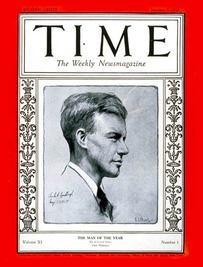

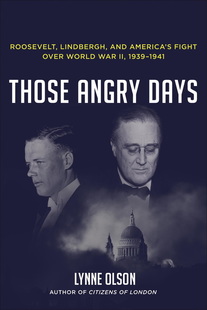

America's Fight Over World War II, 1939 - 1941 (2013)

(four million) showed up for the ticker-tape parade honoring Charles Lindbergh for his miraculous solo flight across the Atlantic. Time Magazine also honored Lindbergh, naming him their first "Man of the Year". Lindbergh toured all 48 states in his beloved "Spirit of St. Louis"; 30 million people were able to see the "Lone Eagle". Shortly thereafter, Lindbergh became a technology advisor to Pan Am and TWA; he was instrumental in creating the first modern airports.

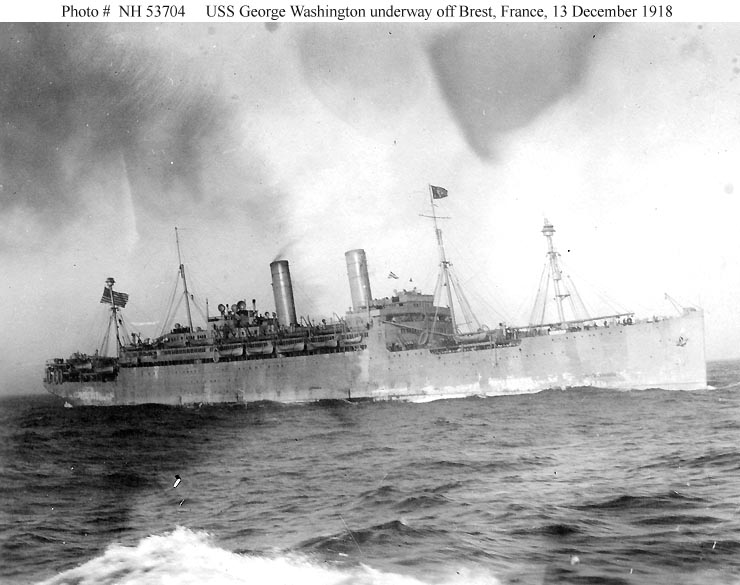

Try as he might, Lindbergh was unable to reclaim his treasured privacy, and restore equilibrium to his life. Wherever he went, he was besieged by the press and adoring citizens. A loner all his life, Lindbergh was unprepared for the trappings of immense fame. As he kept his distance, the public became more hysterical, demanding to see and know more about "Lucky Lindy". After the kidnapping/murder of his first-born son, 2 year-old Charles Jr., a "Paparazzi Attack" occurred on his 2nd-born; it was not too much to state that those events psychologically scarred Lindbergh. As a result, Lindbergh decided to take his family to Europe in December, 1935, in order to escape the insanity that was their life in America.

From 1936 to 1938, Charles Lindbergh, and his almost-as-famous wife, Anne Morrow, lived in England in a secluded estate called "Long Barn" (a friend of the Morrow family owned the estate). There, they were left alone by British citizens and the media. Then, in 1938, the Lindberghs moved to the tiny island of Illiec, off the coast of Brittany (France). That location was even more remote, which suited Lindbergh just fine.

