Source: John A. Farrell. Richard Nixon - The Life (2017)

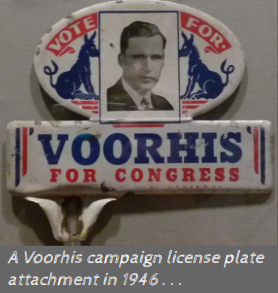

In August 1946, Voorhis left DC for California, but while driving through Utah with his family, he had a nasty attack of hemorrhoids, and after emergency surgery, he had a bad reaction to the anesthesia. For weeks afterwards, Voorhis battled headaches, nausea, and other various unpleasant effects that kept him from campaigning. When Voorhis was finally in well enough to campaign, he was hit hard by Nixon’s charges that he had sided with Communists against his constituents.

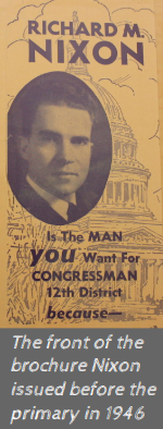

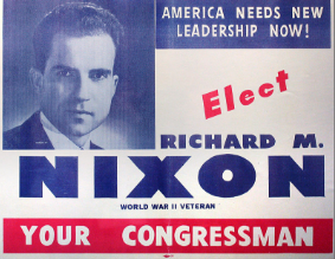

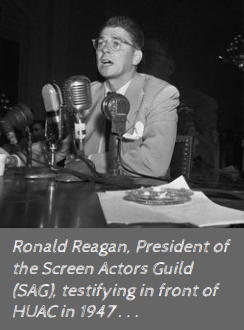

In 1946, the Director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, told the American Legion Convention in San Francisco that 100,000 Communist subversives were active in America. HUAC had been very active and public in their efforts to expose subversives, and soon enough Hollywood was dragged into to fracas as well, with among others Ronald Reagan eventually testifying in front of HUAC (as President of the Screen Actors Guild). NIxon and other Republican candidates simply framed their campaigns as “Communism vs. Republicanism”; the fear factor was growing, and just the accusation of being soft on Communism was a political killer. Nixon’s campaign never flat-out called Voorhis a Communist, but politically-speaking, in the eyes of many voters, Voorhis was guilty by indirect accusation.

In 1946, the Director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, told the American Legion Convention in San Francisco that 100,000 Communist subversives were active in America. HUAC had been very active and public in their efforts to expose subversives, and soon enough Hollywood was dragged into to fracas as well, with among others Ronald Reagan eventually testifying in front of HUAC (as President of the Screen Actors Guild). NIxon and other Republican candidates simply framed their campaigns as “Communism vs. Republicanism”; the fear factor was growing, and just the accusation of being soft on Communism was a political killer. Nixon’s campaign never flat-out called Voorhis a Communist, but politically-speaking, in the eyes of many voters, Voorhis was guilty by indirect accusation.

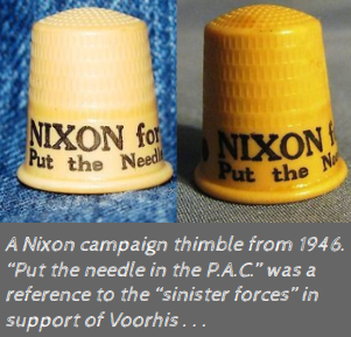

Nixon bent over backwards to link Voorhis to an obscure endorsement he received from a minor left wing group of radicals in Los Angeles, which was loosely affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Voorhis ordered his campaign to steer clear of any group related to the CIO, which meant that Voorhis had to woo some labor group and shun others, which split a major voting bloc that was in his favor.

Nixon wanted credit for exposing Voorhis, and the only way that could occur is if he won the election. Nixon ignored the reality that the link between Voorhis and the minor radical group was practically non-existent, and Nixon portrayed Voorhis as a stooge for the Communists. Soon, Nixon claimed that Voorhis towed the Communist Party Line, and many voters believed Nixon. It wasn’t until 11 September 1946 that Voorhis took out full page ads to refute Nixon’s claims, demanding that evidence be presented.

