Source: Jon Meacham. The Soul of America -

The Battle For Our Better Angels (2018)

The Battle For Our Better Angels (2018)

The “Lost Cause”:

In 1866, Edward Alfred Pollard’s book was published, titled “The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates”. The Lost Cause would thrive, in that Pollard declared that the great enemy of the South was the federal government in Washington, D.C. It was a bold move to continue the fight in the face of catastrophic losses from the Civil War (to give one an idea of how much suffering Southern states endured as a result of the Civil War, in 1866 the state of Mississippi allotted 20% of its state budget for wooden limbs).

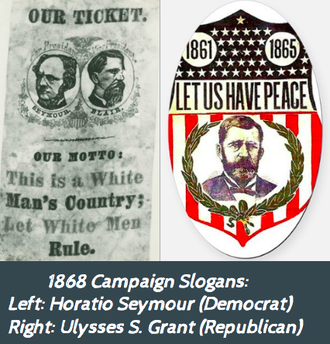

“The Lost Cause Regained” was published in 1868, and Pollard argued that the question in play no longer concerned slavery, but white supremacy. The “true hope” of the South, to Pollard, was to successfully reassert state rights, and the rejection of federal rule became a holy war for the vast majority of Southern whites. In effect, Southern whites dug in for the longest of sieges. Former Confederate general Jubal Early also helped grow the Lost Cause by focusing on, and celebrating, Southern heroes of the Civil War. First up for Early was General Robert E. Lee, and praise for Lee reached the stratosphere after his death in 1870; the Lost Cause now had a narrative complete with heroes.

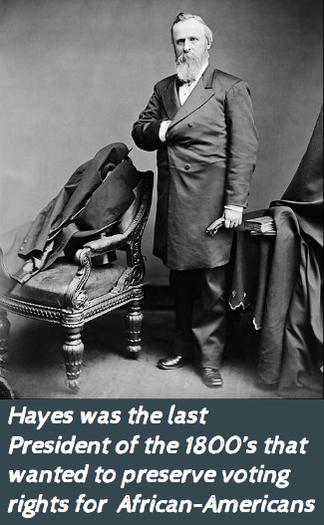

The Lost Cause held that the Union won the Civil War due to brute force, which meant that Southern whites cold live in the past as well as the present, in that old times would never be forgotten . . . and that the South would eventually prevail and restore their landscape to what it was before the Civil War. For Southern whites, winning the “2nd Civil War” (Reconstruction) would be defined by the extent the South could subjugate African-Americans; after 1877, the nadir in US History for African-Americans truly began.

In 1866, Edward Alfred Pollard’s book was published, titled “The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates”. The Lost Cause would thrive, in that Pollard declared that the great enemy of the South was the federal government in Washington, D.C. It was a bold move to continue the fight in the face of catastrophic losses from the Civil War (to give one an idea of how much suffering Southern states endured as a result of the Civil War, in 1866 the state of Mississippi allotted 20% of its state budget for wooden limbs).

“The Lost Cause Regained” was published in 1868, and Pollard argued that the question in play no longer concerned slavery, but white supremacy. The “true hope” of the South, to Pollard, was to successfully reassert state rights, and the rejection of federal rule became a holy war for the vast majority of Southern whites. In effect, Southern whites dug in for the longest of sieges. Former Confederate general Jubal Early also helped grow the Lost Cause by focusing on, and celebrating, Southern heroes of the Civil War. First up for Early was General Robert E. Lee, and praise for Lee reached the stratosphere after his death in 1870; the Lost Cause now had a narrative complete with heroes.

The Lost Cause held that the Union won the Civil War due to brute force, which meant that Southern whites cold live in the past as well as the present, in that old times would never be forgotten . . . and that the South would eventually prevail and restore their landscape to what it was before the Civil War. For Southern whites, winning the “2nd Civil War” (Reconstruction) would be defined by the extent the South could subjugate African-Americans; after 1877, the nadir in US History for African-Americans truly began.

The 2nd KKK, Part I:

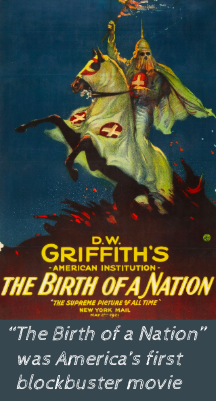

While President Woodrow Wilson made generous comments concerning the movie “The Birth of a Nation”, after large protests in northeastern cities such as Boston and Philadelphia, Wilson publicly distanced himself from America’s first blockbuster movie. It was in large part to the initial success of the movie that the 2nd Ku Klux Klan started in Georgia in late-November 1915. By 1924, the 2nd KKK had a significant presence in each of the 48 states. Unease over increasing crime, worries about anarchists, fear of immigrants flooding into the US from Southern and Eastern Europe led to millions of American joining the ranks of the 2nd KKK. By 1917, the fear of the spread of Communism stoked those fears even further, and the “hate list” of the 2nd KKK included Catholics and Jews in addition to African-Americans.

