Source: Stuart E. Eizenstat. President Carter - The White House Years (2018)

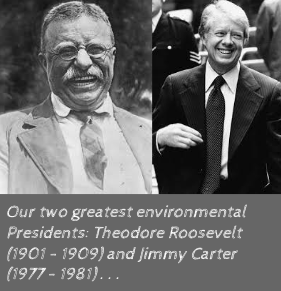

If measured by acreages preserved and policies enacted, Jimmy Carter was an even greater environmental President than Theodore Roosevelt. It was astonishing how much Carter achieved in terms of the environment in his single term in office. As always, Carter took on entrenched interests and was oblivious to the political costs. Carter was able to do all this by giving industries flexibility to meet new environmental standards using a so-called bubble called “Cap and Trade”, which benefited companies that met/exceeded the new policies.

Carter’s efforts on the environment occurred at the same time as the environmentalism movement was gaining steam; also in play was Carter’s focus on health and safety, and he was strongly influenced by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). On 22 July 1969, chemical discharges in the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire and burned, which in essence was the spark the environmental movement needed, and the first

Earth Day occurred on 22 April 1970 (which was modeled after the “Teach-Ins” of the Vietnam Era). Carter understood that the key to gaining public support to further protect the environment was gaining the support of America’s middle class . . . what Carter didn’t understand right away was that powerful vested interests would be obstacles in the way of his environmental goals.

Carter’s efforts on the environment occurred at the same time as the environmentalism movement was gaining steam; also in play was Carter’s focus on health and safety, and he was strongly influenced by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). On 22 July 1969, chemical discharges in the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire and burned, which in essence was the spark the environmental movement needed, and the first

Earth Day occurred on 22 April 1970 (which was modeled after the “Teach-Ins” of the Vietnam Era). Carter understood that the key to gaining public support to further protect the environment was gaining the support of America’s middle class . . . what Carter didn’t understand right away was that powerful vested interests would be obstacles in the way of his environmental goals.

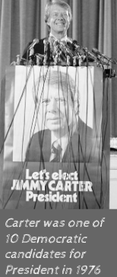

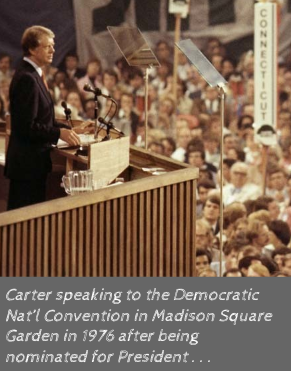

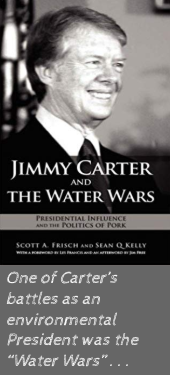

During his campaign for President in 1976, Carter made it very clear that he was opposed to the construction of unnecessary dams as well as unnecessary channeling of streams and rivers; Carter’s stand was clear during what became known as the “Water Wars”. Carter stance put him in opposition to the Army Corps of Engineers, who by then had become cozy with Congress and often sugar-coated and distorted the benefits of damming compared to the actual financial/environmental costs; environmental damage was not part of the calculated/predicted costs of the Corps of Engineers. Once construction started on a Corps project, it could not be stopped.

Carter was about to discover that it had been much easier to stop the damming of the Flint River in Georgia when he was governor that to stop the hundreds of proposed water projects backed by powerful members in Congress. Carter had the initials advantage as his Presidency started in 1977 in that the Democrats had huge majorities in both houses (292 - 143 in the House, and a filibuster-proof 62 - 38 in the Senate). But Carter dumped a ton of major bills on that friendly (and soon to be, in their opinion, overworked) Congress in a short period of time, and very soon Carter’s political capital started to dwindle; politically during the Water Wars, Carter lost in every conceivable way due to his plan of attack.

Carter was about to discover that it had been much easier to stop the damming of the Flint River in Georgia when he was governor that to stop the hundreds of proposed water projects backed by powerful members in Congress. Carter had the initials advantage as his Presidency started in 1977 in that the Democrats had huge majorities in both houses (292 - 143 in the House, and a filibuster-proof 62 - 38 in the Senate). But Carter dumped a ton of major bills on that friendly (and soon to be, in their opinion, overworked) Congress in a short period of time, and very soon Carter’s political capital started to dwindle; politically during the Water Wars, Carter lost in every conceivable way due to his plan of attack.

On 9 December 1976 as President-Elect in a meeting, Carter wanted an energy proposal in 90 days plus he wanted to find ways to cut back on government spending for water resources which meant there was no time to “test the waters” in Congress. Leaks soon occurred about Carter’s water goals, and Congress and the media turned the situation into a deluge. Powerful members of the Old Guard in the House considered water projects to be their province, not the President’s.

Carter ignored sage advice from among others Vice-President Walter Mondale, and Carter also refused to focus on a few of the most egregious water projects, choosing instead to stand on principle. At best, Carter viewed that option (called Option B) as nothing more than a shot across to bow which wouldn’t accomplish what he wanted. The bitterness of Carter’s initial approach, as with the energy bill, was to be the lasting memory instead of the eventual accomplishments. The initial perception was that Carter had declared war on the Western states, even though there were just as many pending/proposed water projects east of the Mississippi River that were at risk. Carter wanted to end 35 water projects at once instead of focusing on a few in Option B.