Nixon wanted credit for exposing Voorhis, and the only way that could occur is if he won the election. Nixon ignored the reality that the link between Voorhis and the minor radical group was practically non-existent, and Nixon portrayed Voorhis as a stooge for the Communists. Soon, Nixon claimed that Voorhis towed the Communist Party Line, and many voters believed Nixon. It wasn’t until 11 September 1946 that Voorhis took out full page ads to refute Nixon’s claims, demanding that evidence be presented.

Two days later, the “proper proof” was produced at a debate in Pasadena during the first debate. Neither candidate really wanted to have a debate, but neither wanted to look worthless-and-weak by refusing to debate. Nixon engaged in shenanigans right away during the first debate, appearing on stage late to disrupt Voorhis as he was speaking. As the debate progressed, Voorhis demanded proof, and NIxon, acting the part to perfection, strode across the stage to Voorhis and gave him a document. That document was supposedly a list of preferred candidates by the radical group, and Voorhis’ name was on the list. A very surprised Voorhis fumbled his response, and Nixon enjoyed the loud applause from his supporters in the gallery; Nixon felt the same rush a lawyer did when he nailed a closing argument in front of a jury.

It soon became apparent to Voorhis after the debate that Nixon had crushed him, and the Voorhis campaign never recovered. The debate started voters in the district to seriously discuss the candidates and the campaign, which was exactly what Nixon needed. Also, the Republican Party in California finally realized that Nixon was for real and could win, and 70% of Nixon’s campaign money in the last phase of the campaign came from the CA Republicans. Another factor in Nixon’s corner was that the Los Angeles Times, due initially to Kyle Palmer’s insistence, fully endorsed Nixon.

It soon became apparent to Voorhis after the debate that Nixon had crushed him, and the Voorhis campaign never recovered. The debate started voters in the district to seriously discuss the candidates and the campaign, which was exactly what Nixon needed. Also, the Republican Party in California finally realized that Nixon was for real and could win, and 70% of Nixon’s campaign money in the last phase of the campaign came from the CA Republicans. Another factor in Nixon’s corner was that the Los Angeles Times, due initially to Kyle Palmer’s insistence, fully endorsed Nixon.

It wasn’t just the CA Republican Party’s cash infusion that helped the Nixon campaign down the final stretch, but significant commercial interests added their support in the last weeks of the campaign. Businesses that had been reluctant to back a losing Republican candidate now jumped at the chance to back a winner. The only opening for Voorhis against Nixon was to ask for the sources of his his campaign contributions. Nixon officially reported spending $17,774, but in reality, the figure was around $40k ($500k in 2017 dollars). No one in the campaign had an exact handle on the total of contributions since so much money had been given to the campaign in such a short period of time. Nixon knew that as long as he was vague in thanking his large donors (he promised them thanks and attention later), he could minimize total on the official campaign financial report.

There were four more debates, and Voorhis was slaughtered in every one; the crowds grew larger in order to see the political bloodletting. Nixon enjoyed mentioning as often as he could that Voorhis was a former member of the Socialist Party, and it sure didn’t help Voorhis when Nixon stated that Radio Moscow had endorsed the CIO’s list of candidates. Another obstacle for Voorhis was that Nixon’s campaign was very well organized and focused, where Voorhis’ campaign was a wreck, which in part meant that Nixon was able to speak to groups of voters that had never heard the name of Voorhis. A cheesy campaign strategy by Nixon’s staff right before the election worked this way: when the phone rang, and the person that answered said “Vote Nixon for Congress”, and the caller was from the Nixon campaign, that person’s name was put in the running to win a toaster. Voorhis yearned for a genteel political discussion in public, but Nixon conducted an aggressive and rugged campaign, and in essence Voorhis brought a banana to a knife fight.