While the national landscape changed to a more urban America after World War I, the 2nd KKK promised racial solidarity and cultural certitude. The popularity of the 2nd KKK was due at least in part to the many changes in America that occurred during and after the Great War. Therefore, it was not a surprise that the Palmer Raids were not only conducted but supported (“100% Americanism” was the watch-phrase). It became a virtual requirement to paint one’s political enemies with the brush of Bolshevism. President Wilson was inactive during the Palmer Raids, so it took other checks, such as the courts, to rein in the 1st Red Scare.

By the mid-1920s, the 2nd KKK’s membership was over 2 million, perhaps between 3 and 6 million. The 2nd KKK was a huge influence in the Democratic National Convention of 1924 in Madison Square Garden. The 2nd KKK was powerful enough to at least cause hesitation, if not outright fear, among Democratic politicians. The 2nd KKK also fought against an officially proposed anti-Klan plank in the convention’s platform. The 2nd KKK denied Al Smith (NY) the nomination (as did the pro-Prohibition forces under the leadership of Wayne Wheeler), but they were unable to get their candidate, SecTreas William McAdoo, nominated. In the end, it took 103 ballots to nominate John W. Davis. During August 1925, 30,000 Klansmen (perhaps as many as 50k) took part in a march on the National Mall.

While President Woodrow Wilson made generous comments concerning the movie “The Birth of a Nation”, after large protests in northeastern cities such as Boston and Philadelphia, Wilson publicly distanced himself from America’s first blockbuster movie. It was in large part to the initial success of the movie that the 2nd Ku Klux Klan started in Georgia in late-November 1915. By 1924, the 2nd KKK had a significant presence in each of the 48 states. Unease over increasing crime, worries about anarchists, fear of immigrants flooding into the US from Southern and Eastern Europe led to millions of American joining the ranks of the 2nd KKK. By 1917, the fear of the spread of Communism stoked those fears even further, and the “hate list” of the 2nd KKK included Catholics and Jews in addition to African-Americans.

While the national landscape changed to a more urban America after World War I, the 2nd KKK promised racial solidarity and cultural certitude. The popularity of the 2nd KKK was due at least in part to the many changes in America that occurred during and after the Great War. Therefore, it was not a surprise that the Palmer Raids were not only conducted but supported (“100% Americanism” was the watch-phrase). It became a virtual requirement to paint one’s political enemies with the brush of Bolshevism. President Wilson was inactive during the Palmer Raids, so it took other checks, such as the courts, to rein in the 1st Red Scare.

By the mid-1920s, the 2nd KKK’s membership was over 2 million, perhaps between 3 and 6 million. The 2nd KKK was a huge influence in the Democratic National Convention of 1924 in Madison Square Garden. The 2nd KKK was powerful enough to at least cause hesitation, if not outright fear, among Democratic politicians. The 2nd KKK also fought against an officially proposed anti-Klan plank in the convention’s platform. The 2nd KKK denied Al Smith (NY) the nomination (as did the pro-Prohibition forces under the leadership of Wayne Wheeler), but they were unable to get their candidate, SecTreas William McAdoo, nominated. In the end, it took 103 ballots to nominate John W. Davis. During August 1925, 30,000 Klansmen (perhaps as many as 50k) took part in a march on the National Mall.

The 2nd KKK, Part II:

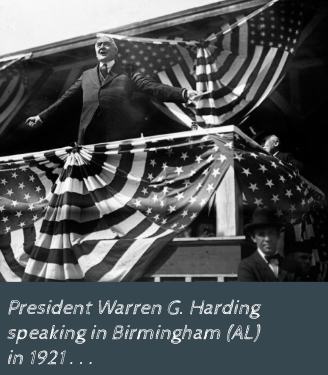

There were prominent voices that spoke out against the 2nd KKK as early as 1921, when President Warren Harding went to Birmingham (AL) in 1921 and spoke out against the 2nd KKK and its extra-legal vigilantism. Harding was even more direct in 1923 when he dedicated a statue of Alexander Hamilton in front of the US Treasury building, referring to the 2nd KKK as a conspiracy, not a fraternity. The 2nd KKK responded by spreading unsubstantiated rumors that Harding had African-American ancestry (in 2015, DNA tests disproved the rumor). After Harding’s death in 1923, the 2nd KKK spread the rumor that Harding had secretly joined its ranks while in office.