Carter ignored sage advice from among others Vice-President Walter Mondale, and Carter also refused to focus on a few of the most egregious water projects, choosing instead to stand on principle. At best, Carter viewed that option (called Option B) as nothing more than a shot across to bow which wouldn’t accomplish what he wanted. The bitterness of Carter’s initial approach, as with the energy bill, was to be the lasting memory instead of the eventual accomplishments. The initial perception was that Carter had declared war on the Western states, even though there were just as many pending/proposed water projects east of the Mississippi River that were at risk. Carter wanted to end 35 water projects at once instead of focusing on a few in Option B.

On 17 February 1977 Carter told those assembled that he wanted a total stop to 35 targeted water projects, not just denying government funding. Carter was advised by virtually every heavy hitter at the meeting, including Mondale, to go with Option B, but Carter stubbornly refused and focused on the death penalty for the 35 water projects. Carter saw doing so as a matter of principle, and the politics be damned. The only softening of Carter’s stance was that the number could be less than 35, but he would select the projects that needed to be stopped in their tracks, which reduced the number to 19 targeted water projects.

But somebody at the meeting leaked Carter’s goal and the reduced number, and the firestorm started, fed mostly by Carter’s insistence that his strategy remain secret until the official announcement, which in effect denied Congress forewarning and the ability to provide feedback to Carter. Had Carter applied his cost-benefit analysis to the political costs of his approach compared to the relatively minor fiscal savings of shutting down 19 targeted water projects, he would have realized that he would be the biggest loser . . . but he did not and Carter lost politically, big-time. As that firestorm around the 19 water projects intensified, Carter scrambled to develop a strategy, and just like with his energy plan (which was occurring at the same time), the kind of meeting that Carter should have had in the very beginning involving others with vested interests outside of his administration took place far too late.

But somebody at the meeting leaked Carter’s goal and the reduced number, and the firestorm started, fed mostly by Carter’s insistence that his strategy remain secret until the official announcement, which in effect denied Congress forewarning and the ability to provide feedback to Carter. Had Carter applied his cost-benefit analysis to the political costs of his approach compared to the relatively minor fiscal savings of shutting down 19 targeted water projects, he would have realized that he would be the biggest loser . . . but he did not and Carter lost politically, big-time. As that firestorm around the 19 water projects intensified, Carter scrambled to develop a strategy, and just like with his energy plan (which was occurring at the same time), the kind of meeting that Carter should have had in the very beginning involving others with vested interests outside of his administration took place far too late.

Out of sheer political necessity, Carter was forced to go to Option B as a strategy to notify the public of what he was trying to accomplish and to pick a public fight with Congress . . . and Carter got what he wanted. More than one staffer wrote that Carter had barreled ahead with considering the political consequences. It did not help matters that Carter wanted to keep a water project alive in Georgia that had the name of the late Senator Richard Russell attached.

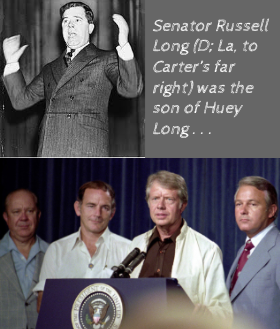

During March 1977, Carter announced that 337 water projects had been reviewed, and 305 had been approved for future funding. That “Hit List” sent shock waves through Congress; in no way did members of both houses believe that local/regional water projects were in the province of the President. Congressman Jim Wright (D; Tx) and Senator Russell Long (D; La) were apoplectic, and even Senator Edmund Muskie (D; Me), an environmental politician, was all-in protecting a water project in his state. In terms of procedure, members of Congress were right since all the targeted water projects had been properly vetted on multiple fronts.

During March 1977, Carter announced that 337 water projects had been reviewed, and 305 had been approved for future funding. That “Hit List” sent shock waves through Congress; in no way did members of both houses believe that local/regional water projects were in the province of the President. Congressman Jim Wright (D; Tx) and Senator Russell Long (D; La) were apoplectic, and even Senator Edmund Muskie (D; Me), an environmental politician, was all-in protecting a water project in his state. In terms of procedure, members of Congress were right since all the targeted water projects had been properly vetted on multiple fronts.

Mondale found himself needing to hold his tongue with his former colleagues in the Senate on the behavior and strategies of the relative political amateurs in the inexperienced Carter administration. Carter eventually (grudgingly) agreed to exempt cuts from already-approved water projects although he firmly believed it was a waste of government spending. In the midst of both the energy and water debacles, there was the reality that Carter had refused to appoint a Chief of Staff; that person would have been invaluable in crafting proper strategies and procedures for the new President.

Adding to the mounting problems was that Carter, at least early in his Presidency, stubbornly refused to act upon, or sometimes even listen to, good sound political advice from his Circle of Trust. Carter’s view of what should be accomplished as President was in moral terms, and those that didn’t share that view were seen as part of the problem, even corrupt. Carter had jumped into the water with alligators and he as bound-and-determined in the early months of his Presidency to show that he could prevail against the Establishment of his own party . . .

Adding to the mounting problems was that Carter, at least early in his Presidency, stubbornly refused to act upon, or sometimes even listen to, good sound political advice from his Circle of Trust. Carter’s view of what should be accomplished as President was in moral terms, and those that didn’t share that view were seen as part of the problem, even corrupt. Carter had jumped into the water with alligators and he as bound-and-determined in the early months of his Presidency to show that he could prevail against the Establishment of his own party . . .