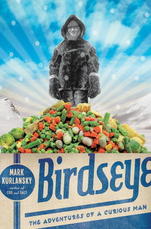

Source: Mark Kurlansky. Birdseye: The Adventures of a Curious Man (2012)

Clarence Birdseye was a man who observed how things worked, and figured out how to make them work better. Birdseye was also an adventurer, even though he looked like someone that would be more at home in a library. While his innovations / inventions were all mechanical (never electronic), he made a huge impact in US History, most famously developing the frozen food industry. Birdseye risked his life to help people in Montana, and then on the Labrador Coast in Canada, all the while trying all sorts of different, and many times exotic, food. It was during those years as an adventurer in Canada that he figured out the best method to freeze food.

Clarence Frank Birdseye II was born in Brooklyn, NY on 9 December, 1886. At the turn of the century, Brooklyn was the third-largest city in America, and its dense urban population was possible due to the technology of refrigeration. Hundreds of thousands of people produced no food, but bought and stored food in ice-boxes; there was no other place in the world that used as much ice as the citizens of New York City and it surrounding boroughs . . . it was so common that they took the technology for granted.

Birdseye grew up in an inventor's culture in America that valued practical and commercial applications; in Europe, the approach of inventors was far more theoretical. In the US, a successful inventor was one that founded an industry, such as Edison and electricity, or Eastman and film photography. Birdseye also grew up during the "Age of Extermination"; he couldn't remember a time when he didn't love to hunt. He romanticized the West, and his first hero was Buffalo Bill Cody.

Birdseye grew up in an inventor's culture in America that valued practical and commercial applications; in Europe, the approach of inventors was far more theoretical. In the US, a successful inventor was one that founded an industry, such as Edison and electricity, or Eastman and film photography. Birdseye also grew up during the "Age of Extermination"; he couldn't remember a time when he didn't love to hunt. He romanticized the West, and his first hero was Buffalo Bill Cody.

Birdseye was a born Naturalist as well; he was happiest as a kid when wandering around Wyndiecote (an isolated wooded area) in Long Island. He bought a single-gauge shotgun at the age of ten by trapping twelve muskrat, and sending them to a buyer in Great Britain, earning the equivalent of $250 in today's money. He used the shotgun and learned how to preserve and stuff the animals he shot by reading and asking questions; even at that age, Birdseye was someone that everyone liked, and they wanted to answer his questions.

By the time he became a teenager, Birdseye was fascinated with science. During college, he was so curious about insects that he was called "Bugs" by his peers (He was also called "Spots", which he didn't mind as much). Birdseye didn't like the nickname "Bugs", and he was in a tough situation, in that he was an extrovert, but he kept to himself to avoid ridicule. In 1908, family financial troubles forced Birdseye to drop out of Amherst College in Massachusetts; he would never again pursue formal education. Very soon thereafter, he went West, looking for adventure while he was still young.

By the time he became a teenager, Birdseye was fascinated with science. During college, he was so curious about insects that he was called "Bugs" by his peers (He was also called "Spots", which he didn't mind as much). Birdseye didn't like the nickname "Bugs", and he was in a tough situation, in that he was an extrovert, but he kept to himself to avoid ridicule. In 1908, family financial troubles forced Birdseye to drop out of Amherst College in Massachusetts; he would never again pursue formal education. Very soon thereafter, he went West, looking for adventure while he was still young.

Birdseye went to Arizona and New Mexico in 1908, eventually working for the U.S. Biological Survey, which was then part of the Agriculture Dept. His job was to exterminate "nuisance" animals for the area ranchers/farmers. Birdseye used steel traps to kill wolves and coyotes; once trapped, the animals starved to death - it was even then a controversial method.

Those in the Survey knew that these animals didn't really present a threat to livestock, but they continued anyway, since that was what the Agriculture Dept. wanted.

Birdseye figured out how to make money with coyote furs by paying Natives fifty cents, which was twice their asking price. Once he had those furs, he sent them to NYC, and they were sold for $1.25 each. When he found something exotic, he always wondered what it would taste like, and which was the best method to cook the animal or plant. Birdseye was astounded to discover the reliance (addiction?) of Westerners to canned food from the East, but as it turned out, he loved the canned food as well. In 1910, Birdseye linked up part-time with the National Geographic Society (formed in 1888), and he explored, investigated new ideas, took photos, and didn't have to worry about politics . . . it was everything Birdseye loved.

Those in the Survey knew that these animals didn't really present a threat to livestock, but they continued anyway, since that was what the Agriculture Dept. wanted.