President Coolidge wanted to focus attention on the increasing national unity, balancing the federal budget, while also denying the 2nd KKK publicity and attention . . . the less said about the Klan, the better. Coolidge knew enough about history to know that the 2nd KKK would burn itself out, which is exactly what occurred. But Coolidge’s silence led to many African-Americans questioning whether the Republicans were the right party for them. On 9 August 1924, Coolidge made a public statement condemning the 2nd Klu Klux Klan. By 1928, the power and influence of the 2nd KKK (the “Mussolini of America”) had started to decline. That same year, the Supreme Court upheld a New York law that required the 2nd KKK to file membership lists with state authorities.

There were prominent voices that spoke out against the 2nd KKK as early as 1921, when President Warren Harding went to Birmingham (AL) in 1921 and spoke out against the 2nd KKK and its extra-legal vigilantism. Harding was even more direct in 1923 when he dedicated a statue of Alexander Hamilton in front of the US Treasury building, referring to the 2nd KKK as a conspiracy, not a fraternity. The 2nd KKK responded by spreading unsubstantiated rumors that Harding had African-American ancestry (in 2015, DNA tests disproved the rumor). After Harding’s death in 1923, the 2nd KKK spread the rumor that Harding had secretly joined its ranks while in office.

President Coolidge wanted to focus attention on the increasing national unity, balancing the federal budget, while also denying the 2nd KKK publicity and attention . . . the less said about the Klan, the better. Coolidge knew enough about history to know that the 2nd KKK would burn itself out, which is exactly what occurred. But Coolidge’s silence led to many African-Americans questioning whether the Republicans were the right party for them. On 9 August 1924, Coolidge made a public statement condemning the 2nd Klu Klux Klan. By 1928, the power and influence of the 2nd KKK (the “Mussolini of America”) had started to decline. That same year, the Supreme Court upheld a New York law that required the 2nd KKK to file membership lists with state authorities.

FDR and the Great Depression, Part I:

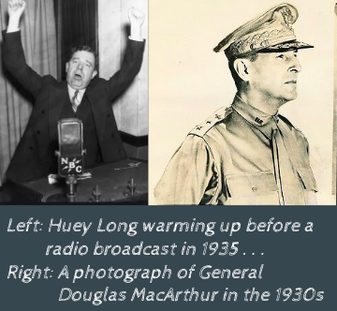

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in a trilogy he wrote on FDR that was published between 1957-60, referred to the 1920s and the 1930s as the “Crisis of the Old Order”; would the nation save itself or go the route of totalitarianism or communism. During the Summer of 1932, FDR told an advisor that the two most dangerous men in the US were Huey Long (from the Left) and General Douglas MacArthur (from the Right). The loudest cheer that FDR received during his 1st Inaugural Address on 4 March 1933 was his statement that he may need to assume extended wartime powers.

Some of the powerful elites from Wall Street and Big Business tried to enlist former Marine General Smedley Butler to raise an army and march it into Washington, D.C. to remove FDR as President, beyond-fearful of FDR’s reforms. Butler not only flat-out told those that wanted to depose FDR that he would raise an army greater than theirs to combat them, and then Butler informed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover about the conspiracy. Congress held secret hearings in 1934 where Butler told of what he knew, and on 21 November 1934, the NY Times published an article exposing the plot. Given the economic, political, and social atmosphere in the US at the time, that coup could very well have at least been attempted.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in a trilogy he wrote on FDR that was published between 1957-60, referred to the 1920s and the 1930s as the “Crisis of the Old Order”; would the nation save itself or go the route of totalitarianism or communism. During the Summer of 1932, FDR told an advisor that the two most dangerous men in the US were Huey Long (from the Left) and General Douglas MacArthur (from the Right). The loudest cheer that FDR received during his 1st Inaugural Address on 4 March 1933 was his statement that he may need to assume extended wartime powers.

Some of the powerful elites from Wall Street and Big Business tried to enlist former Marine General Smedley Butler to raise an army and march it into Washington, D.C. to remove FDR as President, beyond-fearful of FDR’s reforms. Butler not only flat-out told those that wanted to depose FDR that he would raise an army greater than theirs to combat them, and then Butler informed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover about the conspiracy. Congress held secret hearings in 1934 where Butler told of what he knew, and on 21 November 1934, the NY Times published an article exposing the plot. Given the economic, political, and social atmosphere in the US at the time, that coup could very well have at least been attempted.