(Below: the British estate nicknamed "Long Barn")

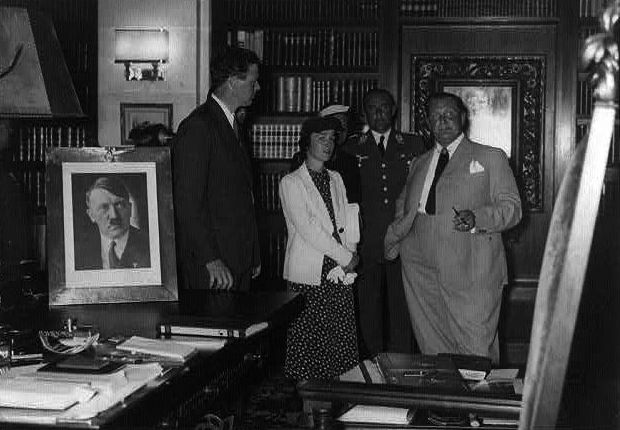

(Below: Hermann Goering giving the Lindberghs a tour of a Nazi government building)

A major result of his visit to Nazi Germany in 1936 was that Lindbergh became convinced that America was on its descent, and that Germany was in its ascendency.

Lindbergh publicly stated that in quantity and quality, no nation(s) could challenge Nazi airpower. But Lindbergh's conclusion was flawed, in that the vaunted Luftwaffe, at that point, was only designed to lead/support troops, not for long-range bombing raids.

Lindbergh's omission of that fact meant that Britain, especially London, was very fearful of bombing runs by Nazi Germany. By publicly bragging about Nazi airpower, Lindbergh was partially responsible for the Appeasement in Munich in 1938.

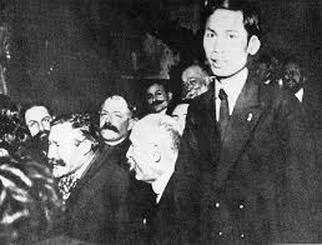

(Below: Lindbergh at a party in Berlin hosted by the Nazis)

was so far removed from the reality of life in Nazi Germany, that he wasn't outraged by the excesses and brutality of the Nazi regime.

In the U.S., news of Lindbergh's visits to Nazi Germany had started to erode his popularity. Erosion of popularity transformed to outright attacks against Lindbergh in the U.S. media when Goering presented Lindbergh with a medal on behalf of the Nazi Government. It was a surprise medal ceremony, and while Lindbergh was flabbergasted (his words), he took the honor in stride. Anne saw the medal much differently, referring to it as "The Albatross", which it would definitely become. The medal ceremony occurred just days before Kristallnacht, and that incidental timing increased the level of outrage in America; not since WW I had there been such anti-German fervor in America. After Kristallnacht, FDR actually recalled the US Ambassador from Berlin.

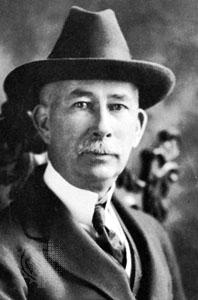

Lindbergh's political myopia explained why he didn't think the thunderstorm that was centered around him was very intense. From 1938-on, the "Medal Incident" was the instrument the media used to bludgeon Lindbergh. And then the federal government started to publicly attack Lindbergh, with FDR's blessing and encouragement. The government figure that ran point attacking Lindbergh was Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes (pictured); in effect, he was FDR's pit bull against Lindbergh. Ickes was already on the warpath against Hitler, so it wasn't too much of a leap at all, politically or personally, for him to start savaging Lindbergh.

The Lindberghs were informed by friends and acquaintances that he was being booed in American theaters when he appeared in newsreels. Anne was greatly shaken by the attacks on her husband; she believed that the media and the government were being beyond-unfair.

As a result, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced the "Line in the Sand": if Nazi Germany invaded Poland, Britain would declare war (France was in agreement). Europe was on the brink of another major war when Lindbergh came back to America. Upon his return, Lindbergh pressed for American neutrality in case of a European War; he believed that America should be the protector of Western Civilization, and the best way to accomplish that goal (in his opinion) was to avoid involvement in the upcoming War in Europe. Not long after Lindbergh's return to the U.S., President Franklin Roosevelt set his sights on trying to destroy the influence and reputation of the most prominent Isolationist in the nation . . . In less than four years, Charles Lindbergh went from the most famous man in America, to the most famous-and-controversial man in America . . . by 1938, that was a title that he shared with FDR . . .