Birdseye figured out how to make money with coyote furs by paying Natives fifty cents, which was twice their asking price. Once he had those furs, he sent them to NYC, and they were sold for $1.25 each. When he found something exotic, he always wondered what it would taste like, and which was the best method to cook the animal or plant. Birdseye was astounded to discover the reliance (addiction?) of Westerners to canned food from the East, but as it turned out, he loved the canned food as well. In 1910, Birdseye linked up part-time with the National Geographic Society (formed in 1888), and he explored, investigated new ideas, took photos, and didn't have to worry about politics . . . it was everything Birdseye loved.

During the Spring/Summer of 1910, Birdseye was in Montana, collecting ticks as part of a

medical project trying to figure out the cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. He was allowed unrestricted hunting of wildlife; in other words, there wasn't any limit for Birdseye in terms of shooting animals. It turned out that this job was VERY dangerous - it was the first formal scientific study of the disease, which killed 20% of those infected. The disease appeared and spread in the 1870s when the lumber industry exploded in the region. In 1889, a tick was discovered on a patient, and years later it was determined that Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever was caused by being bitten by a tick.

Among the many new fields of study that burst upon the scene at the turn of the century was Entomology; in 1909, "Medical Entomology" took root in the Bitterroot Region of Montana, providing the first comprehensive study of ticks. The medical profession at large, as well as the locals, scoffed at these "Bug People", believing that there was no way ticks were the cause of a disease that was so deadly. A twenty-three year old Birdseye was among those that the Biological Survey sent to Montana in 1910. Few were willing to go since it was so dangerous in the field, especially in the Bitterroot Mountains. Birdseye killed about every type of mammal in the region, getting samples of ticks afterwards. As a result of Birdseye's work with two other men, it was proven that ticks caused the disease. Ticks fed on small animals, and worked their way up to larger ones, meaning it was a two-year cycle. It was determined that if a tick fed on a person for a few hours, it was very likely that a person would contract the disease.

Ranchers refused to recognize the findings, due to the cost of using the recommended repellent. But in the end, there was no real solution other than to follow the Biological Survey's recommendations, since the source was identified, and a repellent developed; the disease vanished in the area as a result. But the dangerous work had to continue in 1911, and Birdseye returned to Montana; he eventually recommended that small animals, especially gophers, should be exterminated, leaving the large animals alone. What makes his recommendation somewhat ironic is that the Biological Survey eventually became the Fish & Wildlife Service, whose mission is to regulate protected environments.

medical project trying to figure out the cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. He was allowed unrestricted hunting of wildlife; in other words, there wasn't any limit for Birdseye in terms of shooting animals. It turned out that this job was VERY dangerous - it was the first formal scientific study of the disease, which killed 20% of those infected. The disease appeared and spread in the 1870s when the lumber industry exploded in the region. In 1889, a tick was discovered on a patient, and years later it was determined that Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever was caused by being bitten by a tick.

Among the many new fields of study that burst upon the scene at the turn of the century was Entomology; in 1909, "Medical Entomology" took root in the Bitterroot Region of Montana, providing the first comprehensive study of ticks. The medical profession at large, as well as the locals, scoffed at these "Bug People", believing that there was no way ticks were the cause of a disease that was so deadly. A twenty-three year old Birdseye was among those that the Biological Survey sent to Montana in 1910. Few were willing to go since it was so dangerous in the field, especially in the Bitterroot Mountains. Birdseye killed about every type of mammal in the region, getting samples of ticks afterwards. As a result of Birdseye's work with two other men, it was proven that ticks caused the disease. Ticks fed on small animals, and worked their way up to larger ones, meaning it was a two-year cycle. It was determined that if a tick fed on a person for a few hours, it was very likely that a person would contract the disease.

Ranchers refused to recognize the findings, due to the cost of using the recommended repellent. But in the end, there was no real solution other than to follow the Biological Survey's recommendations, since the source was identified, and a repellent developed; the disease vanished in the area as a result. But the dangerous work had to continue in 1911, and Birdseye returned to Montana; he eventually recommended that small animals, especially gophers, should be exterminated, leaving the large animals alone. What makes his recommendation somewhat ironic is that the Biological Survey eventually became the Fish & Wildlife Service, whose mission is to regulate protected environments.

