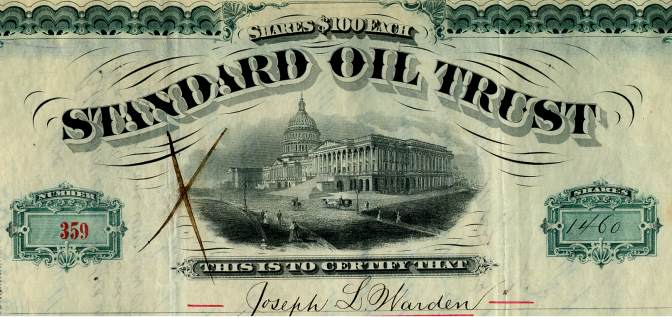

To form a "Trust", the companies that were merged into a Combination reorganized their shares in the Stock Market, and created an "Independent" Board that would then operate the colossus. The goal was to crush competition to maximize profits, and few were better at the Combination Game than John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, that controlled 90% of the oil industry by the time TR became President in 1901.

Potential profits were so great, and many Combinations were formed in many industries, that Congress passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890. But that law wasn't enforced by Presidents Harrison, Cleveland, and McKinley, because consumers largely benefited somehow / someway from Combinations. For example, Standard Oil refined and sold the safest (and very affordable) kerosene on the market; there were Combinations for virtually every consumer good, including a Combination for chewing gum. TR was ideologically conservative towards Combinations, believing that the overall benefits outweighed the costs . . . 65% of the overall wealth in the US was attributed to Combinations.

The resistance by the Coal Combination to the growing United Mine Workers was profound; they did have at least tacit public support since the Haymarket Square Riot in Chicago (1886) convinced most of the public that Labor was the main antagonist. TR's support of Labor had severely dimmed as a result of the Haymarket Riot, but on the other hand, he understood more than most that Combinations (especially in transportation and industry) consumed the resources as if they were a swarm of locusts. Conservation, a term that by 1901 had become fashionable and accepted by many Americans, meant not only should natural resources be preserved, but Combinations should be prevented from destroying those resources.

In situations involving extreme points-of-view, TR always wanted to find the center. TR's speeches on the "Coal Crisis" equivocated, and editorials on both sides of the issue harshly criticized the new President. However, mixed in with the equivocations was TR's desire for the national government to regulate Combinations.

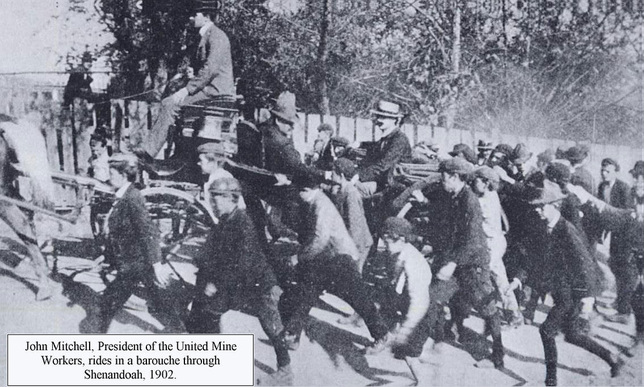

(Pictured: UMW leader John Mitchell leading miners in a protest during the lockout)

Demand for coal skyrocketed with the continued Capital v. Labor struggle in Pennsylvania, and the approaching winter. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (MA); one of TR's closest friends and advisors, demanded that TR do something to end the crisis; TR responded that unless the Governor of Pennsylvania asked for assistance, the federal government's hands were tied. TR suspected that the real issue was that the Coal Combination wanted to save face in the public arena, as well as with other Combinations . . . the mine owners didn't want to acquiesce to the government, or even a single politician, in the public arena.