FDR and the Great Depression, Part II:

FDR’s main job, especially before World War II, was to make sure to keep those from the extreme Left and Right from destroying America’s democratic and capitalist systems. FDR was scored and ridiculed in the beginning of his Presidency by millions of Americans, but by the end of his 12+ years as President, he was a hero to the nation. Among the reasons why include FDR overcoming his disability, as well as his incurable (public) optimism. FDR was often exasperating, but in the long run he didn’t let down the nation in terms of dealing with the “big things”.

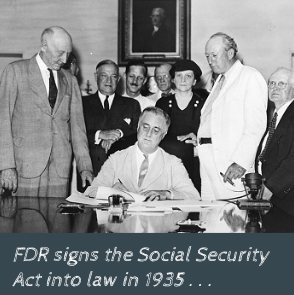

During the Second New Deal in 1935, FDR largely blunted Huey Long’s plan of redistributing wealth by getting the Social Security, Wagner, and Works Progress Acts through Congress. FDR was key in establishing a bridge from the perilous past to the far more secure future. Even so, while FDR spoke out against the lynchings in the North and South, he didn’t want to promote the anti-lynching bill, fearful that Southern Democratic Senators in key committee chairmanship positions would impede the New Deal. During the perilous past from 1900 through 1933, there were 3500+ lynchings, but only 67 indictments and 12 convictions, and in this situation, FDR was not a bridge to a more secure future for African-Americans.

FDR’s main job, especially before World War II, was to make sure to keep those from the extreme Left and Right from destroying America’s democratic and capitalist systems. FDR was scored and ridiculed in the beginning of his Presidency by millions of Americans, but by the end of his 12+ years as President, he was a hero to the nation. Among the reasons why include FDR overcoming his disability, as well as his incurable (public) optimism. FDR was often exasperating, but in the long run he didn’t let down the nation in terms of dealing with the “big things”.

During the Second New Deal in 1935, FDR largely blunted Huey Long’s plan of redistributing wealth by getting the Social Security, Wagner, and Works Progress Acts through Congress. FDR was key in establishing a bridge from the perilous past to the far more secure future. Even so, while FDR spoke out against the lynchings in the North and South, he didn’t want to promote the anti-lynching bill, fearful that Southern Democratic Senators in key committee chairmanship positions would impede the New Deal. During the perilous past from 1900 through 1933, there were 3500+ lynchings, but only 67 indictments and 12 convictions, and in this situation, FDR was not a bridge to a more secure future for African-Americans.

Senator Joseph McCarthy, Part I:

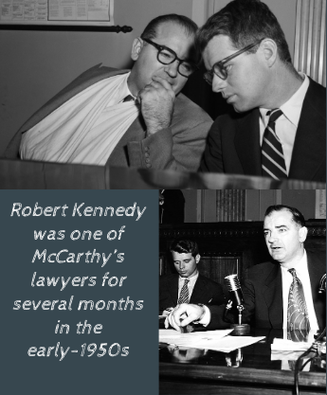

Historically, Americans approve of the government’s role when they benefit, and howl when others are on the receiving end whey they are not. That dichotomy was exacerbated when the programs from the New deal and World War II became permanent government fixtures. As prosperity and infrastructure improved, the “Fear Factor” concerning foreign influence and subversion, especially communism, remained. To Senator Joseph McCarthy (WI), politics wasn’t about the substantive, but the sensational. McCarthy, ever the opportunist and attention-seeker, was only interested in pursuing fame and gaining influence, and fanning the flames of the Second Red Scare was his ticket to achieving those goals. Starting in 1950, McCarthy basically became the Huey Long of the North.

When McCarthy spoke, everything was dramatic, contentious, and dangerous, and McCarthy absolutely reveled in the media reports that portrayed him as a brave warrior against the Communist Menace. Television offered McCarthy an ever-expanding reach, and soon millions of Americans believed that McCarthy was an American hero. Far too many journalists during the early-to-mid 1950s focused on the traditional method of reporting, which meant rehashing McCarthy’s statements instead of verifying the validity of the Senator’s statements. For the publications that dared to venture towards finding out the real facts behind McCarthy’s assertions that there were hundreds of communists in the federal government, McCarthy’s public vitriol was fierce.