The key moment in Birdseye's life occurred when he decided to go to the Labrador Coast in Canada. In 1912, Labrador was a wild and uncharted wilderness with ports that froze in the winter. People in Labrador could hunt and fish (except in the winter), but they had to import their fruits and vegetables. Birdseye joined the legendary Dr. Wilfred Grenfell's medical missions to assist fishermen in Labrador; by then, Grenfell was staying in Labrador during the long, brutal winters. In Grenfell, Birdseye found a fellow adventurer (twice his age) that also wanted to help people. Birdseye decided that while he was helping people in Labrador, he would also focus his attention to try and apply scientific knowledge in order to pursue an economic opportunity. So, Birdseye decided to trap silver foxes, and send them to the U.S. as breeding stock for starting a fur company.

Harris Hammond of Gloucester, Massachusetts, backed Birdseye with $750 ($18k today); it was the beginning of the Harris & Birdseye Fur Company. Birdseye procured foxes by traveling by dogsled weeks at a time; he learned about foxes and survival in the winter by asking questions of anyone he encountered. He specialized in sucking volumes of information from those that were even reluctant to provide answers. It was at about this time that Birdseye changed his first name to Bob - probably because Bob is more approachable than Clarence.

(Below: A brief biography of Dr. Wilfred Grenfell)

Harris Hammond of Gloucester, Massachusetts, backed Birdseye with $750 ($18k today); it was the beginning of the Harris & Birdseye Fur Company. Birdseye procured foxes by traveling by dogsled weeks at a time; he learned about foxes and survival in the winter by asking questions of anyone he encountered. He specialized in sucking volumes of information from those that were even reluctant to provide answers. It was at about this time that Birdseye changed his first name to Bob - probably because Bob is more approachable than Clarence.

(Below: A brief biography of Dr. Wilfred Grenfell)

Birdseye was an expert hunter, and he became an expert fisherman, as well as a de facto Corpsman acting on behalf of Dr. Grenfell. He learned as much as he could about wildlife in Labrador, whether an animal was alive or dead. He was also obsessed with food in Labrador; he had an endlessly curious palette, and the more exotic the food, the better (he especially loved seal meat).

In 1914, the fur industry collapsed in Europe and NYC, but Birdseye saw opportunity in America-at-large. He killed his current number of silver foxes, and purchased as many other furs as possible at the deflated prices due to the collapse of the industry after being staked $8000 ($185k today). He froze the small animals in snow for shipment, and in essence, he cornered the fur market in Labrador. In 1915, Birdseye went back home to marry Eleanor (they had been putting off marriage for awhile); he was twenty-nine years old. As it turned out, Birdseye would get his best ideas after marrying Eleanor, since he was thinking beyond himself and his needs.

Birdseye (with Eleanor) went back to Labrador, and built a solid, three-room house, which would protect them in the long winters. He wanted his family (now with son Kellogg) to eat well, and he also needed to learn how to preserve food to feed his new silver foxes. His food concerns were of an immediate nature; he wasn't thinking (yet) of launching a new food industry.

In 1914, the fur industry collapsed in Europe and NYC, but Birdseye saw opportunity in America-at-large. He killed his current number of silver foxes, and purchased as many other furs as possible at the deflated prices due to the collapse of the industry after being staked $8000 ($185k today). He froze the small animals in snow for shipment, and in essence, he cornered the fur market in Labrador. In 1915, Birdseye went back home to marry Eleanor (they had been putting off marriage for awhile); he was twenty-nine years old. As it turned out, Birdseye would get his best ideas after marrying Eleanor, since he was thinking beyond himself and his needs.

Birdseye (with Eleanor) went back to Labrador, and built a solid, three-room house, which would protect them in the long winters. He wanted his family (now with son Kellogg) to eat well, and he also needed to learn how to preserve food to feed his new silver foxes. His food concerns were of an immediate nature; he wasn't thinking (yet) of launching a new food industry.

In the Winter of 1916-1917, Birdseye had a full larder, filled with fruits and vegetables; but he needed a way to keep them fresh and edible. It was at this point in his life he became serious about the science of freezing food. Freezing food was nothing new in the mid-1910s, but very few people knew about the "Laws of Crystallization". As a result, when frozen food was thawed, it was pretty mushy, icky, and awful, and no one liked eating it at all. But, most frozen food in Labrador, when thawed, was not just adequate, it was close to fresh.

Birdseye spent months trying to figure out the mystery of the "Live Frozen Fish" of the area Natives; the fish that these Natives had frozen actually swam around normally when thawed. One of the things Birdseye noticed was that food wasn't as good if it was frozen early or late in the winter . . . finally he made the connection. When food was frozen instantly (e.g. when winter was at its coldest), it stayed fresh when it was thawed. He knew that it had something to do with the size of the crystals; salting food (the opposite of freezing) required large crystals, while freezing needed very small crystals . . . when food "Quick-Freezes", crystallization is at its smallest.

