Source: Lynne Olson. Those Angry Days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and

America's Fight Over World War II, 1939 - 1941 (2013)

America's Fight Over World War II, 1939 - 1941 (2013)

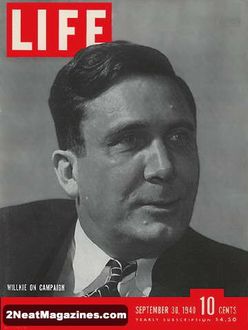

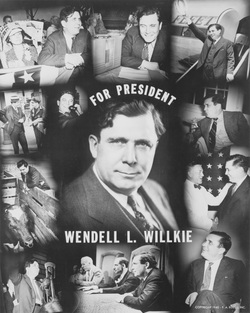

Wendell Willkie's rise to political prominence in 1940 was swift and largely unexpected. He was an Internationalist, which meant that he strongly favored direct U.S. assistance to a beleaguered Great Britain. In essence, the Fall of France increased the likelihood that Willkie could be nominated as the Republican Presidential candidate.

At the dawn of the Great Depression, Willkie was not a politician, he was in charge of the largest Southern Electric Utility, Commonwealth & Southern; and the Tennessee Valley Authority entered his landscape. Commonwealth & Southern was "crowded out" of the utility marketplace by the federal government, and Willkie went on the attack against the New Deal, and FDR (despite being "crowded out", Willkie came out a winner, in that the government purchased Commonwealth & Southern for $78.6m). Like Lincoln in 1858, Willkie became a nationally known-and-respected political figure as a result of a high-profile debate. He became a voice for moderate middle class Americans, especially businessmen that believed the federal government had become too involved in their affairs.

At the dawn of the Great Depression, Willkie was not a politician, he was in charge of the largest Southern Electric Utility, Commonwealth & Southern; and the Tennessee Valley Authority entered his landscape. Commonwealth & Southern was "crowded out" of the utility marketplace by the federal government, and Willkie went on the attack against the New Deal, and FDR (despite being "crowded out", Willkie came out a winner, in that the government purchased Commonwealth & Southern for $78.6m). Like Lincoln in 1858, Willkie became a nationally known-and-respected political figure as a result of a high-profile debate. He became a voice for moderate middle class Americans, especially businessmen that believed the federal government had become too involved in their affairs.

Willkie, a native from Indiana, was a Democrat until 1939. Willkie changed his political party affiliation in part to falling in love with NYC (and with Irita Van Doren, a prominent book editor for the New York Herald Tribune; although he was married), but mostly due to events that unfolded in the War in Europe. The Herald formally endorsed Willkie for the Republican nomination over Thomas Dewey, who most everyone believed had already secured the nomination.

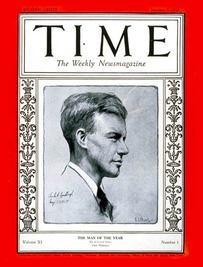

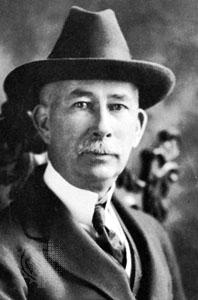

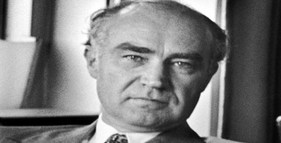

Willkie's NYC connections insured that he was introduced to many more East Coast Elites that could help him in his quest for the nomination. Magazine articles in Fortune magazine that profiled Willkie, as well as the nightmarish War in Europe, led to petition drives on Willkie's behalf. Those petition drives increased Willkie's profile and popularity in the rest of the nation. When Henry Luce (pictured), the owner of Time, Life, and Fortune magazines, committed to Willkie, those magazines shifted to flat-out advocacy for his nomination. Willkie had become so popular in the Midwest that he embarked on a public speaking tour; despite the increased popularity and support, Willkie was still a long shot to win the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in June, 1940.

Willkie's NYC connections insured that he was introduced to many more East Coast Elites that could help him in his quest for the nomination. Magazine articles in Fortune magazine that profiled Willkie, as well as the nightmarish War in Europe, led to petition drives on Willkie's behalf. Those petition drives increased Willkie's profile and popularity in the rest of the nation. When Henry Luce (pictured), the owner of Time, Life, and Fortune magazines, committed to Willkie, those magazines shifted to flat-out advocacy for his nomination. Willkie had become so popular in the Midwest that he embarked on a public speaking tour; despite the increased popularity and support, Willkie was still a long shot to win the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in June, 1940.

The gavel opened the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia on 24 June, 1940, one week after the Fall of France. Willkie had called for immediate U.S. aid to Britain, oftentimes publicly stating that he was in full agreement with FDR. To Republican "Old Guard" Isolationists, Willkie was a vision from political hell. And since the "Old Guard" ran the party machinery, the battle for the nomination appeared to be between the Isolationist candidates Thomas Dewey (NY) or Robert A. Taft (OH; President Taft's oldest son).

