Source: David Halberstam. The Powers That Be (2012)

By 1965, television had, among other aspects of the Vietnam War, magnified that it was impossible for US soldiers to differentiate between friend and foe in South Vietnam. On top of that, television also magnified the duration of the war, in that in TV years 1965 - 1968 was an eternity. The Vietnam War played out on TV in US homes, and it played too long, which made it seem to millions of Americans that US involvement in SE Asia was a never-ending enterprise, and by early-1968, Walter Cronkite came to that conclusion.

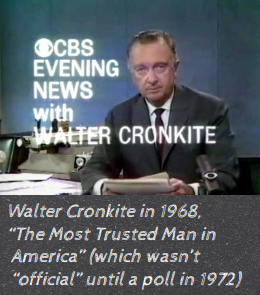

Walter Cronkite, the CBS Evening News anchorman, was a great weathervane to see the changing attitudes in American unfold concerning the Vietnam War. Initially, Cronkite supported US involvement, but in early-1968, “The Most Trusted Man in America” came out against the government’s decisions/policies in Vietnam in respectable opposition, disassociating himself with the war. In the early years of the war, Cronkite used his massive credibility to lend assistance to the government and the military, viewing the the conflict in SE Asia as necessary. Rare was the American that saw the Vietnam War for what it truly was, a War of National Liberation (as was the American Revolution), so it was predictable that Cronkite agreed with the powers-that-be that the US should not appease the North Vietnamese Communists, and that North Vietnam should be contained. Cronkite, like the rest of America, had given his trust to those in power.

Cronkite, who by 1965 had reached the pinnacle of his profession, figured that those in the top positions in the government and military knew what they were doing (as he did), and he took their word for the progress of the war. By his own admission, Cronkite, when he went to Saigon for the first time in 1965, was a George Kennan Containment Man, following the conventional wisdom of the Cold War Era.

Walter Cronkite, the CBS Evening News anchorman, was a great weathervane to see the changing attitudes in American unfold concerning the Vietnam War. Initially, Cronkite supported US involvement, but in early-1968, “The Most Trusted Man in America” came out against the government’s decisions/policies in Vietnam in respectable opposition, disassociating himself with the war. In the early years of the war, Cronkite used his massive credibility to lend assistance to the government and the military, viewing the the conflict in SE Asia as necessary. Rare was the American that saw the Vietnam War for what it truly was, a War of National Liberation (as was the American Revolution), so it was predictable that Cronkite agreed with the powers-that-be that the US should not appease the North Vietnamese Communists, and that North Vietnam should be contained. Cronkite, like the rest of America, had given his trust to those in power.

Cronkite, who by 1965 had reached the pinnacle of his profession, figured that those in the top positions in the government and military knew what they were doing (as he did), and he took their word for the progress of the war. By his own admission, Cronkite, when he went to Saigon for the first time in 1965, was a George Kennan Containment Man, following the conventional wisdom of the Cold War Era.

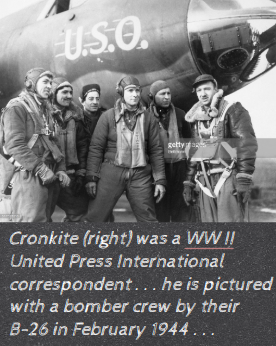

In 1965, Cronkite didn’t like the brashness of the young correspondents in Saigon, or their skepticism and pessimism about the war; Cronkite gave the government and military men the benefit of the doubt in 1965. Morley Safer, the CBS correspondent in Saigon, tried to educate Cronkite and connect him with talented correspondents, but Cronkite’s perspective was anchored in World War II, and that meant he trusted the powers-that-be. In fact, the government/military used Cronkite’s immense influence and credibility for their own ends, and even against Cronkite himself. Cronkite had been warned by friends and colleagues that he shouldn’t go to Saigon in 1965 since he would be used as a tool to promote government/military decision making in SE Asia, but Cronkite could not resist going. Cronkite felt a strong pull during WW II to go to Britain and cover the war, and that same feeling pulled him to South Vietnam.