In 1917, Birdseye went back to the U.S.; freezing food was on the "back-burner" in his mind. He started work for the U.S. Fisheries, trying to solve the problem of how to get fresh fish to far-away markets in good condition. If he could figure that out, people would eat more fish, and the industry would expand, as would his reputation as a problem-solver. After numerous failures, he remembered "Quick-Freezing" in Labrador.

Birdseye spent months trying to figure out the mystery of the "Live Frozen Fish" of the area Natives; the fish that these Natives had frozen actually swam around normally when thawed. One of the things Birdseye noticed was that food wasn't as good if it was frozen early or late in the winter . . . finally he made the connection. When food was frozen instantly (e.g. when winter was at its coldest), it stayed fresh when it was thawed. He knew that it had something to do with the size of the crystals; salting food (the opposite of freezing) required large crystals, while freezing needed very small crystals . . . when food "Quick-Freezes", crystallization is at its smallest.

In 1917, Birdseye went back to the U.S.; freezing food was on the "back-burner" in his mind. He started work for the U.S. Fisheries, trying to solve the problem of how to get fresh fish to far-away markets in good condition. If he could figure that out, people would eat more fish, and the industry would expand, as would his reputation as a problem-solver. After numerous failures, he remembered "Quick-Freezing" in Labrador.

In 1922, Birdseye left his job, and convinced an ice cream company to let him experiment in one of their freezer areas. Little did he know that America would be the birthplace of frozen food, while Europe would focus on smoking, salting, and canning food. What eventually aided Birdseye as well was that his efforts coincided with the development of electric refrigerators and freezers. But the bulk of refrigeration/freezing in 1922 still meant ice, and like electricity, America had "Democratized" ice . . . it was for everyone (in Europe, ice was still for the rich). Interestingly, Americans had to get "used" to artificial (man-made) ice, which occurred in 1890, due to an extraordinarily moderate winter . . . artificial ice had become the norm by the early-1920s.

Frozen food already existed in the U.S., but most Americans gave it "Two Thumbs Down" for quality. Various methods of freezing food fast had been in tried for years in the fledgling frozen food industry. One method was to fast-freeze fish in salt and ice, which was sold in 1915, when Birdseye was in Labrador. The main reason why Birdseye didn't pursue frozen food earlier than he did was due to its horrible reputation with the American consumer.

Frozen food already existed in the U.S., but most Americans gave it "Two Thumbs Down" for quality. Various methods of freezing food fast had been in tried for years in the fledgling frozen food industry. One method was to fast-freeze fish in salt and ice, which was sold in 1915, when Birdseye was in Labrador. The main reason why Birdseye didn't pursue frozen food earlier than he did was due to its horrible reputation with the American consumer.

In 1923, Birdseye created a company called Birdseye Seafoods in NYC; he tried chilling fish in fiberboard boxes, and . . . ICK! . . . At this point, he specifically started to apply his knowledge from Labrador. Fast-freezing had been around awhile, but no one had tried freezing food on a large scale. Birdseye estimated that meat/fish wasn't truly frozen unless it reached minus ninety-six degrees Fahrenheit, yet existing commercial freezers only went to twenty-five

degrees Fahrenheit.

Birdseye found that if he quickly reached twenty-two degrees Fahrenheit as fast as possible, small crystals formed around the food very quickly. He also found that smaller amounts of food froze (crystallized) faster and better than larger amounts (he would eventually freeze peas one at a time). In 1924, Birdseye took out a patent on his process, and by freezing one fish at a time, he had frozen fish on the market that same year. Despite all his advances and successes in the science of frozen food, Birdseye Seafoods went broke within a year; he just couldn't overcome the negative consumer opinions towards frozen food.

degrees Fahrenheit.

Birdseye found that if he quickly reached twenty-two degrees Fahrenheit as fast as possible, small crystals formed around the food very quickly. He also found that smaller amounts of food froze (crystallized) faster and better than larger amounts (he would eventually freeze peas one at a time). In 1924, Birdseye took out a patent on his process, and by freezing one fish at a time, he had frozen fish on the market that same year. Despite all his advances and successes in the science of frozen food, Birdseye Seafoods went broke within a year; he just couldn't overcome the negative consumer opinions towards frozen food.

Bob Birdseye had no way to realize that he was very close to a scientific and financial breakthrough in the world of frozen food. Before the end of the 1920s, he would create a company that would go on to make a bit of a mark in American history . . . General Foods.