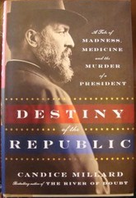

the Murder of a President, 2011

** Dr. Joseph Lister: His antiseptic theory (e.g. sterilizing hands, surgical instruments, germ

theory) was mostly accepted in Europe, but not in America in 1881. The aftermath of the

Garfield assassination led to the general acceptance of his theory and practices in American

medicine

** Dr. Willard Bliss: Garfield's lead doctor was basically a medical dictator; he had total control

to who could access Garfield after the shooting. For almost three months, he treated

Garfield in his way, refusing to listen to other medical opinions. He desperately wanted to

enhance his reputation by being the doctor that healed the president, but his treatment,

even by the standards of 1881, bordered on the cruel and unusual. In the end, his

treatment (and that of a few others before him) led to MASSIVE sepsis (infection), that

was very disturbing to read about, to say the least. He became convinced that the bullet

could only be located on one side of the President's body . . . "Dr. Tunnel-Vision"

** Alexander Graham Bell: Interestingly, the only reason why he became famous for inventing

the telephone was that he was late registering for an "Inventor's Fair", and was located in

an obscure location. About to give up since there had been no foot traffic his way, a group

of very important men walked by on their way out, but one of them recognized Bell, and

the group stopped, and they were amazed by the telephone. Five years later, he wanted to

help find the elusive bullet, and he adapted technology related to the telephone which in

effect, became a kind of "Bullet Detector". This invention worked, but he wasn't able to

find the bullet due to two reasons: a) Bell wasn't told, and didn't bother to find out, that

Garfield was on a metal-spring bed, which was rare in 1881; b) Dr. Bliss absolutely refused

to let him use his invention on the other side of Garfield's body. Had Bell been allowed to

do so, he would have quickly found the bullet.

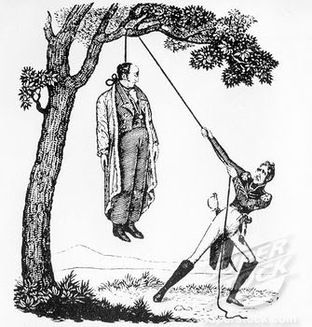

** Charles Guiteau: Garfield's assassin was a certified psychotic; everyone that had any

dealings with him experienced his insanity. Guiteau, in the end, believed he was doing a

great service for the future of America by killing Garfield. He, after at least one failed

attempt, succeeded in shooting Garfield in the back at close range as the President was

heading on vacation in a train station. Guiteau was the only of the four presidential

assassins to receive a fair trial; in the end, the jury refused to acknowledge any aspect of

an insanity defense, and sentenced Guiteau to hang. Guiteau's last words were "Glory,

Glory, Hallelujah."

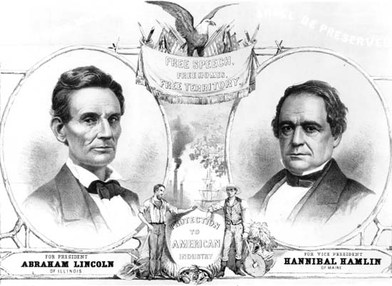

** James Garfield: The President lived for almost three months after he was shot by Guiteau;

given the medical practices of 1881, and the tyrannical Dr. Bliss, he never had a chance

due to the infection that invaded his body. I was struck by how talented and capable he

was politically; it's a shame that we haven't had more presidents with his character,

discipline, and acumen. I think he was the perfect president at the perfect time, which

doesn't happen as much in our history as we would like, or need . . . thanks so much,

CHARLES. During the autopsy, the bullet was found safely encapsulated in scar tissue in

the pancreas. Had nothing been done other than making him comfortable, or had doctors

adhered to Dr. Lister's procedures, he would have survived, and finished his term. The

nation mourned his assassination every bit as much as Lincoln's death twenty years earlier.

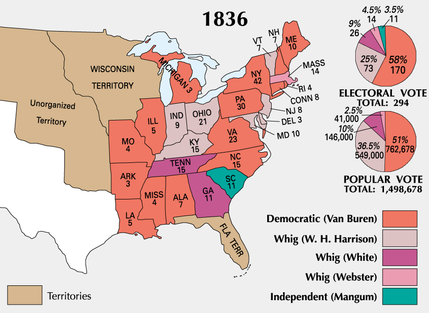

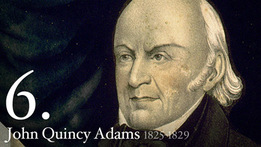

** Roscoe Conkling: The most powerful man in America in 1881 was a U.S. Senator from New

York. The Republican Party was torn apart by a battle between the "Stalwarts" (Conkling,

et al), which supported the "Spoils System" (Cronyism) and the "Half-Breeds" (Garfield, et

al), which supported the "Merit System". According to the "Half-Breeds", it wasn't who you

know that mattered, but whether or not you were competent for the appointed job. This

battle was intense, and almost ripped the Republicans apart. One after-effect of the

assassination was that Conkling was politically out-maneuvered, and actually was convinced

to resign his seat in the Senate. Then, he found out, the state legislature of New York

refused to send him back to Washington; even his right-hand man, Vice-President Chester

Arthur, abandoned him, even after he was sworn in as the 21st President. Garfield must

have been a very inspiring figure, given the complete turnaround of Arthur, who supported

the "Merit System" as president, turning is back on Conkling, the man that politically made

him.

This book was selected as a "One Book, One City" selection for Lincoln in 2011 - I'm glad I had the chance to read it - I learned so much from reading the book - thanks MOM! (But no thanks to you, CHARLES)