However, one thing did bother Cronkite in Saigon in 1965: he was repeatedly told that the war would be short and small, yet he witnessed massive military construction projects going on which flat-out countered that claim. On his return to the CBS Evening News anchor desk, Cronkite did feature enough reports from Safer and John Laurence (the other prominent CBS correspondent) where the White House referred to CBS as the “Communist Broadcasting Network”. Eventually Cronkite, like much of the nation, became frustrated at the endlessness of the war, and Cronkite increasingly came to doubt the credibility of the men in charge of the war.

However, one thing did bother Cronkite in Saigon in 1965: he was repeatedly told that the war would be short and small, yet he witnessed massive military construction projects going on which flat-out countered that claim. On his return to the CBS Evening News anchor desk, Cronkite did feature enough reports from Safer and John Laurence (the other prominent CBS correspondent) where the White House referred to CBS as the “Communist Broadcasting Network”. Eventually Cronkite, like much of the nation, became frustrated at the endlessness of the war, and Cronkite increasingly came to doubt the credibility of the men in charge of the war.

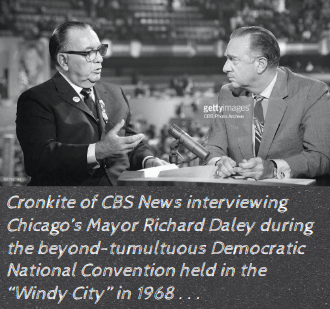

Cronkite was great at leading and being led at the same time, so when the national mood towards the Vietnam War shifted, Cronkite was at the tip of that developing tidal wave. In 1967, it was announced that Harry Reasoner of CBS was heading to Saigon, and right away Reasoner got a call from LBJ to meet. LBJ outlined what he expected of Reasoner in terms of coverage in South Vietnam, and the President asked Reasoner if he had any questions. Reason asked if he could talk with the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, and that conversation occurred almost immediately. Reasoner left for Saigon feeling that LBJ and McNamara were depressed and cornered men.

By 1967, the word “stalemate” started to appear more-and-more in the world of journalism concerning Vietnam. As 1968 opened, LBJ was on the defensive, with television no longer an asset to the President, and increasingly, TV featured more-and-more of the anti-war perspective. Before 1968 the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) preferred nighttime raids, and they vanished before dawn, knowing that daylight was an additional enemy which led to more casualties. That strategy also meant that TV had a hard time documenting the actual war between the VC/NVA and the US and the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN).

By 1967, the word “stalemate” started to appear more-and-more in the world of journalism concerning Vietnam. As 1968 opened, LBJ was on the defensive, with television no longer an asset to the President, and increasingly, TV featured more-and-more of the anti-war perspective. Before 1968 the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) preferred nighttime raids, and they vanished before dawn, knowing that daylight was an additional enemy which led to more casualties. That strategy also meant that TV had a hard time documenting the actual war between the VC/NVA and the US and the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN).

That changed with the Tet Offensive in January/February 1968. For the first time, the VC/NVA fought during the day, day after day, and TV captured it all . . . and day after day the credibility of LBJ and the White House decreased. The first results of the Tet Offensive was that the President’s Propaganda Machine was badly damaged, and that Cronkite’s perspective of the war changed. Also, Tet shook up the WW II orientation of the powerful figures in the media, which meant that the media would no longer automatically believe LBJ.

During Tet, Cronkite decided to again go to Saigon, knowing full well that he was stepping out of his role as anchorman into an editorial role, and that his career may change for the worse. At a military press conference, General William Westmoreland (who was surprised when he heard Cronkite was present) stated that Tet was exactly what the US had wanted all along, that if the VC/NVA would fight a traditional war, the superpower would crush them. To Cronkite, it was an Orwellian experience, seeing the Ministry of Truth in Charge of Lying (No one in the military understood that Vietnam wasn’t a “Real Estate War” like WW II).