There were four more debates, and Voorhis was slaughtered in every one; the crowds grew larger in order to see the political bloodletting. Nixon enjoyed mentioning as often as he could that Voorhis was a former member of the Socialist Party, and it sure didn’t help Voorhis when Nixon stated that Radio Moscow had endorsed the CIO’s list of candidates. Another obstacle for Voorhis was that Nixon’s campaign was very well organized and focused, where Voorhis’ campaign was a wreck, which in part meant that Nixon was able to speak to groups of voters that had never heard the name of Voorhis. A cheesy campaign strategy by Nixon’s staff right before the election worked this way: when the phone rang, and the person that answered said “Vote Nixon for Congress”, and the caller was from the Nixon campaign, that person’s name was put in the running to win a toaster. Voorhis yearned for a genteel political discussion in public, but Nixon conducted an aggressive and rugged campaign, and in essence Voorhis brought a banana to a knife fight.

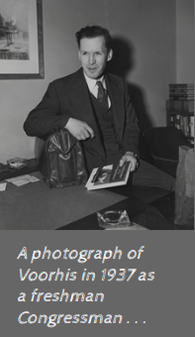

The Congressional Elections of 1946 showed that the New Deal Coalition was crumbling, in that the Republicans took control of both houses for the first time since 1930. Early during Election Day, Voorhis knew he was defeated. Nixon garnered 56% of the vote, sweeping to victory in every part of the 12th District, even Voorhis’ area. A destroyed Voorhis fled politics, which infuriated the California Democratic Party who thought he should focus on a rematch with Nixon in 1948. But Voorhis in defeat understood that the 12th District was now a Republican stronghold. By his own admission, Voorhis stated that his gentleman’s style of campaigning simply didn’t match up with Nixon’s brawling strategies/tactics. Even so, Voorhis privately remained furious at Nixon for sinking so low in order to win.

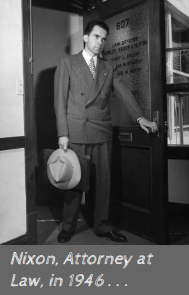

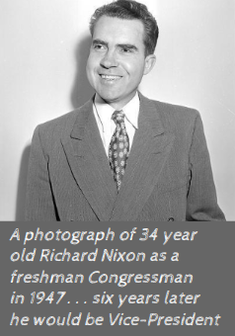

In winning the seat to Congress from California’s 12th District, Nixon showed qualities that would be seen again and again: audacity, resourcefulness, resilience, hard work, and knowing what voters wanted to hear. But the dark side of Nixon showed itself as well: awkwardness, deep resentment, expediency-over-purpose, chronic insecurity, and the use of smears against an opponent. In just four years, Nixon would be elected to the US Senate from California, and two years after that, Eisenhower tabbed Nixon to be his Vice-President. In just six years, Nixon had gone from obscurity to the second-highest elected office in the nation in what was perhaps the fastest rise to political prominence in US History.

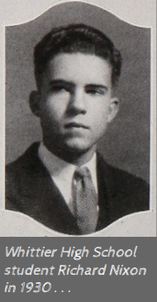

Addendum: Richard Nixon's years before he received the letter from Herman Perry

In winning the seat to Congress from California’s 12th District, Nixon showed qualities that would be seen again and again: audacity, resourcefulness, resilience, hard work, and knowing what voters wanted to hear. But the dark side of Nixon showed itself as well: awkwardness, deep resentment, expediency-over-purpose, chronic insecurity, and the use of smears against an opponent. In just four years, Nixon would be elected to the US Senate from California, and two years after that, Eisenhower tabbed Nixon to be his Vice-President. In just six years, Nixon had gone from obscurity to the second-highest elected office in the nation in what was perhaps the fastest rise to political prominence in US History.

Addendum: Richard Nixon's years before he received the letter from Herman Perry