Source: David Halberstam. The Powers That Be (2012)

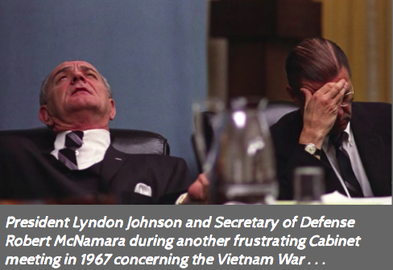

The power balance in the US had changed by the 1960s, in that the President dominated, and Congress was at best a secondary sideline player by comparison, and one of the main reasons was television. TV had become a weapon of the President, helping him define events on his own terms, especially if an issue/event was still ongoing . . . but that worked against President Lyndon Johnson during the Vietnam War and President Richard Nixon during the Watergate Scandal. The President could set things in motion, but as both LBJ and Nixon discovered, they couldn’t control subsequent events.

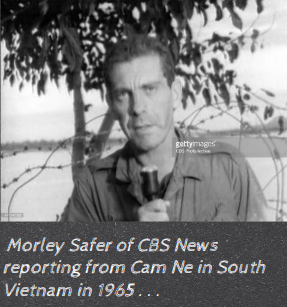

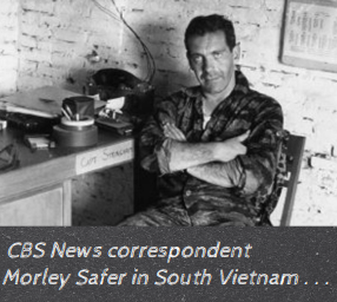

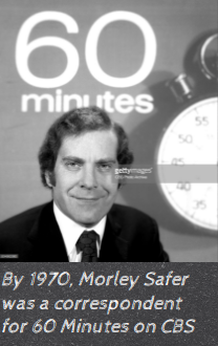

During the 1960s, events could sweep past politicians since television reached everyone, not just the Elites, and sometimes events overwhelmed both the government and protesters. LBJ set things in motion with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, but he couldn’t control what occurred afterwards in 1965; and LBJ couldn’t control Morley Safer of CBS News in South Vietnam. Safer (35 years old) was an experienced foreign correspondent that was familiar with global military and political conflicts.

During the 1960s, events could sweep past politicians since television reached everyone, not just the Elites, and sometimes events overwhelmed both the government and protesters. LBJ set things in motion with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, but he couldn’t control what occurred afterwards in 1965; and LBJ couldn’t control Morley Safer of CBS News in South Vietnam. Safer (35 years old) was an experienced foreign correspondent that was familiar with global military and political conflicts.

Safer was new at CBS and single, therefore relatively expendable in the eyes of the executives at CBS News, and he was sent to Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City today) for a six month assignment. Safer believed he was sent to Vietnam because his bosses didn’t believe that the war would last very long. What struck Safer the most when he arrived in Saigon was the innocence and naivete of the US military officials in terms of the reality of what was happening around them. A transition was occurring when Safer arrived in that the US attitude towards the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam) had changed. In the eyes of the US military, by 1965 the ARVN was no longer the “little tiger” that could, in that many South Vietnamese soldiers cut and ran at the first opportunity during combat. As a result, General William Westmoreland wanted more US troops in Vietnam; the only real candor coming from the US military concerning Vietnam centered around how poorly the ARVN acquitted itself in combat. In July 1965, LBJ announced that he would send 125,000 troops to South Vietnam.

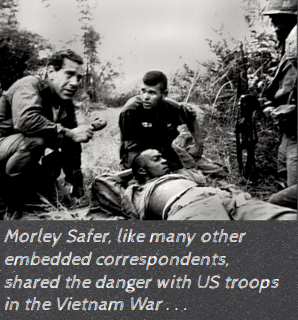

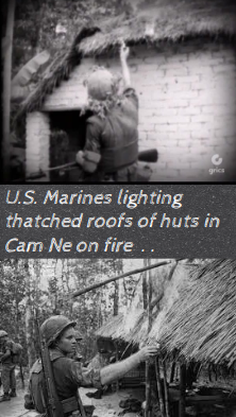

In August 1965, Safer went to Da Nang, which was the staging area for the US Marines in South Vietnam, for the main reason that he hadn’t recently covered the Marines. Safer was known to have “combat luck” by his fellow reporters, which meant that Safer often witnessed and reported on combat; he also had the luck to survive to narrate what he had witnessed. Safer was asked by the Marines if he wanted to accompany them to Cam Ne, which was in actuality a complex of villages. On the way there, Safer was told that the village would be leveled since they had taken fire from the Viet Cong at that location.

In August 1965, Safer went to Da Nang, which was the staging area for the US Marines in South Vietnam, for the main reason that he hadn’t recently covered the Marines. Safer was known to have “combat luck” by his fellow reporters, which meant that Safer often witnessed and reported on combat; he also had the luck to survive to narrate what he had witnessed. Safer was asked by the Marines if he wanted to accompany them to Cam Ne, which was in actuality a complex of villages. On the way there, Safer was told that the village would be leveled since they had taken fire from the Viet Cong at that location.

The real reason for the march on Cam Ne was that the province chief wanted Cam Ne punished for not paying taxes, and the Marines were the punishers . . . such was the Vietnam War. Three Marines were wounded on the way to Cam Ne. Safer noted that it was due to friendly fire; the Marines were enraged, and they took the village without any resistance.