Willkie was formally nominated on 26 June, 1940; the chants from the delegates on the floor of "We Want Willkie" became deafening. The convention became a showdown between Isolationists and Internationalists as to the role the U.S. should play in the War in Europe. The results of the first ballot were: Dewey 360, Taft 189, and Willkie 105; Dewey didn't have the necessary majority. As successive ballots were conducted, Willkie gained more-and-more delegates. After eight hours of balloting, the "Miracle in Philadelphia" occurred at 1:15 am when Willkie secured the nomination over the efforts of the party's "Old Guard" to block his victory. The Republican platform illustrated the ideological divide, in that it was an uneasy compromise between Isolationist and Internationalist points-of-view concerning America's role in European War.

The British Ambassador to the U.S., Phillip Kerr (a.k.a. Lord Lothian; who was VERY popular in America), cabled Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Britain was guaranteed to have a "friendly" U.S. President, no matter the result in November.

Willkie was formally nominated on 26 June, 1940; the chants from the delegates on the floor of "We Want Willkie" became deafening. The convention became a showdown between Isolationists and Internationalists as to the role the U.S. should play in the War in Europe. The results of the first ballot were: Dewey 360, Taft 189, and Willkie 105; Dewey didn't have the necessary majority. As successive ballots were conducted, Willkie gained more-and-more delegates. After eight hours of balloting, the "Miracle in Philadelphia" occurred at 1:15 am when Willkie secured the nomination over the efforts of the party's "Old Guard" to block his victory. The Republican platform illustrated the ideological divide, in that it was an uneasy compromise between Isolationist and Internationalist points-of-view concerning America's role in European War.

The British Ambassador to the U.S., Phillip Kerr (a.k.a. Lord Lothian; who was VERY popular in America), cabled Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Britain was guaranteed to have a "friendly" U.S. President, no matter the result in November.

Hitler's invasion of Western Europe helped the Democrats far more than the Republicans. FDR had been losing serious political momentum during his disastrous second term in office, but Hitler brought FDR back to popularity within the party (the desire for a Commander-in-Chief became paramount). To be even more clear, FDR was politically dead-in-the-water before Germany invaded Poland on 1 September, 1939: Democratic Party leaders were not even planning on nominating the two-term President at the following year's convention . . . Hitler's actions on Europe saved FDR's political fortunes.

FDR made up his mind to pursue a third term just before France fell to the Nazis in June, 1940. FDR (in a maneuver that would have made Jefferson proud), refused to promote himself for the Democratic nomination; others would have to do so.

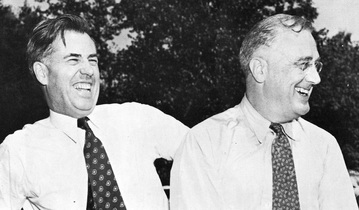

The Democratic National Convention started on 15 July, 1940, in Chicago . . . and it started out in listless fashion - there wasn't any "We Want FDR" chants from the floor. FDR's powerful supporters started the chant in support of FDR after the nominations were made with the infamous "Sewer Call" (the man in charge of building maintenance was below the floor, with a microphone and a deep sonorous voice; he started the "We Want FDR" chant). FDR wanted to be nominated by acclamation, but a roll call vote took place; FDR easily won the nomination. The delegates felt that they had been manipulated, but they believed that at least they would be able to select FDR's Vice-Presidential candidate; little did they know that FDR was all-in on his SecAg, Henry Wallace (to FDR's right).

FDR made up his mind to pursue a third term just before France fell to the Nazis in June, 1940. FDR (in a maneuver that would have made Jefferson proud), refused to promote himself for the Democratic nomination; others would have to do so.

The Democratic National Convention started on 15 July, 1940, in Chicago . . . and it started out in listless fashion - there wasn't any "We Want FDR" chants from the floor. FDR's powerful supporters started the chant in support of FDR after the nominations were made with the infamous "Sewer Call" (the man in charge of building maintenance was below the floor, with a microphone and a deep sonorous voice; he started the "We Want FDR" chant). FDR wanted to be nominated by acclamation, but a roll call vote took place; FDR easily won the nomination. The delegates felt that they had been manipulated, but they believed that at least they would be able to select FDR's Vice-Presidential candidate; little did they know that FDR was all-in on his SecAg, Henry Wallace (to FDR's right).

FDR absolutely insisted that his Secretary of Agriculture, Henry Wallace, be the Vice-Presidential nominee (he wanted a VP 100% loyal to the New Deal); to the vast majority of delegates, Wallace was viewed as not only far too liberal, but also not qualified. FDR told his most trusted advisor, Harry Hopkins, that if the convention didn't select Wallace as the VP candidate, he would not run for President.