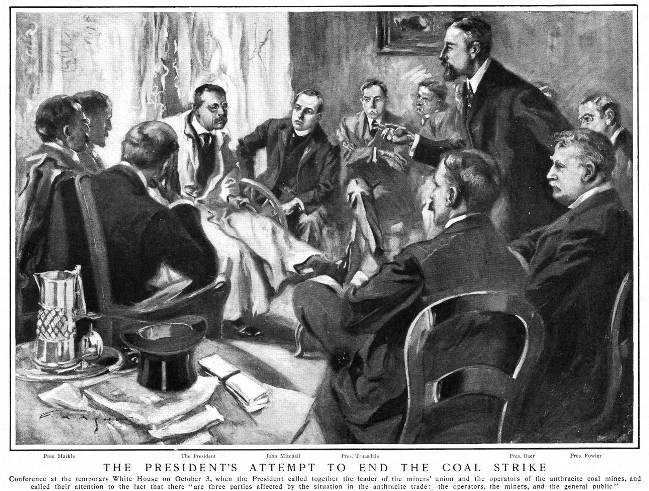

Both sides in the crisis had made it clear in the media that they would not be receptive to any interference from state or federal governments. So TR sent out duplicate telegrams to the Coal Combination owners and Labor in the guise of "Presidential Invitations". which was in reality a polite Presidential Order. Shockingly, both parties agreed to meet in the same room with President Roosevelt. TR met with the leaders of both parties still confined to a wheelchair, since he was still convalescing from a near-fatal car-trolley accident some weeks prior (he was thrown from the car over twenty feet, landing flat on his face, and his right shin needed two operations)

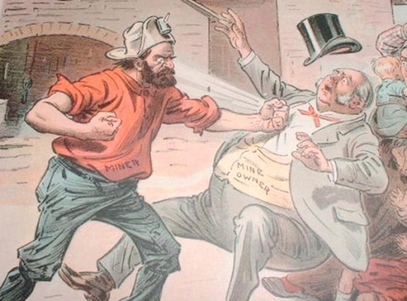

(Political Cartoon of Labor "Striking" Capital)

The representatives of the Coal Combination didn't think that UMW leader Mitchell should be part of the assembled party, since he was part of the bituminous (soft) coal industry, not anthracite (hard) coal. Nonetheless, TR gave all 14 assembled his written views, and adjourned the meeting until 3 pm; the Combination representatives spent the adjournment fuming.

The Combination told TR that the 10% wage hike he was suggesting would threaten their profitability (which was true); what they really wanted from TR was protection from the federal government against the striking miners in order to get "scabs" (replacement workers) into the mines. The Anthracite Coal Combination representatives knew that bituminous coal was far more plentiful, and if the flow of anthracite coal continued to be interrupted, they could be out of business.

When the meeting resumed at 3 pm, TR asked the Combination reps if Mitchell's (UMW) proposal for a 3rd-Party mediation to the dispute was acceptable - the Combination reps immediately stated that it was unacceptable. The media lauded TR for trying to end the crisis, and excoriated both Capital and Labor for their continued intransigence.

was the perfect choice to find a solution to the Coal Crisis.

TR sent Root to see Morgan, after he briefed both Root and Attorney General Philander Knox that he was about ready to use the Army; not since April, 1861, had the U.S. been in such a potential state of affairs. Rumors of a General Strike (workers striking across many industries) were pervasive, and TR gave orders to General Schofield that he only answered to the President, and if he was ordered to go to Pennsylvania, he was to use overwhelming force to quickly end the crisis.

On 13 October, 1902, SecWar Root and J.P. Morgan met with TR; Morgan stated that Capital tacitly acknowledged the supremacy of the federal government. Morgan also broached the subject of the Coal Combination's wish of who would be a member of the Commission of Inquiry - under no circumstances did they want a member of Labor to be on the commission. Since the Coal Combination expressed support of the inquiry, with one major demand, TR felt that he had quite a bit of latitude in how he could proceed.

"Corsair Agreement" officially announced the Commission of Inquiry to end the Coal Crisis, but still unresolved was the question of who would be on the commission. Combination reps finally agreed to a Labor representative on the Committee of Inquiry if he wasn't officially identified as a representative of Labor. To TR, this was a case of "Tweedledum v. Tweedledee", but he pounced on the opening.

The Combination reps agreed to a Labor leader being on the Committee of Inquiry if he was publicly identified as a SOCIOLOGIST. Soon, all seven members of the Committee of Inquiry were in place, and the flow of anthracite coal once again resumed, ending the crisis. TR was universally lauded as the hero that ended the potential catastrophe (which was to a large extent true), and was portrayed as the first President to stand up to a Combination (which was true). TR's "Litmus Test" for when to challenge a Combination was to determine of the "Public Good" was threatened; even before the Coal Crisis, TR was in the process of challenging J.P. Morgan's "Northern Securities" Railroad Combination proposal.