Historically, Americans approve of the government’s role when they benefit, and howl when others are on the receiving end whey they are not. That dichotomy was exacerbated when the programs from the New deal and World War II became permanent government fixtures. As prosperity and infrastructure improved, the “Fear Factor” concerning foreign influence and subversion, especially communism, remained. To Senator Joseph McCarthy (WI), politics wasn’t about the substantive, but the sensational. McCarthy, ever the opportunist and attention-seeker, was only interested in pursuing fame and gaining influence, and fanning the flames of the Second Red Scare was his ticket to achieving those goals. Starting in 1950, McCarthy basically became the Huey Long of the North.

When McCarthy spoke, everything was dramatic, contentious, and dangerous, and McCarthy absolutely reveled in the media reports that portrayed him as a brave warrior against the Communist Menace. Television offered McCarthy an ever-expanding reach, and soon millions of Americans believed that McCarthy was an American hero. Far too many journalists during the early-to-mid 1950s focused on the traditional method of reporting, which meant rehashing McCarthy’s statements instead of verifying the validity of the Senator’s statements. For the publications that dared to venture towards finding out the real facts behind McCarthy’s assertions that there were hundreds of communists in the federal government, McCarthy’s public vitriol was fierce.

Senator Joseph McCarthy, Part II:

During the general campaign on 3 October 1952, Republican Presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower had a chance to publicly defend former General George C. Marshall from McCarthy’s accusations that he enabled communists to operate under his nose in State Department in the Truman administration . . . Ike didn’t defend Marshall. Unlike Truman who openly denounced McCarthy, Ike was patient and mostly quiet; like Coolidge and the 2nd KKK, Ike believed that denying attention to McCarthy would help minimize his impact.

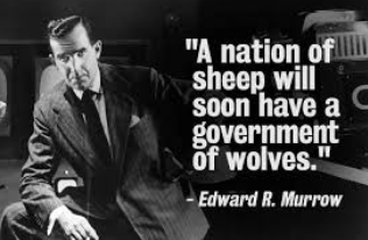

So it wasn’t the President that went after McCarthy, but the legendary television journalist

Edward R. Murrow on his CBS news show “See It Now” on 9 March 1954. Murrow, in a sorrowful manner, attacked McCarthy, lamenting that disloyalty had become confused with honest dissent. Murrow closed by saying it wasn’t McCarthy’s fault, in that the Senator was merely tapping into the national feelings, but Murrow also stated that the McCarthy’s actions/words were giving far too much advantage to America’s enemies.

The end for McCarthy came just months after Murrow’s broadcast with the Army-McCarthy Hearings. On the nationally televised hearings, McCarthy repeatedly came off poorly to millions of viewers, and his image was no longer that of a brave warrior against communism. Even so, McCarthy’s base supporters remained fiercely loyal, but any threat McCarthy posed evaporated later in 1954 when his fellow Senators censured him, which was mostly due to McCarthy’s reckless methods that violated the traditions of the Senate. The Senate resolution that condemned McCarthy passed by a vote of 67 - 22, with 22 Republican Senators joining the vote for censure. Television largely created McCarthy, and television largely took him down . . . but millions of Americans remained fearful of internal subversion well into the early-1960s.

During the general campaign on 3 October 1952, Republican Presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower had a chance to publicly defend former General George C. Marshall from McCarthy’s accusations that he enabled communists to operate under his nose in State Department in the Truman administration . . . Ike didn’t defend Marshall. Unlike Truman who openly denounced McCarthy, Ike was patient and mostly quiet; like Coolidge and the 2nd KKK, Ike believed that denying attention to McCarthy would help minimize his impact.

So it wasn’t the President that went after McCarthy, but the legendary television journalist

Edward R. Murrow on his CBS news show “See It Now” on 9 March 1954. Murrow, in a sorrowful manner, attacked McCarthy, lamenting that disloyalty had become confused with honest dissent. Murrow closed by saying it wasn’t McCarthy’s fault, in that the Senator was merely tapping into the national feelings, but Murrow also stated that the McCarthy’s actions/words were giving far too much advantage to America’s enemies.

The end for McCarthy came just months after Murrow’s broadcast with the Army-McCarthy Hearings. On the nationally televised hearings, McCarthy repeatedly came off poorly to millions of viewers, and his image was no longer that of a brave warrior against communism. Even so, McCarthy’s base supporters remained fiercely loyal, but any threat McCarthy posed evaporated later in 1954 when his fellow Senators censured him, which was mostly due to McCarthy’s reckless methods that violated the traditions of the Senate. The Senate resolution that condemned McCarthy passed by a vote of 67 - 22, with 22 Republican Senators joining the vote for censure. Television largely created McCarthy, and television largely took him down . . . but millions of Americans remained fearful of internal subversion well into the early-1960s.