The convention was in an uproar over what delegates considered to be flat-out tyrannical behavior by FDR. The only reason why Wallace was selected as the VP candidate was that Eleanor Roosevelt agreed to speak, not only on behalf of Wallace, but also on behalf of party unity. Wallace narrowly won the VP nomination, but was not allowed to give his acceptance speech, due to fears of a convention revolt. The Democratic National Convention wasn't a coronation for FDR, it was a complete debacle. Polls showed that the Republicans were even with the Democrats by August, 1940.

After the Democratic Convention, Willkie was approached by FDR's representatives, asking him to not attack the pending "Destroyers for Bases" deal with Britain, and Willkie agreed. The deal was the largest and most significant decision yet to aid Great Britain against the Nazis. On 3 September, 1940, FDR announced the "Destroyers for Bases" deal on one of his "Fireside Chats"; as often occurred after a major decision, FDR expected to face defeat. The reality was that the "Destroyers for Bases" deal increased FDR's popularity a great deal, and cost Willkie, who had promised to stay silent.

The convention was in an uproar over what delegates considered to be flat-out tyrannical behavior by FDR. The only reason why Wallace was selected as the VP candidate was that Eleanor Roosevelt agreed to speak, not only on behalf of Wallace, but also on behalf of party unity. Wallace narrowly won the VP nomination, but was not allowed to give his acceptance speech, due to fears of a convention revolt. The Democratic National Convention wasn't a coronation for FDR, it was a complete debacle. Polls showed that the Republicans were even with the Democrats by August, 1940.

After the Democratic Convention, Willkie was approached by FDR's representatives, asking him to not attack the pending "Destroyers for Bases" deal with Britain, and Willkie agreed. The deal was the largest and most significant decision yet to aid Great Britain against the Nazis. On 3 September, 1940, FDR announced the "Destroyers for Bases" deal on one of his "Fireside Chats"; as often occurred after a major decision, FDR expected to face defeat. The reality was that the "Destroyers for Bases" deal increased FDR's popularity a great deal, and cost Willkie, who had promised to stay silent.

The Good News: Britain received 50 destroyers from the U.S. The Bad News: those destroyers were in terrible condition. Despite their poor condition, they proved to be invaluable to Britain's naval strategies of securing their home island. Another result of the deal with Britain was that a shift had occurred in US public opinion: a majority favored overt, direct military assistance to Great Britain.

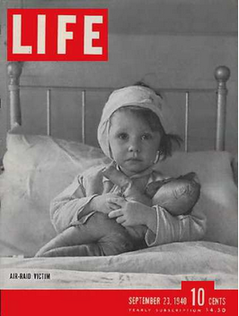

FDR would now be able to push for much more, especially with what would be known as the Lend-Lease Act. During the Battle for Britain

in 1940, U.S. Internationalist media focused on the courage and resilience of the British people to heavy Nazi bombing raids. Life magazine chronicled that experience: the Life magazine cover to the left (an injured British child in a hospital with a stuffed animal) touched the hearts of millions of Americans.

FDR would now be able to push for much more, especially with what would be known as the Lend-Lease Act. During the Battle for Britain

in 1940, U.S. Internationalist media focused on the courage and resilience of the British people to heavy Nazi bombing raids. Life magazine chronicled that experience: the Life magazine cover to the left (an injured British child in a hospital with a stuffed animal) touched the hearts of millions of Americans.

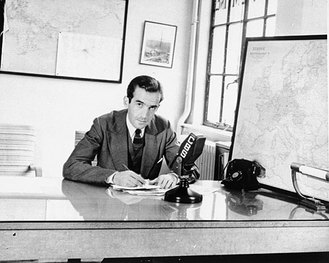

After the Republican and Democratic National Conventions, the journalist that did the most to influence public opinion to provide more direct assistance to Britain was Edward R. Murrow (pictured in CBS HQ in London). His broadcasts from London ("This is London" was his trademark sign-in) was required listening for millions. Morrow was unapologetic in his support for Britain, and in his belief that the Nazis were a threat to not only Europe, but to the U.S.

Adolf Hitler gave America someone to hate, and Britain provided something for Americans to love. By October, during the heat of the general campaign in the Election of 1940, most wanted FDR and the Government to provide direct military support for Britain. But even after defeating Wendell Willkie in November, FDR remained unwilling to provide leadership in that direction . . .

(Below: newsreel footage chronicling Willkie's upset win in Philadelphia in 1940)

Adolf Hitler gave America someone to hate, and Britain provided something for Americans to love. By October, during the heat of the general campaign in the Election of 1940, most wanted FDR and the Government to provide direct military support for Britain. But even after defeating Wendell Willkie in November, FDR remained unwilling to provide leadership in that direction . . .

(Below: newsreel footage chronicling Willkie's upset win in Philadelphia in 1940)