Safer was worried that he hadn’t portrayed the reality of Cam Ne is it really was; Cam Ne was far uglier than Safer reported. Marines used hand grenades and flamethrowers where villagers were cowering in fear. The only real hero on the US side was Ha Thuc Can, a South Vietnamese cameraman that worked for CBS. Can was fluent in Vietnamese, French, and English, and he stopped further carnage by arguing with the Marines about what they were doing, which saved the lives of at least some of the villagers.

Safer asked the Marine commander why he didn’t bring along an interpreter, and the lieutenant stated that he didn’t need one. Can saved at least a dozen people, and as a reward, the man in charge of public relations for the Defense Department tried to make CBS fire him, saying that using a South Vietnamese cameraman was a sure sign of “alien influence”.

(Below: part of a Vietnam documentary focusing on Safer and Cam Ne)

Safer was worried that he hadn’t portrayed the reality of Cam Ne is it really was; Cam Ne was far uglier than Safer reported. Marines used hand grenades and flamethrowers where villagers were cowering in fear. The only real hero on the US side was Ha Thuc Can, a South Vietnamese cameraman that worked for CBS. Can was fluent in Vietnamese, French, and English, and he stopped further carnage by arguing with the Marines about what they were doing, which saved the lives of at least some of the villagers.

Safer asked the Marine commander why he didn’t bring along an interpreter, and the lieutenant stated that he didn’t need one. Can saved at least a dozen people, and as a reward, the man in charge of public relations for the Defense Department tried to make CBS fire him, saying that using a South Vietnamese cameraman was a sure sign of “alien influence”.

(Below: part of a Vietnam documentary focusing on Safer and Cam Ne)

Safer, a seasoned veteran foreign correspondent was shocked at what he had witnessed at Cam Ne. Safer was used to seeing French cruelty in Algeria, but here he was seeing American soldiers commit the same kind of atrocities, and Americans didn’t do those things . . . but Safer saw that American soldiers could commit atrocities. Safer filed his story on the spot, and his only regret was that he didn’t take more time to be more accurate and specific in terms of the cruelty involved.

When Safer’s report come to CBS, there was an immediate understanding of the power and danger as far as broadcasting the story. CBS News executives watched the film of the Marines burning village huts (but they didn’t see the footage of the worst of the atrocities), and after checking with Safer to make sure the facts were correct, the decision was made to broadcast the story CBS fielded many phone calls from angry citizens that cried foul, since it was obvious that US soldiers never have, and never did, anything like that . . . ever.

The next day, LBJ called one of his closest allies that was an upper-level executive at CBS and read him the riot act over the phone (among the phrases was, “you just s&%# on the American Flag”). LBJ was certain that Safer was a Communist, and how could CBS put someone like that in the field. LBJ ordered a thorough background check on Safer. Safer was originally from Canada, so that meant LBJ needed the cooperation of the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police); it was discovered that Safer was beyond above-board in terms of any loyalty or security risks. LBJ was sure nonetheless that Safer had somehow convinced the Marines to do what they did at Cam Ne, which was just a hint of LBJ’s excessive paranoia to come in the succeeding years. Despite intense pressure from President Johnson, CBS stood by Safer, and broadcast his story.

When Safer’s report come to CBS, there was an immediate understanding of the power and danger as far as broadcasting the story. CBS News executives watched the film of the Marines burning village huts (but they didn’t see the footage of the worst of the atrocities), and after checking with Safer to make sure the facts were correct, the decision was made to broadcast the story CBS fielded many phone calls from angry citizens that cried foul, since it was obvious that US soldiers never have, and never did, anything like that . . . ever.

The next day, LBJ called one of his closest allies that was an upper-level executive at CBS and read him the riot act over the phone (among the phrases was, “you just s&%# on the American Flag”). LBJ was certain that Safer was a Communist, and how could CBS put someone like that in the field. LBJ ordered a thorough background check on Safer. Safer was originally from Canada, so that meant LBJ needed the cooperation of the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police); it was discovered that Safer was beyond above-board in terms of any loyalty or security risks. LBJ was sure nonetheless that Safer had somehow convinced the Marines to do what they did at Cam Ne, which was just a hint of LBJ’s excessive paranoia to come in the succeeding years. Despite intense pressure from President Johnson, CBS stood by Safer, and broadcast his story.

Safer’s report marked the end of an era, and end to an innocence that cut into the inner soul of the US. Cam Ne was like a live grenade detonated in the living rooms of American citizens. Watching US soldiers (“Our Boys”) conduct themselves like the enemy had done in previous wars shattered the myth that had been crafted by countless Westerns, as well as both world wars . . . the myth that the US acted and behaved better than everyone else in terms of waging war.

Safer helped legitimize accurate reporting in Vietnam by other TV correspondents, with all resolving to capture what they witnessed on film. From that moment on in 1965, there was a greater receptiveness to the darker news coming out of Vietnam. For an increasing number of Americans, there was this sense that the War in Vietnam wasn’t going right, despite what the government and military stated.

Safer helped legitimize accurate reporting in Vietnam by other TV correspondents, with all resolving to capture what they witnessed on film. From that moment on in 1965, there was a greater receptiveness to the darker news coming out of Vietnam. For an increasing number of Americans, there was this sense that the War in Vietnam wasn’t going right, despite what the government and military stated.