force in Maryland, SecWar Armstrong believed that the British would leave Washington, D.C. alone, and instead attack Baltimore. Madison, after consulting Armstrong, allowed the decision to remain, and after the "Bladensburg Races", the British entered D.C. without any opposition. After this debacle, Madison named Monroe as acting SecWar in addition to his duties as SecState - that move provided real leadership when it was needed most. However, Madison had appointed Armstrong (and the feeble General William Winder at Bladensburg), plus numerous others that failed to make the grade. And yet, Armstrong was right on one thing - the British did indeed want Baltimore.

As the British landed in force in Maryland, SecWar Armstrong believed that the British would leave Washington, D.C. alone, and instead attack Baltimore. Madison, after consulting Armstrong, allowed the decision to remain, and after the "Bladensburg Races", the British entered D.C. without any opposition. After this debacle, Madison named Monroe as acting SecWar in addition to his duties as SecState - that move provided real leadership when it was needed most. However, Madison had appointed Armstrong (and the feeble General William Winder at Bladensburg), plus numerous others that failed to make the grade. And yet, Armstrong was right on one thing - the British did indeed want Baltimore.

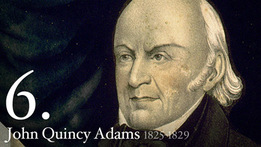

By the end of 1814, Madison and Washington, D.C. were no longer major players in the war. The focus shifted to negotiations in Ghent, Belgium (lead by John Quincy Adams), General Jackson in New Orleans, and the Federalist Convention in Hartford, Connecticut. Madison received the news of these three events in the following order, which lifted Madison's popularity as President to a level only surpassed by Washington in his first term.

First came word of Jackson's miraculous victory at New Orleans on 8 January, 1815 (The American army was outnumbered at least 10:1). Then came news from Ghent of a treaty that was signed in late-December, 1814, ending the war. And lastly, news of the desire of the New England Federalists in Hartford to secede from the Union. The sequence of events to the American public were processed like this: the miraculous victory in New Orleans meant the British have had enough of the war, so therefore we WON THE WAR, and those Federalists are traitors! For his remaining time as President, Madison was lauded as a hero by the vast majority, his party was once again united, and the Federalist party became extinct. Ironically, in March, 1816, Congress and President Madison authorized a Second National Bank of the United States.

First came word of Jackson's miraculous victory at New Orleans on 8 January, 1815 (The American army was outnumbered at least 10:1). Then came news from Ghent of a treaty that was signed in late-December, 1814, ending the war. And lastly, news of the desire of the New England Federalists in Hartford to secede from the Union. The sequence of events to the American public were processed like this: the miraculous victory in New Orleans meant the British have had enough of the war, so therefore we WON THE WAR, and those Federalists are traitors! For his remaining time as President, Madison was lauded as a hero by the vast majority, his party was once again united, and the Federalist party became extinct. Ironically, in March, 1816, Congress and President Madison authorized a Second National Bank of the United States.

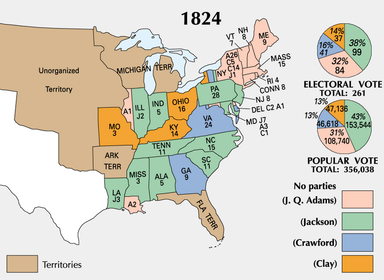

As America basked in its newfound total independence from Great Britain (political, social and economic), there was a Presidential Election in 1816. James Monroe edged William Crawford (GA) for the Republican nomination, and then cruised to the White House by soundly defeating the token Federalist candidate Rufus King (Electoral Vote: Monroe 183, King 34).

James Madison refused to be a spectator to his own Presidency towards the end of his second term, as Thomas Jefferson had decided to do. For example, on 3 March, 1817 (his last day in office) Madison vetoed a bill providing federal money for roads and canals. While Madison wanted improved transportation for expansion, he viewed federal spending for roads and canals as unconstitutional - it was a matter reserved for the states (Monroe would do the same with his famous veto of the Cumberland Road).

In the years after his Presidency, Madison refused to publish his notes from the Constitutional Convention in 1787 as long as he was alive; he thought the impact of their release would be greater after his death (historians treasured his notes, but ironically the general public didn't embrace his account nearly as much at that time). Madison lived for almost twenty years as an ex-President. His most notable contribution was during the Nullification Crisis in the early-1830s, when he joined Jackson (a man he truly did not like or trust) in his pro-Union stance against those that wanted to secede.

James Madison was the last Framer of the Constitution to die (he even outlived James Monroe, who died on 4 July five years to the day after J. Adams and Jefferson). Madison died on 28 June, 1836; his doctors offered to extend his life to 4 July so he could join John Adams, Jefferson, and Monroe, but he politely-yet-firmly declined.

James Madison refused to be a spectator to his own Presidency towards the end of his second term, as Thomas Jefferson had decided to do. For example, on 3 March, 1817 (his last day in office) Madison vetoed a bill providing federal money for roads and canals. While Madison wanted improved transportation for expansion, he viewed federal spending for roads and canals as unconstitutional - it was a matter reserved for the states (Monroe would do the same with his famous veto of the Cumberland Road).

In the years after his Presidency, Madison refused to publish his notes from the Constitutional Convention in 1787 as long as he was alive; he thought the impact of their release would be greater after his death (historians treasured his notes, but ironically the general public didn't embrace his account nearly as much at that time). Madison lived for almost twenty years as an ex-President. His most notable contribution was during the Nullification Crisis in the early-1830s, when he joined Jackson (a man he truly did not like or trust) in his pro-Union stance against those that wanted to secede.

James Madison was the last Framer of the Constitution to die (he even outlived James Monroe, who died on 4 July five years to the day after J. Adams and Jefferson). Madison died on 28 June, 1836; his doctors offered to extend his life to 4 July so he could join John Adams, Jefferson, and Monroe, but he politely-yet-firmly declined.

James Madison accomplished something that the vast majority of two-term Presidents could not claim. Not only did Madison's second term surpass his first, but Madison reached his greatest popularity as he exited office after eight years. Think of the two-term Presidents in our history that did not have the "Madison Exit": Jefferson, Grant, Wilson (LBJ, Nixon), Reagan, Clinton, and Bush ("The Younger"); even Washington and Monroe didn't exit office at the same level of popularity as Madison.

The only two-term Presidents that I can think of whose popularity remained high after eight years in office were Theodore Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower; even FDR suffered a drop in popularity and effectiveness during his second term. There was no doubt that Madison benefited from luck and timing, but he also made crucial decisions that not only buttressed his popularity, but led the U.S. to a favorable end to its first major war under the Constitution.

(Below: The Presidency of James Madison, from the History Channel's "The Presidents")

The only two-term Presidents that I can think of whose popularity remained high after eight years in office were Theodore Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower; even FDR suffered a drop in popularity and effectiveness during his second term. There was no doubt that Madison benefited from luck and timing, but he also made crucial decisions that not only buttressed his popularity, but led the U.S. to a favorable end to its first major war under the Constitution.

(Below: The Presidency of James Madison, from the History Channel's "The Presidents")