Cronkite had trouble even landing in South Vietnam due to the fighting associated with Tet, so he was unable to go to Khe Sanh and instead went to Hue, where the NVA had in effect surrounded the Marines. Cronkite was truly an embedded wartime correspondent again: with his own eyes, he witnessed the gap between the reality of the war and the false/ignorant claims of the US government/military. Cronkite flew out from Hue accompanied by the body bags of 12 dead US soldiers.

During Tet, Cronkite decided to again go to Saigon, knowing full well that he was stepping out of his role as anchorman into an editorial role, and that his career may change for the worse. At a military press conference, General William Westmoreland (who was surprised when he heard Cronkite was present) stated that Tet was exactly what the US had wanted all along, that if the VC/NVA would fight a traditional war, the superpower would crush them. To Cronkite, it was an Orwellian experience, seeing the Ministry of Truth in Charge of Lying (No one in the military understood that Vietnam wasn’t a “Real Estate War” like WW II).

Cronkite had trouble even landing in South Vietnam due to the fighting associated with Tet, so he was unable to go to Khe Sanh and instead went to Hue, where the NVA had in effect surrounded the Marines. Cronkite was truly an embedded wartime correspondent again: with his own eyes, he witnessed the gap between the reality of the war and the false/ignorant claims of the US government/military. Cronkite flew out from Hue accompanied by the body bags of 12 dead US soldiers.

Cronkite then meet with General Creighton Abrams (who was a friend, as was soon to replace Westmoreland) who confirmed Cronkite’s doubts of the war. Next Cronkite flew to Saigon to meet with CBS correspondents, and he talked to Laurence in particular. Cronkite transformed from a neutral anchorman to a personal journalist as a result of the Tet Offensive. Cronkite briefed his superiors on what he was going to do, and they gave him, if not their blessing, then permission to proceed, knowing that Cronkite’s televised opinion could be a severe blow to the reputation of CBS News. Cronkite didn’t want to go down that road, but the decision making of those in power plus the changing political landscape left him in essence with no choice but to air his views.

Cronkite wrote a thirty minute broadcast special, and his conclusion was that it was time for the US to get out of Vietnam; he was ready to make that statement as was much of the nation to hear him. Cronkite changed the balance in that it was the first time in US History a war had been declared over by an anchorman. Cronkite was one of the reasons why LBJ announced on 31 March 1968 that he would not run again for President (the biggest reason was that RFK had entered the Democratic primaries, and he flat-out refused to lose to the man he hated more than any other . . . LBJ’s main fears were failure and humiliation).

LBJ still liked Cronkite, believing that he was different from what he considered to be the unpatriotic renegades in the media. Cronkite was perhaps the only major journalist that LBJ respected and admired, knowing that Cronkite cared deeply about the welfare of the nation. LBJ realized that he had lost the “Center”, and the Cronkite must know things concerning the war that he, as President, didn’t know.

Also: Cronkite's Top Ten TV Moments . . .

Cronkite wrote a thirty minute broadcast special, and his conclusion was that it was time for the US to get out of Vietnam; he was ready to make that statement as was much of the nation to hear him. Cronkite changed the balance in that it was the first time in US History a war had been declared over by an anchorman. Cronkite was one of the reasons why LBJ announced on 31 March 1968 that he would not run again for President (the biggest reason was that RFK had entered the Democratic primaries, and he flat-out refused to lose to the man he hated more than any other . . . LBJ’s main fears were failure and humiliation).

LBJ still liked Cronkite, believing that he was different from what he considered to be the unpatriotic renegades in the media. Cronkite was perhaps the only major journalist that LBJ respected and admired, knowing that Cronkite cared deeply about the welfare of the nation. LBJ realized that he had lost the “Center”, and the Cronkite must know things concerning the war that he, as President, didn’t know.

Also: Cronkite's Top Ten TV Moments . . .